It started with a survey. In 1957, Betty Friedan went to her 15th college reunion at Smith and handed out a questionnaire to her former classmates. She expected to find a group of satisfied, educated women living the suburban dream. Instead, she found a ghost.

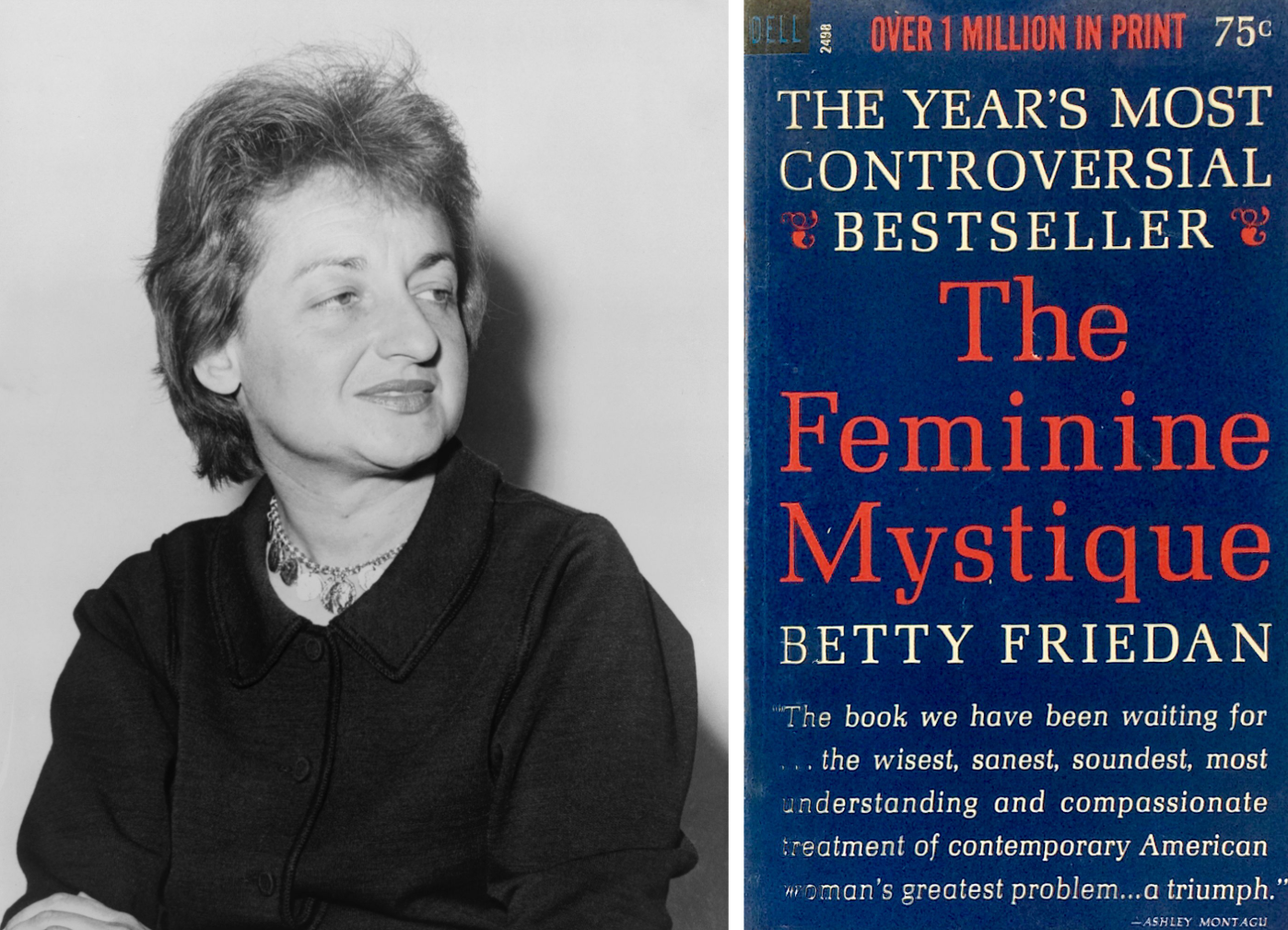

Everywhere she looked, women were struggling with a strange, gnawing emptiness. They had the suburban house. They had the husband with the steady corporate job. They had the station wagon and the three kids. Yet, they were miserable. Friedan called it "the problem that has no name." When she eventually published The Feminine Mystique by Betty Friedan in 1963, she didn't just write a book; she dropped a hand grenade into the American living room.

It’s hard to imagine now, but back then, women were told their entire identity was wrapped up in being a "professional" housewife. If you weren't happy vacuuming in heels, there was something wrong with you, not the system. Friedan looked at that and said, basically, "This is a lie."

The Lie of the Happy Housewife

The "mystique" wasn't some magical aura. It was a societal pressure cookers. It was the idea that women could find total fulfillment through housework, marriage, and children alone. Friedan argued that this image was being sold to women by magazines, advertisers, and even educators.

Think about the ads from the late 50s. They showed women beaming at their new washing machines as if the appliance were a long-lost child. Friedan's genius—or her controversy, depending on who you asked—was pointing out that these women were actually bored out of their minds. They were "comfortable concentration camps," as she famously (and very divisively) described the suburban home.

She noticed that the more women tried to fit the mold, the more they felt like they were disappearing. They were taking tranquilizers. They were visiting doctors for "tiredness" that no amount of sleep could fix. It wasn't physical exhaustion. It was intellectual starvation.

