You know that feeling when you watch a movie and it just smells like old library books and expensive rain? That's the vibe. Honestly, the film Howards End 1992 shouldn't work as well as it does. It’s a movie about property laws, class anxiety, and a stray umbrella. On paper, it sounds like a snooze-fest your history teacher would put on during a rainy Friday. But then you watch it, and you realize James Ivory and Ismail Merchant weren't just making a "costume drama." They were making a psychological thriller where the weapons are cutting remarks and social snobbery.

It’s been over thirty years. Think about that. In 1992, we were all listening to Nirvana and wearing flannel, yet this hyper-refined Edwardian tragedy became a massive cultural touchstone. It won three Oscars. It made Emma Thompson a superstar. Most importantly, it captured a specific kind of English tension that nobody has quite managed to replicate since, not even with the big budgets of modern streaming services.

The weirdly modern heart of a 100-year-old story

The movie is based on E.M. Forster’s 1910 novel. The plot is basically a three-way collision between different social classes in England. You’ve got the Schlegels (Margaret and Helen), who are these intellectual, artsy sisters with German roots. Then there are the Wilcoxes, who are "New Money" business types—stiff, pragmatic, and kinda heartless. Finally, you have Leonard Bast, a poor clerk who’s just trying to better himself but gets absolutely crushed by the gears of the system.

What people usually miss is that the film Howards End 1992 is actually about the death of idealism.

Margaret Schlegel, played by Emma Thompson in a performance that feels so lived-in you’d swear she actually lived in 1910, tries to "only connect." That’s the big theme. Connect the heart and the brain. Connect the rich and the poor. But the movie shows us that some gaps are just too wide to bridge. When Margaret marries Henry Wilcox (Anthony Hopkins), she thinks she can soften him. She thinks love and conversation can fix a man who views life like a balance sheet. She’s wrong. It’s brutal to watch.

Why Ruth Wilcox is the MVP

Vanessa Redgrave plays Ruth Wilcox, the first wife of Henry and the original owner of the house, Howards End. She’s only in the first act, but her presence haunts the entire two-hour-and-twenty-minute runtime. She represents a dying England—one tied to the soil and tradition rather than stocks and bonds.

When she leaves the house to Margaret on a handwritten scrap of paper on her deathbed, the Wilcox family just... burns it. They literally stand around a fireplace and toss her final wish into the flames because it doesn’t make sense to their business-oriented brains. It’s a small, quiet moment of pure villainy that sets the whole tragedy in motion.

💡 You might also like: Songs by Tyler Childers: What Most People Get Wrong

Looking at the technical mastery of Merchant Ivory

Ismail Merchant and James Ivory were a powerhouse. People use the term "Merchant Ivory" now as a shorthand for "boring people in corsets," but that’s such a lazy take. In the film Howards End 1992, the cinematography by Tony Pierce-Roberts is almost aggressive in its beauty. He uses natural light in a way that makes the dust motes in the air look like they were choreographed.

The pacing is also fascinatingly erratic. It’s slow until it’s suddenly, violently fast. One minute you’re watching a polite tea party, and the next, a character is being crushed by a falling bookcase in a scene that feels like something out of a horror movie.

The Hopkins and Thompson chemistry

We have to talk about Anthony Hopkins. This was right after The Silence of the Lambs. People expected him to be terrifying, and he is, but in a totally different way. As Henry Wilcox, he isn't eating people; he’s just ignoring their humanity. His Henry is a man who is terrified of emotion. There’s a scene where Margaret tries to get him to confront his past, and you can see his face literally shut down. It’s like watching a vault door close.

Thompson, on the other hand, is all nerves and empathy. She talks fast. she moves fast. She’s a whirlwind of intellectual energy. The contrast between her warmth and his coldness is the engine that drives the second half of the film.

The Leonard Bast problem

If there’s one part of the film Howards End 1992 that gets debated more than anything else, it’s the character of Leonard Bast (Samuel West). He’s the "poor" character. The Schlegels try to "help" him, but their help is actually a catastrophe. They give him bad job advice because they don't understand how the real world works, and he ends up unemployed and starving.

