Hydrogen sounds like a miracle on paper. You take some gas, run it through a membrane, and out comes electricity and water. No carbon. No smog. Just clean power. But if you talk to the engineers at companies like Bosch or Ballard Power Systems, they’ll tell you the same thing: it’s the plumbing that kills you. Specifically, the fuel cell fuel pump.

Think about it.

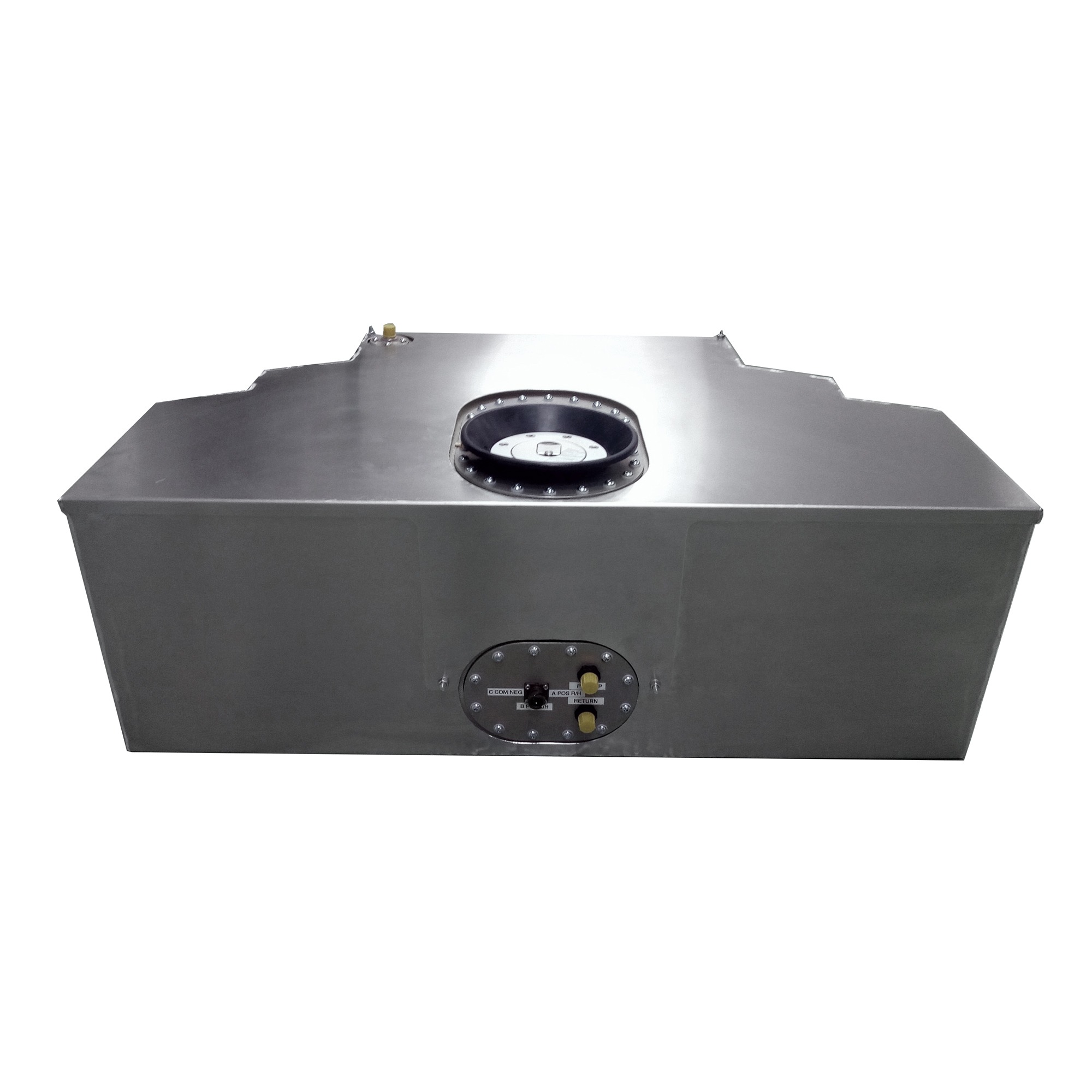

In a standard internal combustion engine, the fuel pump just has to shove liquid gasoline down a line. Easy. But in a hydrogen fuel cell vehicle (FCEV), that pump—often referred to as the hydrogen recirculation blower or the anode recirculation pump—is dealing with a temperamental, leaky, and incredibly light gas. It has to move hydrogen back through the system to keep the reaction going without letting any of it escape. If that pump fails, the whole stack dies. Honestly, it’s one of the most overlooked pieces of tech in the entire green energy transition.

The Brutal Reality of Moving Hydrogen gas

Hydrogen is a nightmare for moving parts. It’s the smallest molecule in the universe. It finds gaps that air or oil wouldn't even notice. Because of this, a fuel cell fuel pump can't just use standard seals. If you use a traditional rubber seal, the hydrogen molecules will literally migrate through the material. This leads to "hydrogen embrittlement," where the metal parts of the pump become brittle and crack like old glass.

Engineers have to get creative. They use specialized coatings and "dry" bearings. Why dry? Because if you use oil to lubricate the pump and even a tiny droplet gets into the fuel cell stack, it poisons the catalyst. You've basically just turned a $50,000 fuel cell into a very expensive paperweight.

Most people think the "fuel" in a fuel cell is just sitting there waiting to be used. It's not. It’s constantly being cycled. The pump has to handle a mix of hydrogen, water vapor, and nitrogen. It’s a wet, corrosive, and high-speed environment. Most recirculation pumps operate at incredibly high RPMs—sometimes over 15,000—just to keep the flow consistent. It’s loud. It’s violent. And it has to be perfectly silent for the passenger.

