It is dark. You are sitting in your car, which is tucked inside a massive, brightly lit shuttle, hurtling through the bedrock beneath the English Channel at 140 kilometers per hour. Most people just call it the Chunnel. To the engineers who spent years sweating over TBMs (Tunnel Boring Machines) and seismic sensors, it is officially the Channel Tunnel. But honestly, the France United Kingdom tunnel is a bit of a psychological trip if you stop to think about the sheer weight of the ocean pressing down on the chalk marl above your head. It’s one of those things we take for granted now, like high-speed internet or smartphones, but for centuries, the idea of linking Britain to mainland Europe was considered a pipe dream—or a military nightmare.

Napoleon liked the idea. He actually had a plan back in 1802 involve oil lamps and horse-drawn carriages. Imagine the logistics of that mess. Ventilation? Manure management? It would have been a disaster. Then the Victorians tried, and you can still see the abandoned shafts near Folkestone if you know where to look. They stopped because the British were terrified that a tunnel would basically be an invitation for a French invasion. Fear is a powerful motivator for staying isolated.

The day the breakthrough actually happened

The real magic happened on December 1, 1990. Graham Fagg and Phillippe Cozette became the faces of a new era. They were the workers who broke through the service tunnel, shaking hands through a small hole while the world watched on grainy TV feeds. It wasn’t a clean, cinematic explosion. It was a dusty, loud, and incredibly precise meeting of two massive machines that had started on opposite sides of the sea.

They met almost perfectly. The deviation was tiny—about the size of a coffee table. When you consider they started 50 kilometers apart, that’s insane. The France United Kingdom tunnel isn't just one tube; it’s actually three. You have two rail tunnels and a smaller service tunnel in the middle for maintenance and emergencies. That middle one is the reason you don't feel claustrophobic—it’s the safety valve of the whole operation.

Why does it cost so much?

Let’s talk money because the finances were, frankly, a train wreck for a long time. The project was entirely privately funded. Not a single cent—or penny—of taxpayer money went into the initial construction. This sounds great on paper until you realize the budget blew up. It cost about £9 billion in 1990s money. If you adjust that for today’s inflation, we’re talking about a sum that would make most small nations sweat.

Eurotunnel, the company that runs the show (now under the Getlink brand), struggled with debt for decades. They’ve had to restructure more times than most people change their oil. But the volume is there. We're talking millions of trucks, cars, and Eurostar passengers every single year. It’s the literal backbone of trade between the UK and the EU. Even with the political headaches of the last few years, the physical link remains unbreakable.

The weird science of the seabed

The geology of the Channel is the only reason this worked. Engineers looked for the "Chalk Marl." It’s this specific layer of rock that is mostly waterproof and relatively easy to grind through. If the seabed had been solid granite or loose sand, the France United Kingdom tunnel would have been impossible or significantly more expensive.

The TBMs were the real heroes. These weren't just drills; they were mobile factories. They moved forward, chewed the rock, spat it out onto a conveyor belt, and lined the walls with concrete segments all at the same time. The British machines were slightly different from the French ones because the ground conditions weren't identical. The French side had more fractured rock and water pressure issues, so their machines had to be sealed like submarines.

- The tunnels sit an average of 45 meters below the seabed.

- Total length is about 50.45 kilometers.

- The journey takes about 35 minutes.

- It is still the longest undersea portion of any tunnel in the world.

