Henry Ford was kind of obsessed. Not just with cars, but with the idea that he shouldn't have to depend on anyone else to make them. He wanted a place where iron ore went in one end and a finished Model A rolled out the other. That place became the Ford River Rouge Complex. It wasn't just a factory; it was a self-contained city that basically rewrote the rules of global manufacturing. Honestly, if you look at how Tesla builds cars today or how Amazon manages its logistics, you're seeing the DNA of "The Rouge" everywhere. It is the original blueprint for vertical integration.

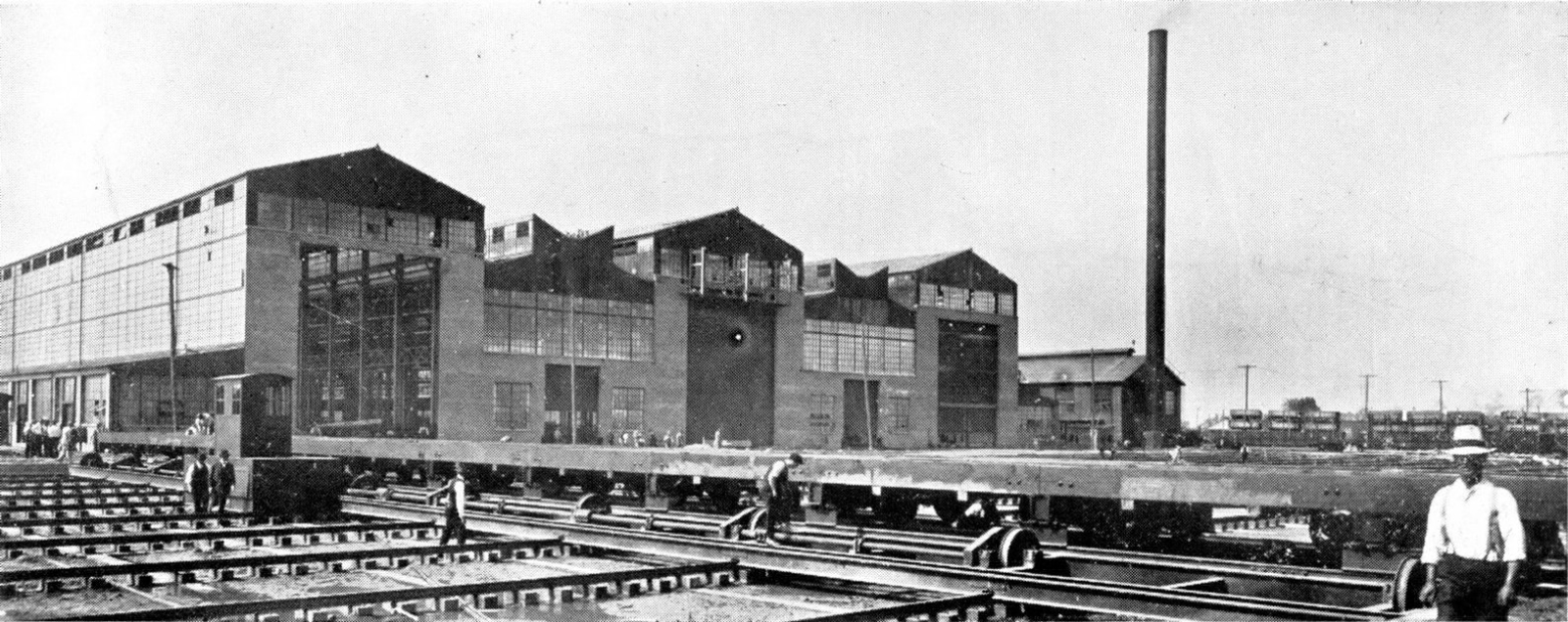

The scale of the place is hard to wrap your head around even now. In the 1920s, it was the largest integrated factory in the world. We’re talking over 90 buildings, 100 miles of internal railroad track, and its own power plant. At its peak, it employed over 100,000 people. Imagine a hundred thousand people showing up to the same patch of land in Dearborn every single day. It’s wild.

The Raw Power of Vertical Integration at the Rouge

Most people think of assembly lines when they think of Ford, but the Ford River Rouge Complex was about something much bigger: control. Ford hated being at the mercy of suppliers. So, he built a port on the Rouge River so his own ships could bring in iron ore from his own mines in Minnesota and coal from his own mines in Kentucky. He even had his own timberlands and a glass plant.

He did it. He actually achieved the "ore-to-assembly" dream.

👉 See also: Mark Singer Gorilla Glue Net Worth: Why the Inventor Walked Away

Within about 28 hours, raw iron ore arriving at the docks would be transformed into steel, cast into an engine block, and installed into a finished vehicle. That kind of speed is still impressive by 2026 standards. It eliminated the middleman, cut down on shipping costs, and allowed Ford to keep the price of the car low enough for the people building it to actually buy one.

