History isn't a straight line. People often look at a free slave states map and see a clean, jagged border—the Mason-Dixon Line—separating a "good" North from a "bad" South. But if you actually spend time digging through the archives of the Library of Congress or reading the census data from 1850, you realize the reality was a messy, tangled disaster of legal loopholes and human tragedy.

It wasn't just a map. It was a ticking time bomb.

The Lines We Draw

Most of us remember the basics from middle school. There was the Missouri Compromise of 1820. That was the big one. It basically told the country that anything north of the 36°30′ parallel would be free, and anything south would be slave territory. Simple, right? Except it wasn't. Missouri itself was a slave state that sat almost entirely north of that line. It was a geographic anomaly that drove abolitionists crazy.

When you look at a free slave states map from the mid-19th century, you’re looking at a visual representation of a cold war. Every time a new state like California or Texas tried to join the union, the whole country had a collective panic attack. Why? Because the map was about power in the Senate. If the "free" side got too many states, the "slave" side lost their ability to protect their "property." It was a numbers game played with human lives.

The "Free" North Wasn't Always Free

Here is the thing that honestly trips people up. We talk about New York or New Jersey as free states. But if you looked at a map in 1830 or 1840, you’d still find enslaved people in those places. New Jersey was notoriously slow. They passed a "gradual emancipation" law in 1804. Basically, it meant if you were born to an enslaved mother after a certain date, you were free—but only after you served your mother's "owner" for 25 or 28 years.

By 1860, the census still listed eighteen "apprentices for life" in New Jersey. They were effectively enslaved. So, when someone shows you a free slave states map and colors New Jersey solid blue, they’re kinda lying by omission. The transition from slave to free was a grueling, decades-long process that left thousands in a legal limbo that felt a lot like slavery.

The Fugitive Slave Act Ruined the Map

In 1850, everything changed. The Fugitive Slave Act was passed, and it basically turned the entire United States into a hunting ground. Even if you lived in a "free" state like Massachusetts or Ohio, you weren't actually in a free zone anymore. Federal marshals could deputize any citizen to help catch a runaway.

✨ Don't miss: Election Where to Watch: How to Find Real-Time Results Without the Chaos

If you refused? You went to jail.

This act made the free slave states map functionally obsolete for Black Americans. The border didn't protect you. A person could be kidnapped in the middle of Boston and dragged back to a plantation in Georgia because a white person claimed they "owned" them. The legal protections of the North evaporated overnight. This is why you saw the Underground Railroad push all the way to Canada. "Free" states weren't safe enough anymore.

The Chaos of Bleeding Kansas

If you want to understand how a map leads to a war, look at Kansas. In 1854, the Kansas-Nebraska Act tossed the Missouri Compromise out the window. It said the people living there could vote on whether to be a free or slave state.

Total chaos.

Pro-slavery "Border Ruffians" from Missouri crossed over to rig elections. Abolitionists like John Brown showed up with broadswords. People were literally killing each other over where a line on the map would fall. This wasn't some abstract political debate. It was a bloody preview of the Civil War. When we look at a historical free slave states map, Kansas is often shaded in a way that hides the fact that it was a war zone for years before the first shots were fired at Fort Sumter.

Why We Still Misunderstand the West

The West is often ignored. We think of the Civil War as an East Coast thing. But the free slave states map stretched all the way to the Pacific. California entered as a free state in 1850, but it had its own weird, dark history with the "Act for the Government and Protection of Indians." It allowed for the indentured servitude of Native Americans.

🔗 Read more: Daniel Blank New Castle PA: The Tragic Story and the Name Confusion

So, was it a "free" state? On the official map, yes. In practice? It was complicated.

Then you have Utah and New Mexico territories. Under the 1850 Compromise, they were "popular sovereignty" areas. They could choose. And they did have enslaved populations, though they were small compared to the Cotton Kingdom of the Deep South. The map was shifting constantly, like sand.

The Economic Engine Behind the Colors

We can't talk about these maps without talking about money. The Southern states weren't just "choosing" slavery; their entire economy was a machine built on forced labor. By 1860, the total value of enslaved people in the United States was roughly $3 billion. That was more than the value of all the railroads and factories in the North combined.

When you see a free slave states map, you’re seeing a map of two different economic systems. One was industrializing and moving toward wage labor (though often under brutal conditions in Northern factories), and the other was a feudalistic agrarian society. The map shows a collision course between two versions of America that couldn't coexist.

Real Evidence: The 1860 Census

If you want the most accurate version of this map, you have to go to the 1860 Census data. It’s haunting.

- South Carolina: 57% of the population was enslaved.

- Mississippi: 55% of the population was enslaved.

- Delaware: A "slave state" that stayed in the Union, but had fewer than 1,800 enslaved people left.

These nuances matter. A "slave state" like Delaware or Maryland looked very different from a "slave state" like Alabama. The Northern tier of slave states—the Border States—eventually became the hinge upon which the Civil War turned. Lincoln famously said he hoped to have God on his side, but he must have Kentucky.

💡 You might also like: Clayton County News: What Most People Get Wrong About the Gateway to the World

Surprising Details People Miss

Many people think slavery ended everywhere the moment the Emancipation Proclamation was signed in 1863. Nope. That only applied to states in rebellion. If you lived in a slave state that stayed loyal to the Union—like Kentucky or Delaware—the Emancipation Proclamation didn't free you.