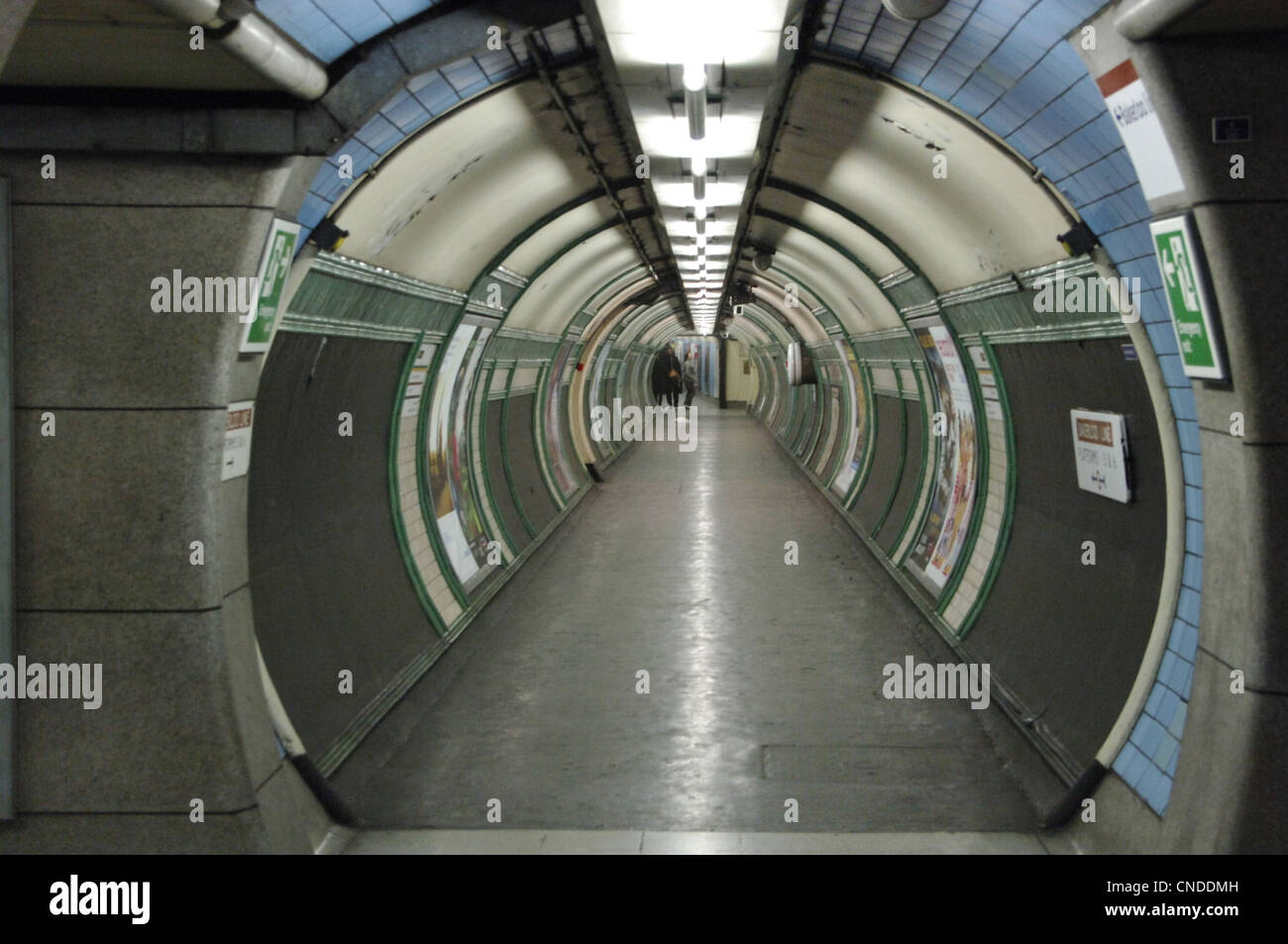

Logistics and the "Le Shuttle" experience

If you’ve never done it, driving onto the shuttle is a weird experience. You don't stay in your car for a "drive," you stay in it while the train moves. It feels like being in a very long, very clean garage that happens to be moving through the earth.

There’s a common misconception that you can drive your own car through the tunnel like a regular road. You can’t. There is no road. It would be a carbon monoxide nightmare. You have two choices: take the Eurostar (the passenger train) or put your car on the Eurotunnel Le Shuttle.

The Brexit factor and the border

Things got complicated recently. For a long time, the France United Kingdom tunnel was the poster child for a borderless Europe. You could zip from London to Paris in just over two hours with barely a glance at your passport. Now, the checks are a bit more rigorous.

