Six weeks. That is all it took to dismantle the idea that Florida was a safe bet for homeowners. Before the summer of 2004, the state had seen its share of brushes with disaster, but nothing prepared the peninsula for a relentless, month-and-a-half-long bombardment that felt like a vengeful atmospheric glitch. If you lived there then, you remember the blue tarps. You remember the sound of generators humming in the humidity. You definitely remember the names Charley, Frances, Ivan, and Jeanne.

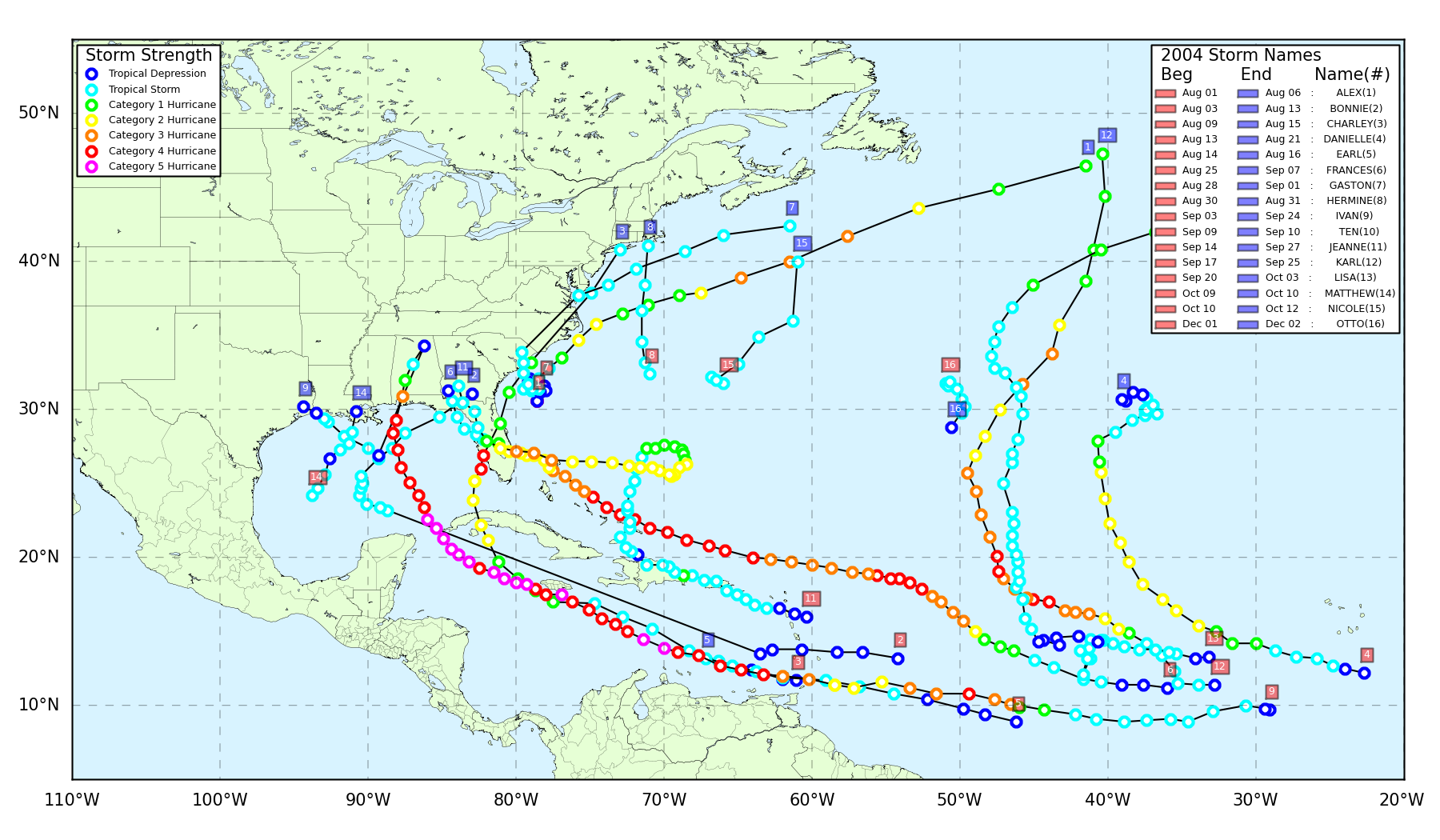

The Florida hurricanes in 2004 weren't just a series of bad storms; they were a systemic shock that rewrote the rules of emergency management and property insurance. For the first time since record-keeping began in 1851, four hurricanes hit a single state in one season. It was a statistical anomaly that felt personal to the millions of residents who spent August and September crisscrossing the state in search of ice, plywood, and a functioning cell tower. Honestly, the sheer exhaustion of that year is something people outside the South struggle to grasp. You’d clean up the debris from one storm just to see the spaghetti models for the next one aiming straight for your driveway.

The Chaos of Charley and the Charley-Effect

It started with Charley. On August 13, 2004, this compact, terrifyingly intense Category 4 hurricane decided to take a sudden right turn. People in Tampa were hunkered down, expecting a direct hit, while folks in Punta Gorda and Port Charlotte were relatively unprepared. When Charley slammed into Cayo Costa, it brought 150 mph winds that basically turned mobile home parks into scrap metal. It moved fast. It was like a giant tornado cutting a path across the state toward Daytona Beach.

This storm was a wake-up call for the National Hurricane Center (NHC) and the public alike. The "skinny" of the forecast cone—that little line in the middle—is what people focused on, ignoring the fact that the entire cone represents the margin of error. Max Mayfield, the NHC director at the time, was practically shouting into every microphone he could find that the track could shift. It did. The result was $15 billion in damage from just that one "small" storm.

