Jacques Tardi didn't want a hero. He wanted a mess. When he first started sketching the world of late 19th-century Paris, he wasn't looking for a caped crusader or a flawless detective. He found Adèle. She's grumpy. She smokes too much. She has a temper that could peel paint off a wall. Honestly, The Extraordinary Adventures of Adèle Blanc-Sec is probably one of the most honest depictions of a "protagonist" ever put to paper, despite the fact that she spends her time dealing with resurrected mummies and Jurassic-era pterodactyls.

It’s weird. It’s gritty. It’s quintessentially French.

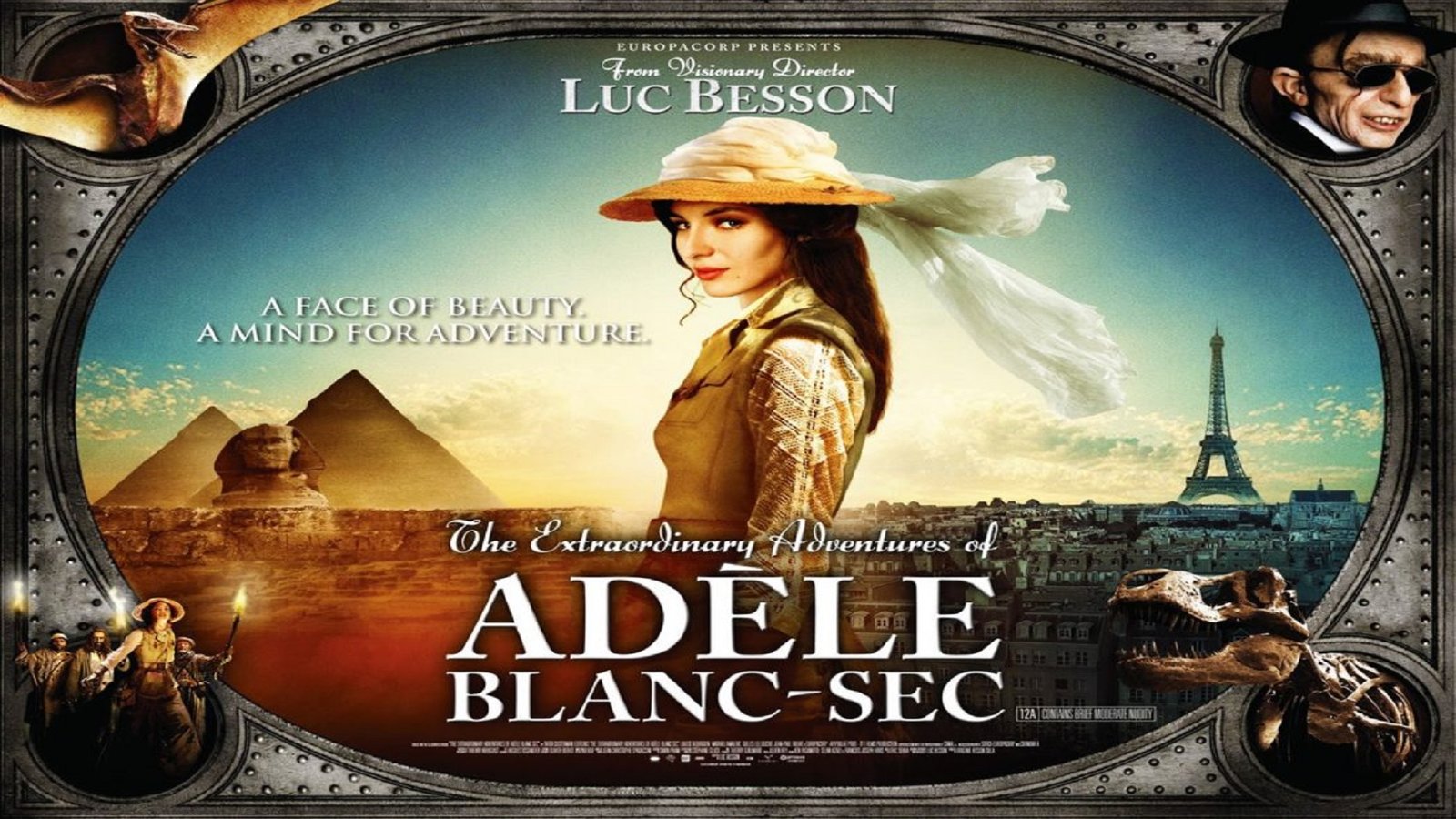

If you’ve only seen the 2010 Luc Besson film, you’ve basically seen the "Disneyfied" version of a much darker, much more cynical masterpiece. Tardi’s original vision, which debuted in 1976, wasn't just about pulp adventure; it was a scathing critique of the French elite, the military, and the general incompetence of people in power. Adèle isn't trying to save the world. She’s usually just trying to get paid or survive the sheer stupidity of the bureaucrats surrounding her.

The Pterodactyl in the Room

Most people start their journey with The Extraordinary Adventures of Adèle Blanc-Sec through the first volume, Adèle et la Bête. It’s 1911. Paris is waking up to a nightmare. An egg in the Jardin des Plantes, millions of years old, hatches. A prehistoric bird starts snatching up citizens. It sounds like a B-movie plot because, well, Tardi loved B-movies. But the way he draws it is different.

His lines are heavy. The soot of Paris practically rubs off the page onto your fingers.

Tardi’s "Ligne Claire" style is often compared to Hergé’s Tintin, but while Tintin is clean and moralistic, Adèle is muddy. She operates in a gray area. In the first few stories, she’s actually a novelist—though some might call her a plagiarist or a con artist depending on the day. She gets caught up in the pterodactyl incident not because she wants to be a hero, but because she’s investigating a lead for her own gain. This subversion of the "plucky reporter" trope is exactly why the series survived the 70s and became a cult classic.

