Stanley Kubrick didn't just film movies; he conducted psychological experiments on his audience. If you sit down to read the full metal jacket movie script, you aren't just looking at dialogue and stage directions. You’re looking at a document that evolved, mutated, and eventually broke every rule of traditional three-act structure. Most war movies have a hero who learns a lesson. This script has a protagonist who loses his soul in the first half and spends the second half trying to find a reason to keep it lost.

It’s messy. It's mean. Honestly, it’s one of the most polarizing pieces of writing in cinema history.

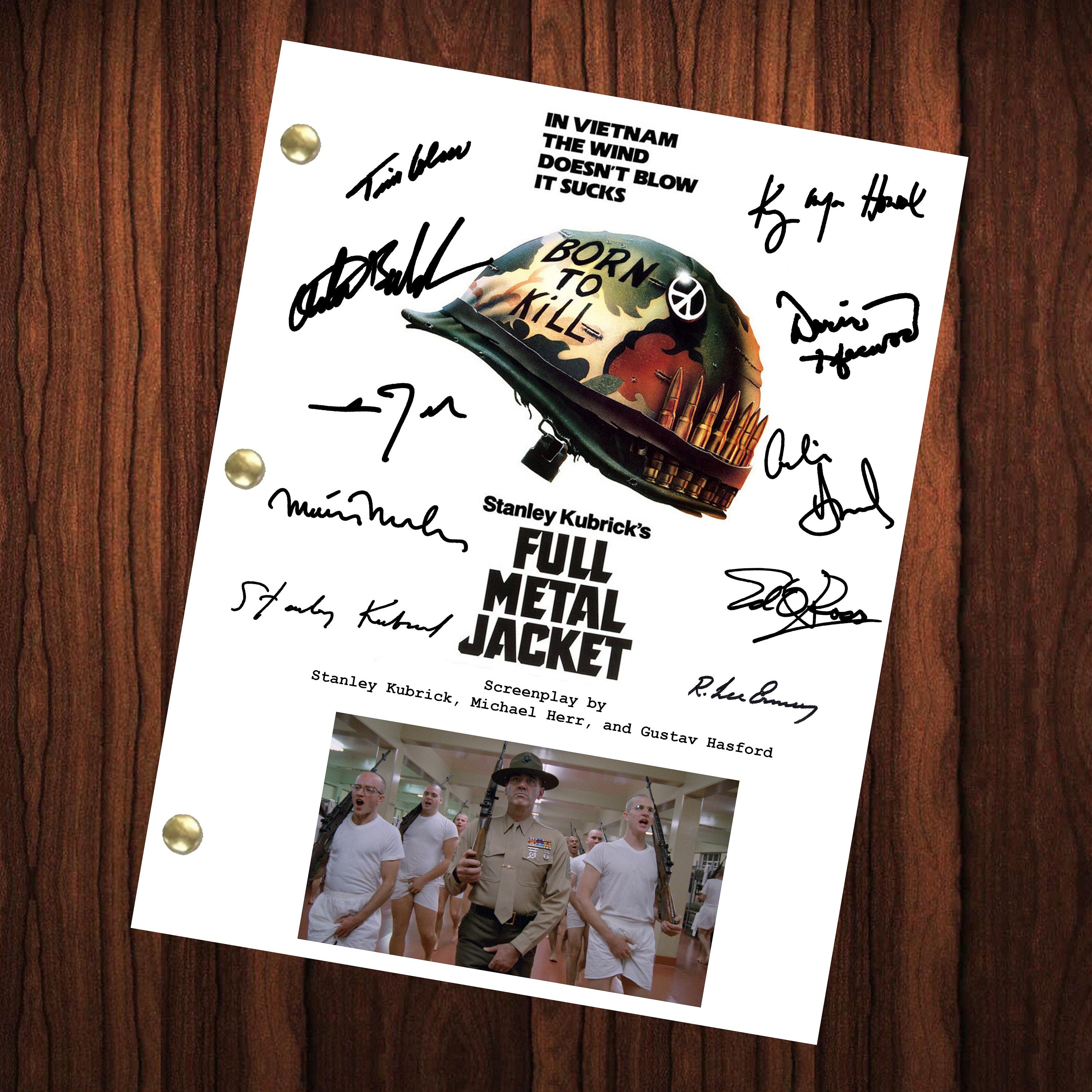

People always talk about the drill sergeant. R. Lee Ermey is the face of the film, but the writing behind his vitriol is where the real magic happened. The screenplay, credited to Kubrick, Michael Herr, and Gustav Hasford, was based on Hasford’s novel The Short-Timers. But if you compare the book to the final full metal jacket movie script, you’ll see where Kubrick’s obsession with "the duality of man" took over.

The Script That Wasn't Really a Script

Kubrick worked differently than anyone else in Hollywood. Usually, a script is a blueprint. For Full Metal Jacket, the script was more like a suggestion that kept changing until the cameras stopped rolling.

Michael Herr, who wrote the legendary Vietnam memoir Dispatches, was brought in because Kubrick wanted that "grunt" authenticity. Herr once noted that Kubrick was terrified of making a "conventional" war movie. He didn't want Platoon. He didn't want Apocalypse Now. He wanted something colder. Something more clinical.

The first half of the script—the Parris Island sequence—is basically a pressure cooker. It’s repetitive. It’s meant to be. The dialogue is designed to strip away the individuality of the characters until they are nothing but "maggots." This wasn't just for the actors; it was for the reader. When you look at the page, the blocks of text for Gunnery Sergeant Hartman are massive. They dominate the white space. It feels suffocating just to read it.

👉 See also: Who is the Scented with Love Cast? Meet the Faces of the 2022 Rom-Com

Then, R. Lee Ermey happened.