Frances and the Long Wait

If Charley was a sprint, Frances was a marathon. Two weeks later, on Labor Day weekend, Hurricane Frances crawled toward the East Coast. It was massive—nearly the size of the entire state. While it made landfall as a Category 2 near Sewall's Point, its slow forward speed was the real killer. It just sat there. It dumped rain until the ground was a sponge, and the winds stayed high enough for long enough to weaken structures that had survived decades of Florida weather.

You’ve got to realize how weird the vibe was back then. Gas stations were out of fuel. Grocery stores had empty shelves where the bread and water used to be. Disney World closed for only the third time in its history. People were starting to get "hurricane fatigue," a term that became very real as the 2004 season refused to let up.

📖 Related: NIES: What Most People Get Wrong About the National Institute for Environmental Studies

Ivan: The Panhandle’s Turn

While the peninsula was trying to figure out where to put all the downed oak trees, Hurricane Ivan was brewing in the Caribbean. This one was a monster. It reached Category 5 strength three different times before finally hitting the Florida-Alabama border as a Category 3 on September 16.

Ivan didn't just bring wind; it brought a storm surge that ate parts of Interstate 10. The Escambia Bay Bridge literally fell apart. Pieces of the highway were just... gone. It also did something incredibly bizarre: after crossing the Southeastern US and heading back out into the Atlantic, the remnants of Ivan looped back south, crossed Florida again as a tropical depression, and eventually hit Louisiana. It was like the storm was stalking the Gulf Coast.

Jeanne: The Final Blow

The cruelest part of the Florida hurricanes in 2004 was Jeanne. On September 26, Jeanne made landfall in almost the exact same spot as Frances had three weeks earlier. If you had a hole in your roof from Frances, Jeanne made sure the rest of your house was ruined. It hit as a Category 3, and for many, it was the breaking point.

Psychologically, Jeanne was devastating. Most people had run out of money for supplies, their insurance adjusters hadn't even visited yet from the first two storms, and the power grid was a mess. Florida Power & Light (FPL) had thousands of workers in the field, but you can’t fix a grid that keeps getting knocked down every 14 days.

The Economic Aftermath and the Insurance Crisis

We are still paying for 2004. Literally. The four storms combined caused over $45 billion in damage. This was the year that changed the Florida insurance market forever. Before 2004, many national carriers were still willing to write policies in the state. After 2004 (and the subsequent 2005 season with Wilma), the big players started pulling back or creating "Florida-only" subsidiaries to shield their national assets.

👉 See also: Middle East Ceasefire: What Everyone Is Actually Getting Wrong

- Citizens Property Insurance Corporation: This was supposed to be the "insurer of last resort." After 2004, it became one of the largest insurers in the state because private companies fled.

- The Hurricane Catastrophe Fund: The state had to scramble to ensure there was enough reinsurance to keep the whole system from collapsing.

- Building Codes: Florida had already improved codes after Andrew in '92, but 2004 proved that secondary damage—water intrusion through soffits and roof vents—was a massive problem that needed new engineering solutions.

State Farm, Allstate, and others realized that the "1-in-100 year" storm event model was flawed. You could have four "1-in-100 year" events in 44 days. That realization sent premiums skyrocketing, a trend that has only accelerated in the decades since.

Real Stories: Beyond the Statistics

Talk to a local who lived through it. They’ll tell you about the "blue tarp summer." For nearly a year, if you flew over Florida, the landscape was dotted with bright blue FEMA tarps covering damaged roofs. Roofers were booked out for 18 months. Scammers flooded the state, taking deposits from desperate homeowners and disappearing.

There was also a weird sense of community. Neighbors who hadn't spoken in years were sharing chainsaws and huddling around charcoal grills to cook the meat that was thawing in their dead freezers. It was a survivalist lifestyle forced upon a suburban population.

What Most People Get Wrong About 2004

A common misconception is that the winds were the only problem. Honestly, the cumulative saturation of the soil was the silent destroyer. By the time Jeanne hit, the ground couldn't hold any more water. Perfectly healthy trees were toppling over in 40 mph gusts because the earth was basically liquid. This "compounding effect" is now a major focus for FEMA and emergency planners. They no longer look at storms in isolation; they look at the "antecedent moisture" and the state of the infrastructure from previous hits.

Actionable Insights for Modern Florida Residents

If 2004 taught us anything, it’s that history is a persistent teacher. If you live in a hurricane-prone area, the "wait and see" approach died twenty years ago.

✨ Don't miss: Michael Collins of Ireland: What Most People Get Wrong

1. Audit your insurance policy now. Most people don't realize their hurricane deductible is a percentage (usually 2% to 10%) of the home's value, not a flat $500. If your home is worth $500,000, a 5% deductible means you’re on the hook for the first $25,000.

2. Secondary Water Resistance (SWR). When you re-roof, ensure your contractor uses a self-adhering polymer modified bitumen roofing underlayment (peel-and-stick). In 2004, thousands of homes stayed dry even after losing shingles because they had this layer.

3. Generator Safety is Non-Negotiable. More people died from carbon monoxide poisoning and generator fires in 2004 than from the actual wind in some counties. Never, under any circumstances, run a generator in a garage or near a window.

4. Document Everything. Take a video of every room in your house today. Open the drawers. Show the electronics. If another 2004 happens, having a digital record in the cloud will be the difference between a smooth claim and a multi-year legal battle.

The 2004 season wasn't just a weather event. It was a cultural pivot point for Florida. It ended the "frontier" mentality of coastal development and ushered in an era of high-cost hardening and rigorous engineering. We survived the year of four hurricanes, but the landscape—both physical and financial—is permanently altered. Look at your roof. Check your shutters. The next 2004 is a matter of "when," not "if."