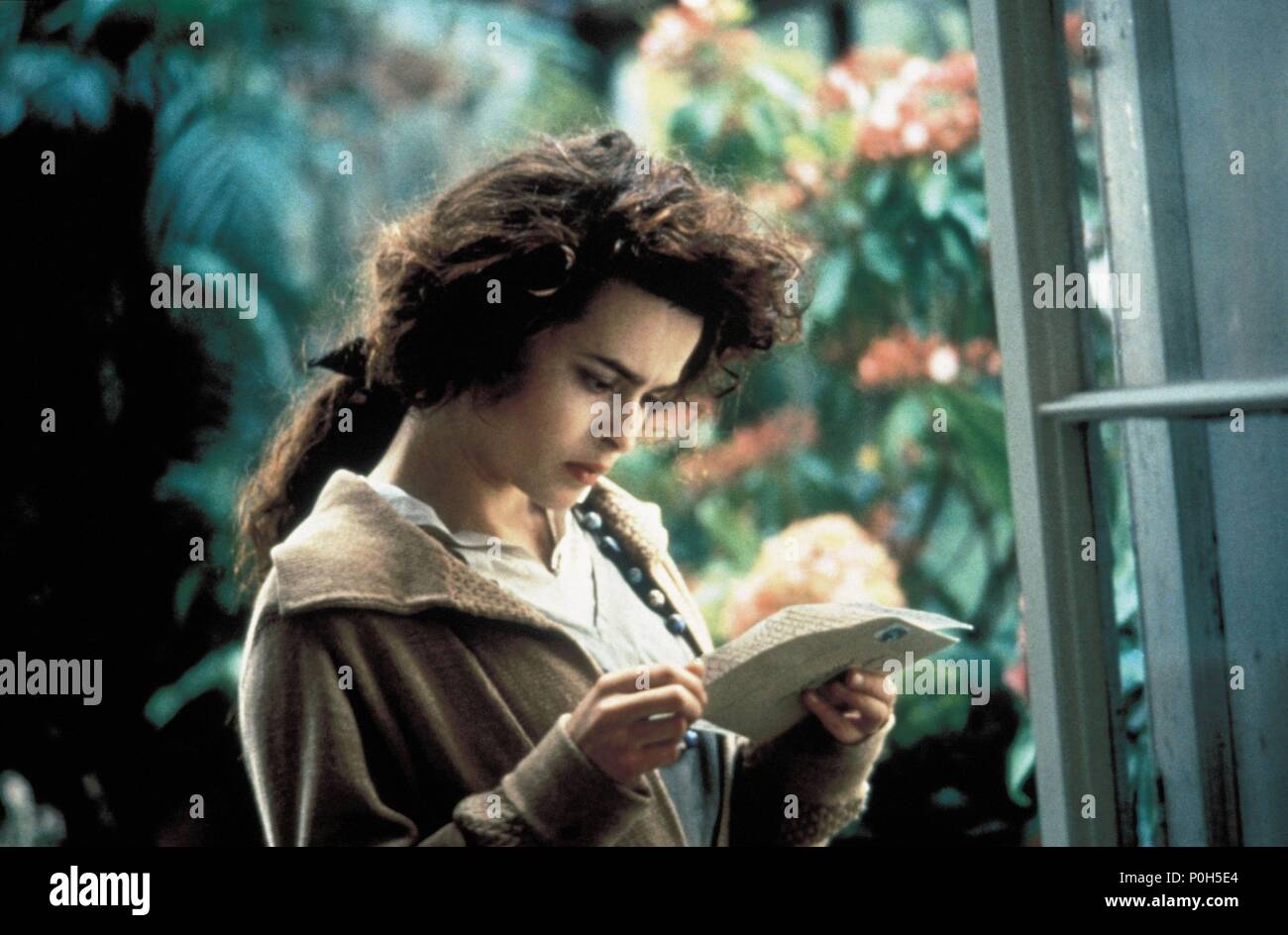

Some critics argue that Forster—and the film—treat Leonard as a symbol rather than a person. He’s the sacrificial lamb of the story. But honestly, watching it today, it feels like a scathing critique of "limousine liberals." The Schlegels mean well, but their privilege keeps them from seeing the actual danger Leonard is in. Helena Bonham Carter’s Helen Schlegel is especially guilty of this. She becomes obsessed with Leonard’s plight, but it’s more about her own rebellion against the Wilcoxes than it is about Leonard himself.