But it wasn't all just industrial magic. The sheer density of the site created a high-pressure environment. Because everything was so tightly linked, a problem in the steel mill could grind the entire vehicle assembly to a halt within hours. There was no "safety stock." It was the precursor to "Just-in-Time" manufacturing, but on a terrifyingly massive scale.

Labor, Tension, and the Battle of the Overpass

You can't talk about the history of the Ford River Rouge Complex without talking about the violence that happened there. It wasn't always a happy success story for the workers. Henry Ford famously employed the "Ford Service Department," which was basically a private police force led by Harry Bennett. They were there to keep the union out, and they weren't subtle about it.

May 26, 1937. That's the date of the Battle of the Overpass.

United Auto Workers (UAW) organizers, including Walter Reuther, were trying to hand out leaflets on a pedestrian overpass leading to Gate 4. Bennett’s "service men" didn't just ask them to leave. They beat them bloody. It was a PR nightmare for Ford because photographers were there to capture the whole thing. The images of bruised and battered organizers circulated globally, shifting public opinion in favor of the labor movement. It took a few more years and a massive strike in 1941, but eventually, the Rouge became a union shop.

This tension defines the site’s legacy. It represents the peak of American industrial might, but also the peak of the struggle for workers' rights. You see both sides of the coin in Dearborn.

Survival in the Post-Industrial Age

By the 1970s and 80s, the Ford River Rouge Complex started to look like a relic. The world was moving toward smaller, specialized plants. The massive, smoke-belching chimneys of the Rouge felt out of step with an era of environmental regulations and global competition. A lot of people thought Ford would just level the place and move on.

They didn't.

Instead, Bill Ford Jr. spearheaded a massive revitalization in the early 2000s. He wanted to prove that "old industry" could be "green industry." They installed a massive living roof—over ten acres of sedum—on the new Dearborn Truck Plant. It sounds like a gimmick, but it actually manages stormwater and helps insulate the building, saving millions in infrastructure costs.

Today, the Rouge is the home of the F-150 Lightning. It’s sort of poetic. The site that was built to turn coal and iron into internal combustion engines is now the hub for Ford’s electric future. The Rouge Electric Vehicle Center is a "factory within a factory," using autonomous guided plateforms instead of traditional fixed conveyor belts. It’s a lot quieter than the old days.

Why the Rouge is Different from Modern Gigafactories

You’ll hear people compare the Rouge to Tesla’s Gigafactories or Intel’s chip plants. There’s a grain of truth there, but the Rouge is a different beast. Modern plants are often "clean." They assemble parts made elsewhere. The Rouge, even in its modern form, still retains that "heavy" feel. You still have the steel making, the stamping, and the assembly all happening in one massive ecosystem.

- It’s 600 acres of active industrial land.

- It still uses the river for logistics.

- The history is physically layered into the soil.

When you walk through the tour—which, honestly, if you're ever in Michigan, you should do—you realize how thin the line is between 1924 and 2026. The tech changes, but the physics of moving heavy stuff around a room remains the same.

The Environmental Elephant in the Room

We have to be real: an industrial site this big leaves a footprint. For decades, the Rouge River was one of the most polluted waterways in the country. It famously caught fire. More than once.

The cleanup efforts over the last thirty years have been massive, but it's an ongoing process. Ford has invested heavily in phytoremediation—using plants to draw toxins out of the soil. It’s a slow-motion battle against a century of heavy metals and oils. While the "Green Roof" is the flashy part of the story, the real work is happening in the dirt and the water. It serves as a case study for how we handle "brownfield" sites. You can't just walk away from a century of manufacturing; you have to actively heal the land while you're still using it.

Practical Insights for History Buffs and Business Owners

If you're looking at the Ford River Rouge Complex as a model for business or just a point of interest, here are the actual takeaways.

First, vertical integration is a double-edged sword. It gives you total control over your supply chain, which is great during a global shortage, but it makes your overhead massive. Most companies today prefer to be "asset-light." Ford went "asset-heavy," and it nearly broke them several times, but it also gave them a foundation no one else has.

Second, a brand's history is an asset. Ford doesn't hide the Rouge's gritty past. They lean into it. They’ve turned a working factory into one of Michigan's biggest tourist attractions. There is immense value in showing people how things are actually made. In a world of digital products and "apps," seeing a 6,000-ton press stomp a piece of steel into a truck door is a visceral reminder of reality.

Finally, adaptability is the only way to survive a century. The Rouge has transitioned from the Model A to the V8 era, through World War II bomber production, the decline of the 70s, and now the shift to EVs.

Next Steps for Your Research:

- Visit the Henry Ford Museum: If you want to see the scale, book the Rouge Factory Tour in Dearborn. It’s one of the few places you can see a modern assembly line from an elevated walkway.

- Read "The People's Tycoon" by Steven Watts: It gives the best context on Henry Ford’s mindset when he was designing the Rouge.

- Check the EPA's Rouge River Project updates: If you're interested in the environmental side, the data on the river's recovery is publicly available and shows the reality of industrial cleanup.

- Study the 1941 Strike: Look into the archives of the Detroit Historical Society to understand how the labor shifts at the Rouge changed American middle-class life.