It happened in a blur. If you blinked, you literally missed it. In the summer of 2023, at a Rubik’s WCA North American Championship, a young man named Max Park sat down, breathed, and changed the history of cubing forever. He solved a standard 3x3x3 cube in 3.13 seconds.

3.13.

Think about that for a second. In the time it takes you to inhale a single breath, he processed the scrambled state of 54 colored stickers, executed dozens of finger movements, and slammed the cube onto the timer. It’s a feat of human processing that seems almost alien. For years, the community wondered if we were hitting a physical wall. We weren't. Honestly, the fastest time to solve a rubik's cube isn't just about fast fingers; it’s about a weird, beautiful intersection of group-think, advanced mathematics, and a piece of plastic that costs about thirty bucks.

Breaking the Three-Second Barrier: Is it Even Possible?

People used to think sub-five seconds was the absolute limit. Then Yusheng Du shocked the world with a 3.47 in 2018. That record stood for years. It felt untouchable, like a glitch in the matrix that nobody could replicate. But the thing about speedcubing is that the "ceiling" is usually just a lack of better hardware or a more efficient look-ahead strategy.

Max Park’s 3.13-second world record didn't come out of nowhere. Max is a legend in the community, especially known for his dominance in larger cubes like the 4x4, 5x5, and 6x6. His 3x3 record was a long time coming. The crazy part? The mathematical "God’s Number"—the maximum number of moves required to solve any cube—is 20. Most speedcubers use about 50 to 60 moves. When you see a 3-second solve, you’re watching someone perform roughly 10 to 12 moves per second.

It’s called TPS, or turns per second. But high TPS is useless if you have to stop and think. If you pause for even a tenth of a second to look for your next pair of pieces, the record is gone. You’ve lost. You have to see the future.