📖 Related: Questions From Black Card Revoked: The Culture Test That Might Just Get You Roasted

It’s messy. It’s uncomfortable. It’s exactly why the movie still feels relevant in an era of massive wealth inequality.

The house as a character

Howards End isn't just a building. It represents the soul of England. The movie spends a lot of time showing us the red bricks, the wych-elm tree, and the meadows. Production designer Luciana Arrighi won an Oscar for this, and you can see why. The house feels ancient and stable, a stark contrast to the smog-filled, chaotic London where the characters spend most of their time.

The struggle for who gets to live in that house is a struggle for who gets to define the future of the country. Will it be the intellectuals? The capitalists? The working class? The ending gives a messy, complicated answer that satisfies no one and everyone at the same time.

Fun facts you probably didn't know:

- The actual house used for Howards End was Peper Harow in Surrey, but the exterior shots were filmed at a house in Oxfordshire that actually belonged to a friend of E.M. Forster.

- Emma Thompson actually wrote letters to James Ivory to convince him she was right for the role, even though he initially thought she was too young.

- The budget was only about $8 million. In Hollywood terms, that's basically the catering budget for a Marvel movie today. They made a masterpiece for pennies.

- Jodhi May, who played the younger Schlegel sister in a stage version, was considered for the film but the role went to Bonham Carter.

Why it beats the 2017 miniseries

Look, the 2017 BBC/Starz miniseries was fine. Hayley Atwell is great. But it lacked the teeth of the 1992 version. The film has a certain cinematic density. Every frame is packed with detail. Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, who wrote the screenplay, was a master of subtext. She knew how to make a silence feel like a slap in the face.

The film Howards End 1992 doesn't over-explain things. It trusts you to understand the social cues. It trusts you to see the hypocrisy of the characters without a narrator pointing it out.

Actionable insights for your next watch

If you're going to revisit this classic, or watch it for the first time, don't just look at the pretty dresses. Look at the hands. James Ivory uses close-ups of hands—touching flowers, holding letters, gripping umbrellas—to show the characters' true feelings when their faces are forced to stay composed.

👉 See also: The Reality of Sex Movies From Africa: Censorship, Nollywood, and the Digital Underground

Check the background. In the London scenes, the city is always under construction. There’s always noise, smoke, and change. This is intentional. It shows the world the characters know is literally being torn down around them.

Pay attention to the music. Richard Robbins’ score is heavily influenced by Percy Grainger. It’s bouncy and light in the Schlegel scenes but becomes heavy and melancholic as the Wilcox influence takes over.

Watch it as a companion to The Remains of the Day. Also a Merchant Ivory production, also starring Hopkins and Thompson. It’s like a mirror image of Howards End. While Howards End is about trying to connect, The Remains of the Day is about the tragedy of never trying at all.

To truly appreciate the film, you have to accept that none of these people are perfect. Margaret is a hypocrite. Henry is a bigot. Helen is reckless. But in the hands of these actors, they are vibrantly, painfully human. That’s why we’re still talking about it thirty-four years later. It’s not a museum piece; it’s a living, breathing mirror of our own social messes.

If you want to dive deeper into the world of 90s prestige cinema, your next move is to track down the 4K restoration of the film. The colors in the meadow scenes are vastly superior to any old DVD or standard streaming version you might find. It changes the entire mood of the ending. After that, read Forster’s original 1910 text. You’ll be surprised at how much of the "modern" feeling in the movie actually came directly from a guy writing at the turn of the century.

Next Steps for the Film Enthusiast:

- Seek out the 4K Cohen Media Group restoration to see the true detail of the Oscar-winning production design.

- Compare the "Only Connect" speech in the book versus Thompson's delivery to see how she added a layer of desperation to the character's optimism.

- Watch the 1993 film The Remains of the Day immediately afterward to see the pinnacle of the Hopkins-Thompson-Ivory collaboration.