Ermey wasn't even supposed to be in the movie. He was a technical advisor. But he sent Kubrick a tape of himself yelling insults for fifteen minutes straight without repeating himself once, even while people were throwing oranges at him. Kubrick was so floored that he incorporated Ermey's improvisations directly into the shooting script. This is rare for a Kubrick film. Usually, he’s a control freak about every syllable. But with the full metal jacket movie script, he realized that real-world experience trumped his own writing. About 50% of Hartman's dialogue in the final film was Ermey’s own "cadence" and insults brought from his time as a real-world Drill Instructor.

Breaking the Two-Act Wall

One of the biggest complaints people have about the movie is that it feels like two different films stitched together. You’ve got the boot camp, and then you’ve got Vietnam.

In a standard screenplay, your "Inciting Incident" happens around page 15. In the full metal jacket movie script, the biggest turning point—the death of Pyle and Hartman—happens right at the midpoint. It’s a total structural middle finger to Hollywood norms.

Why did they do it?

Because the script is about the "Born to Kill" mentality. The first half shows how the machine is built. The second half shows the machine failing in the field. If you read the screenplay carefully, the character of Joker (played by Matthew Modine) is the only thread holding it together. He’s the "smart-aleck" who thinks he’s above the system, but the script slowly reveals that he’s just as much a part of the carnage as anyone else.

The second half, set during the Tet Offensive, is where Michael Herr’s influence shines. The dialogue becomes more cynical and detached. There’s a specific scene where the soldiers are being interviewed by a news crew. In the script, this is written to highlight the absurdity of the war. They aren't talking about freedom or democracy. They’re talking about movies, pussy, and the fact that they’re just there because they were told to be.

The Peace Sign and the Helmet

"I think I was trying to suggest something about the duality of man, sir. The Jungian thing."

That line from Joker is the heart of the full metal jacket movie script. He wears a peace sign button on his lapel and has "Born to Kill" written on his helmet. It sounds like a cliché now because it’s been parodied a thousand times, but in 1987, that was a radical way to frame a protagonist.

Kubrick and Hasford fought a lot during the writing process. Hasford was a cynical veteran who wanted the script to be even darker than it was. Kubrick, surprisingly, wanted a bit more of a "narrative" flow. The tension between those two perspectives created a script that feels both surreal and grounded.

The sniper sequence at the end is a masterclass in tension on the page. In the script, the sniper is a phantom. The dialogue is sparse. It’s just "8-ball" and "Cowboy" getting picked apart while the rest of the squad watches in horror. The revelation that the sniper is a young girl wasn't just a shock tactic; it was written to force the characters (and the audience) to confront the "enemy" as a human being for the first time in the entire film.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Writing

Most fans think the movie is an anti-war statement. It kinda is, but the script is actually more interested in the process of dehumanization than the politics of Vietnam.

The writing doesn't judge Hartman. It doesn't even really judge the sniper. It just presents them.

If you're studying the full metal jacket movie script for your own writing, pay attention to the "cadence." The characters don't talk like people in a drama. They talk in rhythms. The marching chants, the insults, the radio chatter—it’s all rhythmic. It creates a sense of inevitability. Like a clock ticking toward a bomb.

Another thing: the script is surprisingly funny. It’s a pitch-black, gallows humor that only people in high-stress environments really get. When Joker jokes about "the great state of Texas" or "the Mickey Mouse Club," it isn't just filler. It’s a survival mechanism written into the DNA of the dialogue.

Key Takeaways for Screenwriters and Fans

Reading this script is a lesson in how to break rules effectively. You don't need a three-act structure if your theme is strong enough to carry the weight.

- Dialogue as a Weapon: Every word Hartman says is designed to elicit a physical reaction. Use dialogue to "attack" your characters.

- The Power of Improv: Even a genius like Kubrick knew when to step aside for a real expert (Ermey).

- Theme Over Plot: The "Duality of Man" isn't just a line; it's the structural foundation of the entire movie.

- Atmosphere Through Pacing: The slow, grueling pace of the first half makes the chaotic, fast-paced second half feel even more jarring.

If you want to really understand how this movie works, you have to look past the "memes" and the drill sergeant clips on YouTube. You have to look at how the full metal jacket movie script builds a world that is intentionally ugly. It doesn't want you to be comfortable. It doesn't want you to like the characters. It just wants you to see the process of how a human being is turned into a weapon and then discarded.

Next time you watch it, pay attention to the silence. Kubrick and Herr knew that sometimes, the most powerful part of a script is what the characters don't say while they’re staring into the void of a burning city.

Actionable Insights for Your Next Project

If you’re looking to analyze or write something with this level of impact, focus on these steps:

- Deconstruct your protagonist's contradictions. Give them a "peace sign" and a "born to kill" helmet—metaphorically speaking. What two opposing forces drive them?

- Study military jargon and "slang" from the era. Authentic dialogue isn't just about what is said, but the specific rhythm and terminology of the subculture you're writing about.

- Read Gustav Hasford’s "The Short-Timers." Seeing how Kubrick stripped the book down into the full metal jacket movie script is a masterclass in adaptation. You’ll see exactly what he kept (the grit) and what he threw away (the unnecessary subplots).

- Practice writing long-form insults or monologues. Try to maintain a character's voice for two full pages without a break. It’s harder than it looks and helps define a character's dominance in a scene.

The script remains a brutal, essential piece of cinema history because it refuses to apologize for what it is. It’s cold, it’s clinical, and it’s perfectly executed. By looking at the evolution from Hasford's prose to Herr's grit and Kubrick's vision, you get a clear picture of how a masterpiece is actually assembled—piece by painful piece.