Why we can't just use a "normal" pump

Standard pumps rely on the density of the fluid to create pressure. Hydrogen has almost no density. Pushing it is like trying to sweep dust with a hula hoop. You need high-precision impellers. Companies like Busch Vacuum Solutions have spent years perfecting side-channel blowers that can handle these low-density gases without wearing out in six months.

📖 Related: How to actually make Genius Bar appointment sessions happen without the headache

The Efficiency Trap

Every watt of electricity used by the fuel cell fuel pump is a watt that isn't going to the wheels. This is the "parasitic load." In early prototypes, these pumps were so power-hungry that they significantly dropped the vehicle's range.

Today, the focus is on integration.

- Some designs use the pressure of the incoming hydrogen from the tank to drive a "jet pump" or ejector.

- This uses the Venturi effect to pull recirculated gas back into the stream without needing an electric motor at all.

- The problem? Ejectors only work well at high loads.

- At idle or low speeds, you still need an active electric pump to keep the stack from "choking" on water buildup.

It’s a balancing act. You’ve basically got to design a system that works at a crawl in stop-and-go traffic but doesn't melt down when the truck is hauling 40 tons up a mountain pass.

Real-World Stakes: From Mirai to Class 8 Trucks

Take the Toyota Mirai or the Hyundai Nexo. These aren't just science experiments; they are production cars. The fuel cell fuel pump in a Mirai has to be small enough to fit under the chassis but tough enough to last 150,000 miles.

Then you look at the heavy-duty sector.

Companies like Nikola and Daimler Truck are betting big on hydrogen for long-haul freight. For a semi-truck, the fuel cell stack is massive. The pump requirements scale up accordingly. We are talking about blowers that need to move massive volumes of gas while maintaining a hermetic seal. If a pump fails on a highway in the middle of Nebraska, that driver is stranded with a dead high-voltage system. The reliability standards are insane.