How The Feminine Mystique by Betty Friedan Changed the Narrative

Before the book hit the shelves, if a woman felt unfulfilled, her doctor might suggest she buy a new rug. Or maybe have another baby. Friedan shifted the blame from the individual woman to the culture.

She spent years researching how this happened. It wasn't an accident. After World War II, men came home and wanted their jobs back. The women who had been working in factories and offices during the war were told to go back to the kitchen. The media pivoted hard. Suddenly, the "modern" woman was one who stayed home.

💡 You might also like: Wire brush for cleaning: What most people get wrong about choosing the right bristles

Friedan’s book sold over three million copies in its first three years. That’s insane for a non-fiction book about sociology. It resonated because it gave women permission to admit they wanted more. They wanted careers. They wanted to use their brains for something other than deciding between different brands of floor wax.

Honestly, the book is dense. It’s not a light beach read. It’s packed with psychoanalytic theory and critiques of people like Sigmund Freud, whom Friedan blamed for cementing the idea that women were "naturally" passive. She tore into the idea of "penis envy," arguing that women didn't want to be men; they wanted the freedom men had to define themselves.

The Problem with the "Problem"

We have to be real here: the book had blind spots. Huge ones.

Friedan was writing for a very specific audience. She was writing for white, middle-class, educated women in the suburbs. If you were a Black woman working as a domestic servant in 1963, "the problem that has no name" sounded like a luxury. You were already working. You didn't have the "mystique" of the idle housewife because you couldn't afford it.

Bell Hooks and other later feminists pointed this out quite sharply. They argued that Friedan’s revolution was a bit narrow. It ignored the fact that for many women, the "right to work" wasn't a choice—it was a survival tactic. Friedan focused on the psychological prison of the suburb, but she didn't spend much time on the economic prison of poverty or the systemic walls of racism.

Why We Are Still Talking About It in 2026

You might think a book from the sixties is a relic. It’s not.

The "mystique" has just changed its outfit. Today, we have the "tradwife" trend on social media. We see influencers in pristine kitchens, wearing vintage dresses, telling millions of followers that true happiness is found in "submitting" to a husband and sourdough starters.

📖 Related: Images of Thanksgiving Holiday: What Most People Get Wrong

It feels like a glitch in the Matrix.

Friedan would likely have a heart attack if she saw a TikTok "Get Ready With Me" video where a 22-year-old argues that feminism ruined everything. The core struggle she identified—the tension between individual identity and societal expectations—is still very much alive. We’ve just traded the "Happy Housewife" for the "Girlboss" or the "Perfect Mother" who somehow works 60 hours a week and still packs bento boxes that look like art.

Pressure is still pressure.

The Backlash Was Immediate (and Loud)

People hated this book. I mean, they really hated it.

Critics called Friedan a "shrew." They said she was destroying the American family. Even some women felt attacked. They felt that if they were actually happy being stay-at-home moms, Friedan was telling them they were stupid or brainwashed.

But Friedan wasn't saying every woman must leave the home. She was saying every woman must have the choice to be a full human being. She argued that a woman who has a life of her own, interests of her own, and a sense of purpose is actually a better mother and a better wife because she isn't resenting her family for "stealing" her life.

A Few Surprising Facts About the Book

- The Title wasn't original: She almost called it "The Lotus-Eaters" or "The Togetherness Trap."

- It was a rejection project: She tried to sell the original article to magazines like McCall's, but they turned it down because it was too radical. She realized it had to be a book.

- Friedan wasn't just a housewife: Despite the image often painted of her, she was a professional journalist for years. She knew exactly how the media sausage was made.

Taking Action: What to Do With This Today

Reading The Feminine Mystique by Betty Friedan today isn't just a history lesson. It’s a diagnostic tool for your own life.

👉 See also: Why Everyone Is Still Obsessing Over Maybelline SuperStay Skin Tint

If you feel like you're performing a role instead of living a life, you're experiencing a version of the mystique. Whether it’s the pressure to be the perfect corporate climber or the perfect parent, the "role" is often a cage.

First, audit your influences. Look at the media you consume. Are you being sold an image of "happiness" that requires you to suppress your actual interests? Friedan’s biggest piece of advice was to engage in "creative work." This doesn't mean painting (though it could). It means work that challenges you and connects you to the world.

Second, stop the guilt. Friedan spent a lot of time talking about how guilt is used as a tool for control. If you're doing something for yourself—going back to school, starting a side hustle, or just taking a weekend away—and you feel guilty, ask yourself: "Who told me I should feel this way?"

Third, recognize the "naming" power. The reason the book worked is because it gave a name to a feeling. If you’re struggling with something, name it. Talk about it. Isolation is the mystique's best friend. Once women started talking to each other in 1963, the walls started coming down.

The book wasn't the end of the story. It was the starting gun. It led directly to the founding of NOW (National Organization for Women) and the second wave of feminism. It reminds us that "normal" is often just a social construct, and we have the right to change it if it doesn't fit.

To really move forward, look for the gaps in Friedan's logic. Acknowledge that her version of freedom was incomplete. True liberation isn't just for the woman in the big house; it’s for everyone. Use the book as a lens to see where we’ve come and, more importantly, where we still need to go. If you find yourself feeling that "problem that has no name," remember that you aren't crazy—you're probably just ready for a change.