How the Fastest Time to Solve a Rubik's Cube Actually Happens

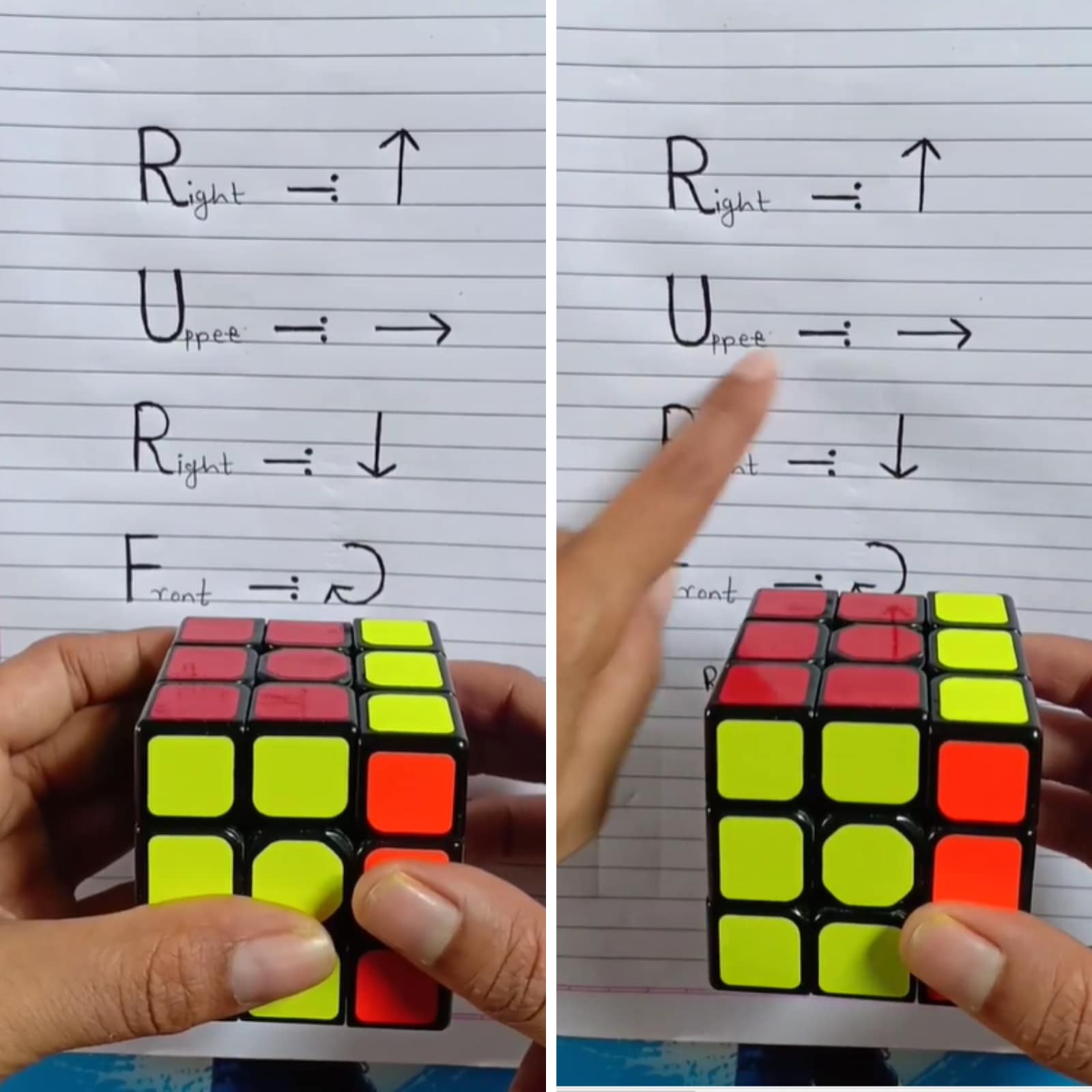

You’ve probably heard of the CFOP method. It stands for Cross, F2L (First Two Layers), OLL (Orientation of the Last Layer), and PLL (Permutation of the Last Layer).

👉 See also: LeBron James and Kobe Bryant: What Really Happened Behind the Scenes

Almost every world record in the last decade has used this system. But here’s what most people get wrong: they think the record-holders are just doing CFOP faster than everyone else. They aren't. They’re using "pseudo-slotting," "X-crosses," and "ZBLL."

ZBLL is a beast. It’s an extension of the solve where you recognize the entire last layer’s state and solve it in one single algorithm instead of two. There are nearly 500 different ZBLL cases. Top-tier cubers like Max Park or Yiheng Wang (a child prodigy from China who is currently obliterating averages) have memorized hundreds of these sequences. They see a specific pattern of stickers and their hands move reflexively. There is no "thinking" involved. It is pure muscle memory.

The Hardware Arms Race

You can't break a world record on a cube you bought at a pharmacy. You just can't. Those old-school cubes use friction-heavy plastic and internal designs that lock up if you aren't perfectly aligned.

Modern speedcubes are engineering marvels. They have:

- Magnetic Core Systems: Tiny magnets in the pieces that "snap" the layers into place, preventing over-turning.

- MagLev Technology: Replacing traditional springs with repelling magnets to reduce friction to near zero.

- Corner Cutting: The ability for the cube to turn even if the top layer is misaligned by 45 degrees.

Brands like Gan, MoYu, and QiYi are the Ferraris of the cubing world. When you’re chasing the fastest time to solve a rubik's cube, the difference between a $10 cube and a $90 flagship cube is everything. If the cube catches or pops during a world-record pace solve, that's years of practice down the drain.

The Rise of the "Averages"

While the single-solve world record gets the headlines, the cubing community actually respects the "Average of 5" more. In a WCA (World Cube Association) competition, you get five turns. They throw out the fastest and slowest times and average the middle three.

✨ Don't miss: Lawrence County High School Football: Why Friday Nights in Louisa Still Hit Different

This is where things get truly terrifying.

Yiheng Wang has been setting "Average of 5" records that hover around the 4.4-second mark. Think about the consistency required for that. It’s one thing to get a "lucky" scramble—where the pieces happen to fall into place—and hit a 3-second single. It’s another thing entirely to solve the cube five times in a row and have the average stay under 5 seconds. That requires a level of "look-ahead" where you are tracking the position of pieces for your next step while your fingers are still finishing the current step.