You had to wait for the 13th Amendment in 1865.

This means that for a couple of years, the free slave states map was the weirdest it had ever been. There were enslaved people in Union-controlled areas who were legally still "property," while people in the Confederate South were "legally" free but still under the thumb of their oppressors.

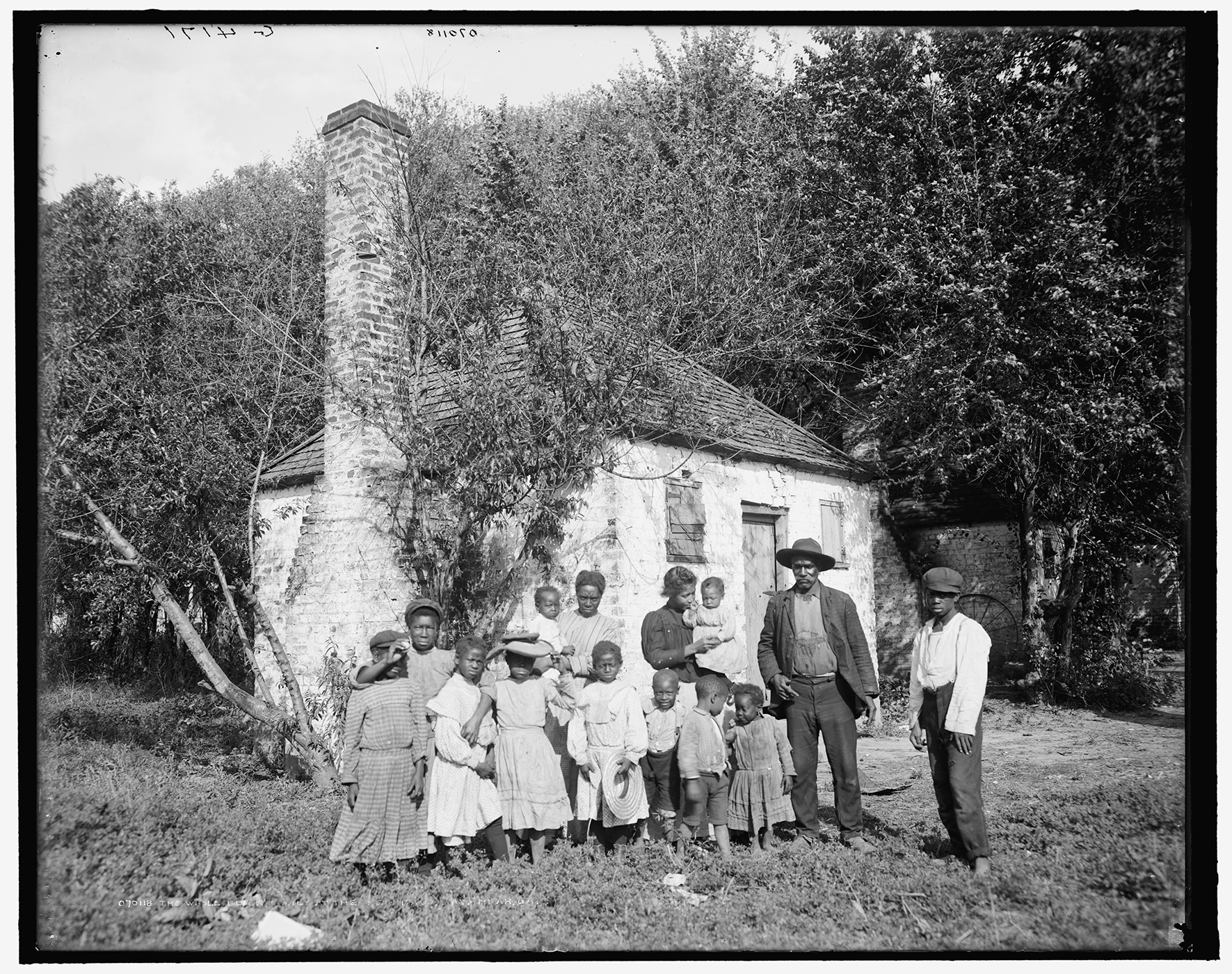

Moving Beyond the Paper Map

To truly understand the free slave states map, you have to stop looking at it as a static image in a textbook. It was a living, breathing document of conflict. It represented where a Black man could walk without a pass, where a family could stay together without being sold, and where the law of the land was written in blood.

The borders we see today—the straight lines of the Midwest and the jagged edges of the East—are the scars of those old arguments. We still live in the geography those maps created.

Actionable Insights for Researching Historical Maps

- Check the Date: A map from 1820 looks nothing like a map from 1854. Always verify the year to understand which "Compromise" was in effect.

- Look for the "Border States": Specifically study Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland, and Delaware. These were slave states that did not secede, and they are the key to understanding why the war was so complicated.

- Investigate Local Laws: "Free" didn't always mean "Equal." Many free states had "Black Laws" that prevented Black people from voting, serving on juries, or even moving into the state.

- Use Primary Sources: Go to the Library of Congress digital collections. They have high-resolution scans of original maps from the 1850s that show the specific "Slave Density" by county.

- Verify Territorial Status: Remember that "Territories" weren't states. Places like Nebraska or New Mexico were often in a state of legal flux where slavery was "legal" but not widely practiced.