👉 See also: IG Story No Account: How to View Instagram Stories Privately Without Logging In

Water Management is the Secret Boss

Here is something most people miss: the pump isn't just moving hydrogen. It’s moving water. Fuel cells produce water as a byproduct. Some of that water ends up in the anode (the hydrogen side). If that water isn't cleared out by the pump’s flow, it creates "flooding."

Imagine trying to breathe through a straw that’s half-full of water. That’s what happens to a fuel cell when the recirculation pump isn't tuned correctly. The power drops, the voltage fluctuates, and eventually, the stack shuts down to prevent damage. So, the pump is actually a water management tool as much as a fuel delivery system.

The Cost Factor

Why is your neighbor not driving a hydrogen car? Cost is the big one. And the fuel cell fuel pump is a contributor. These aren't mass-produced like the fuel pumps in a Ford F-150. They require exotic materials like stainless steel alloys, ceramic bearings, and specialized electronics to handle the high-speed motors.

We are currently in the "scaling" phase. As more hydrogen trucks hit the road, the cost of these specialized pumps will drop. But right now, you're looking at a component that costs five to ten times more than its gasoline counterpart.

Future Tech: Are We Moving Away From Mechanical Pumps?

There is a lot of talk about "passive" recirculation.

The idea is to use a series of ejectors and valves to eliminate the moving parts entirely. If you have no motor, you have no bearings to fail and no seals to leak. It’s the "holy grail." However, the physics are stubborn. Hydrogen fuel cells are dynamic. They need different flow rates depending on whether you’re accelerating or coasting.

✨ Don't miss: How Big is 70 Inches? What Most People Get Wrong Before Buying

For now, the hybrid approach seems to be winning. You use a small electric fuel cell fuel pump for low-power states and an ejector for high-power states. It’s more complex, but it’s the only way to get the efficiency numbers where they need to be for commercial viability.

The Maintenance Headache

If you own a fuel cell vehicle, you don't do "oil changes." But you do have to worry about the coolant and the mechanical integrity of the balance-of-plant (BoP) components. The pump is the heart of that BoP. If you hear a high-pitched whine that sounds like a jet engine starting up under your car, your pump's bearings might be on their way out.

Actionable Insights for the Hydrogen Industry

If you're looking into hydrogen tech—whether as an investor, an engineer, or just a curious consumer—pay attention to the "Balance of Plant." The stack gets all the glory, but the peripherals like the fuel cell fuel pump determine the lifespan of the vehicle.

- Watch the Bearings: Look for companies moving toward air-foil bearings or magnetic bearings. These eliminate the need for lubricants entirely, which is the number one cause of stack degradation.

- Ejector Integration: The most efficient systems in 2026 are using "active ejectors." These combine the simplicity of a venturi with a small moving needle to adjust flow. It’s the best of both worlds.

- Material Science Matters: Don't ignore the housing. Aluminum is light, but it’s susceptible to corrosion in the wet hydrogen environment. Look for high-grade stainless or specialized composite housings.

- Thermal Management: A pump that runs hot is a pump that dies early. Integrated cooling loops that tie the pump into the main fuel cell stack's thermal management system are becoming the standard for heavy-duty applications.

The dream of a hydrogen economy doesn't live or die by the fuel cell stack alone. It lives or dies by the ability to move that gas reliably, quietly, and efficiently. The humble pump might just be the most important piece of the puzzle we have left to solve.

Next Steps for Implementation

For those designing or maintaining these systems, the priority is clear: transition to oil-free operation as soon as the budget allows. If you are evaluating a fuel cell system for a fleet, demand the MTBF (Mean Time Between Failure) data specifically for the recirculation blower. It is historically the "weak link" in the chain. Ensure your maintenance schedule includes vibration analysis on the pump housing; catching a bearing failure early can save the entire fuel cell stack from catastrophic contamination.

Check the seals. Verify the material compatibility. And remember that in the world of hydrogen, the smallest leak is a massive problem.