Luck vs. Skill: The "Lucky Scramble" Debate

Is the fastest time to solve a rubik's cube just luck? Sorta. But also, no.

Every scramble in a competition is generated by a computer to ensure it requires at least a certain number of moves. However, some scrambles are "solvable" in a way that aligns better with human ergonomics. If a scramble allows for an "easy" X-cross (solving the bottom cross and the first pair of corner/edges simultaneously), a professional will capitalize on it.

Max Park’s 3.13 solve was an incredibly efficient solution, but he still had to execute it under the pressure of hundreds of people watching and a ticking clock. If you or I were given that same "lucky" scramble, we’d still take a minute. The "luck" only matters when you have the god-tier skill to exploit it.

The Psychology of the Solve

Most people don't realize that cubing is a mental game. You get 15 seconds of inspection time. During those 15 seconds, a pro isn't just looking for the first four pieces. They are mentally mapping out the first 10 to 15 moves.

🔗 Read more: LA Rams Home Game Schedule: What Most People Get Wrong

They close their eyes and can "see" where the pieces will end up after the first few turns. This is why you see them start the solve with such explosive speed. They aren't reacting to the cube; they are executing a pre-planned script.

The pressure is immense. Your hands shake. "Comp shakes" are a real thing in the cubing world. Your heart rate spikes, your fine motor skills degrade, and suddenly that 3-second solve becomes a 7-second disaster. Max Park is famous for his calm. His ability to stay "in the zone" is arguably his greatest strength, even more than his TPS.

What's Next for the Record?

We are approaching the physical limits of human reaction time. To go much faster than 3 seconds, you need a scramble that is statistically improbable—something with a 4 or 5-move cross and a "skip" (where a layer is already solved).

But don't bet against the kids. Every year, a new 10-year-old appears on the scene with faster fingers and a better understanding of ZBLL than the generation before them. The fastest time to solve a rubik's cube will likely drop into the 2-second range eventually. It sounds impossible, but so did sub-4.

How to Actually Get Faster

If you're stuck at 30 seconds or a minute, don't worry about world records yet. Focus on these specific shifts:

- Stop Rotating: Every time you tilt the whole cube to see the back, you lose half a second. Learn to use "U" moves to bring pieces to you.

- Slow Down to Go Fast: It sounds counterintuitive, but if you turn slightly slower, you can see the pieces moving. This prevents pauses. A slow solve with no pauses is always faster than a fast solve with three "stop-and-think" moments.

- Master Finger Tricks: Stop using your whole hand to turn a face. Use your index fingers for top turns and your ring fingers for bottom turns.

- Learn F2L Properly: Don't just memorize algorithms. Understand how the pieces move. This is the "intuition" phase that separates the casuals from the speedcubers.

The journey from a one-minute solve to a ten-second solve is a long road of muscle memory and pattern recognition. It’s frustrating. It’s tedious. But when you finally hit that flow state where your hands move faster than your brain can keep up with, you'll understand why people like Max Park spend thousands of hours chasing a fraction of a second.

The cube is a puzzle, but speedcubing is a sport. And in this sport, the finish line is always moving.

Actionable Next Steps for Aspiring Speedcubers

- Record your solves: You can't fix what you don't see. Film your hands to see where you are wasting movement or "regripping" the cube unnecessarily.

- Use a dedicated timer app: Apps like CSTimer or Twisty Timer provide professional scrambles and track your "Average of 5" and "Average of 12," which are better metrics of progress than single fast solves.

- Upgrade your hardware: If you are still using a non-magnetic cube, buy a budget magnetic speedcube like the MoYu RS3M. It’s a game-changer for under $15.

- Join the community: Check the World Cube Association (WCA) website for competitions near you. Even if you're slow, the atmosphere is incredibly welcoming and you'll learn more in one afternoon than in a month of YouTube tutorials.