The "Juxtaposed Controls" are what make it work. Basically, French customs are in the UK, and British customs are in France. You clear everything before you even get on the train. It's efficient, but the post-2020 world added layers of bureaucracy that the original designers probably didn't envision when they were dreaming of a seamless link. Despite the paperwork, the sheer speed still beats the ferry for most travelers. A ferry takes 90 minutes; the tunnel takes 35. You do the math.

Security and the things nobody talks about

Safety is the obsession of the tunnel operators. Fire is the biggest enemy. There have been a few fires over the years—notably in 1996 and 2008—usually involving HGVs (Heavy Goods Vehicles). The cooling systems are massive. There are two huge refrigeration plants on either side that circulate cold water to keep the air temperature from soaring because the friction of the trains generates a massive amount of heat.

Then there’s the pressure. When a train enters the tunnel at high speed, it pushes a column of air in front of it. Without relief ducts, that pressure would build up and potentially damage the trains or the tunnel lining. Engineers built "piston relief ducts" that connect the two main rail tunnels, allowing the air to move around and balance out. It's basically the tunnel's way of breathing.

Environmental impact and the future

Building this thing wasn't exactly "green" in the 1980s sense, but the long-term impact is interesting. Taking a train through the France United Kingdom tunnel has a significantly lower carbon footprint than flying from Heathrow to Charles de Gaulle. It’s not even close.

What’s next? There are always rumors of a second tunnel. The current capacity is high, but as we move toward more sustainable travel, the demand for rail over air is only going up. Could we see a dedicated freight-only tunnel? Or maybe a hyperloop-style upgrade? Probably not anytime soon given the price tag, but the infrastructure is designed to last at least 120 years. We are only 30 years in.

Reality check: Common myths

People think the tunnel is a glass tube where you can see fish. Honestly, that would be terrifying and structurally impossible at those depths. It’s concrete. Lots and lots of concrete. Another myth is that it’s prone to leaking. While there is some seepage—every tunnel has it—the pumping systems are over-engineered to handle way more water than ever actually gets in.

You also might hear that it's "too expensive" compared to the ferry. It depends on when you book. If you're a "turn up and go" traveler, yes, it will sting your wallet. But if you plan ahead, the convenience of staying in your car with your dog and your luggage usually outweighs the cost.

How to make the most of your crossing

If you are planning a trip through the France United Kingdom tunnel, don't just show up and hope for the best.

- Book the "Frequent Traveller" flexi-plus if you can. It lets you skip the queues, and if you're doing the crossing more than a few times a year, it pays for itself in time saved.

- Check the pet rules. This is the number one way people cross with dogs. It’s way less stressful than a ferry or a plane, but the paperwork (animal health certificates) has to be perfect.

- Charge your EV. There are massive charging hubs at both the Folkestone and Calais terminals. Use them while you wait for your boarding letter.

- Don't forget the duty-free. Since the UK left the EU, duty-free is back. The shops at the terminals are actually worth a look now if you're into that sort of thing.

The tunnel is a reminder of what happens when two nations stop arguing long enough to build something that literally moves mountains—or at least goes under them. It is a bit of 20th-century grit that still feels like 21st-century tech. Next time you're down there, just remember Graham and Phillippe shaking hands in the dark, and maybe the 35-minute wait won't seem so long.

Actionable Insights for Travelers

- Timing: Mid-week crossings (Tuesday/Wednesday) are almost always 30% cheaper than weekend slots.

- Arrival: The terminal works on a letter system (A, B, C...). Aim to arrive 45-60 minutes before your slot; if you're early and there's space, they often put you on an earlier train for free.

- Documentation: Keep your booking reference and passports in an easy-to-reach spot. You will scan them at a booth without even getting out of your car.

- Supplies: Stock up on snacks at the terminal buildings. Once you are in the "boarding lanes," there are no shops or toilets until you get onto the train itself.