💡 You might also like: Kiss My Eyes and Lay Me to Sleep: The Dark Folklore of a Viral Lullaby

Why Tardi Broke the Rules of Fiction

You have to understand the context of the Franco-Belgian comic scene in the 1970s. Everything was very structured. You had your heroes, your villains, and a clear moral lesson at the end. Tardi looked at that and decided to do the opposite. He populated his world with characters who have hideous noses, terrible teeth, and even worse personalities.

Look at Inspector Caponi. He’s the quintessential bumbling cop. But he’s not "cute" bumbling. He’s frustratingly incompetent in a way that feels dangerously real. Tardi uses the supernatural elements—the mummies, the monsters, the mad scientists—as a backdrop to highlight how poorly humans handle crises. In The Extraordinary Adventures of Adèle Blanc-Sec, the real monsters are usually the ones wearing medals on their chests or sitting behind a government desk.

Adèle herself is a bit of an enigma. She’s cynical because she has to be. In a pre-WWI society that viewed women as decorative or secondary, Adèle simply refused to play the game. She wears men’s clothes when it’s practical. She stares down monsters with a look of utter boredom. She’s tired. You can see it in her eyes. It’s a level of character depth you just didn't see in "fun" adventure comics back then.

The 1910s: A World on the Brink

The setting isn't just a choice; it's a character. Tardi is obsessed with the period leading up to the Great War. This isn't the "Belle Époque" of postcards and romance. This is the Paris of deep shadows, anarchists, and crumbling infrastructure. By placing Adèle in this specific timeframe, Tardi creates a sense of impending doom that the reader knows is coming, even if the characters don't.

One of the most striking things about The Extraordinary Adventures of Adèle Blanc-Sec is how it handles the transition of time. The series spans years. Characters age. Some die. Some just disappear.

📖 Related: Kate Moss Family Guy: What Most People Get Wrong About That Cutaway

Key Volumes You Need to Track Down:

- Pterodactyls and Mummies: The early stuff. This is where the world-building is at its peak.

- The Mad Scientist Arc: Tardi leans hard into the "savants fous" trope here, but with a dark twist.

- The Post-War Shift: Without spoiling too much, the way the series handles the gap created by WWI is heartbreaking and brilliant.

The narrative isn't linear in the way a modern TV show is. It’s sprawling. Characters from Volume 1 might pop up in Volume 5 only to be killed off in a freak accident. It’s chaotic. It’s life.

The Luc Besson Adaptation: A Different Beast

We have to talk about the movie. Louise Bourgoin did a fantastic job capturing Adèle’s sass, and the visual effects were top-tier for 2010. But the film merges several books into one "adventure" and strips away a lot of the political bite. It leans into the Amélie aesthetic—whimsical, bright, slightly magical.

Tardi’s books aren't whimsical. They are heavy.

If you’ve only seen the film, you’re missing the sheer nihilism of the comics. In the books, Adèle’s "adventures" often end in failure or hollow victories. There’s a scene in the comics where mummies are walking around Paris, and instead of a grand climax, they mostly just stand around being confused by modern life. It’s absurdism at its finest. Tardi is mocking the very idea of a "grand adventure."

Breaking Down the Art Style

Tardi uses a style called le réalisme documentaire. He spends hours researching the exact architecture of the bridges, the specific uniforms of the Parisian police, and the labels on the wine bottles. This hyper-accuracy in the background makes the bizarre elements—like a demon-worshipping cult in the sewers—feel terrifyingly plausible.

👉 See also: Blink-182 Mark Hoppus: What Most People Get Wrong About His 2026 Comeback

His use of "silence" is also legendary. Sometimes you'll get a full page of Adèle just walking through a rainy street. No dialogue. No narration. Just the atmosphere. It builds a sense of loneliness that defines the character. She is a woman out of time, fighting a world that doesn't want her to exist.

The Legacy of Adèle

Why does she still matter in 2026? Because we’re still dealing with the same stuff. Incompetent leaders? Check. A sense of impending global dread? Check. The feeling that you’re the only sane person in a room full of idiots? That’s Adèle’s entire brand.

She paved the way for modern "difficult" female protagonists. Before there was Fleabag or Jessica Jones, there was Adèle Blanc-Sec. She proved that a woman could lead a series without needing to be "likable." She didn't need a love interest. She didn't need a tragic backstory involving a lost child to justify her being "tough." She was just tough because that’s who she was.

How to Experience Adèle Today

- Start with the Fantagraphics Collections: They’ve done an incredible job translating and restoring the original colors. The oversized hardcovers are the best way to see Tardi’s detail.

- Read them in order: While some stories stand alone, the background "conspiracy" builds over time. You’ll miss the payoff of the mummies if you skip ahead.

- Look past the monsters: Focus on the people in the background. Tardi puts a lot of Easter eggs in the crowd scenes—real historical figures, references to other French literature, and jokes about the art world of the time.

- Embrace the confusion: Sometimes the plot gets dense. It’s okay. The vibe is more important than the specific mechanics of the "ancient curse" of the week.

The real "extraordinary" part of The Extraordinary Adventures of Adèle Blanc-Sec isn't the magic. It’s the fact that in a world of monsters, a cynical woman with a cigarette and a sharp tongue is the most interesting thing on the page.

If you’re looking for a series that respects your intelligence and doesn't sugarcoat the world, this is it. Go find a copy of The Pterodactyl of the Eiffel Tower. Put on some dark jazz. Set your expectations for "weird" to maximum. You won't regret it.

The best way to appreciate Tardi's work is to look at it as a historical document of a world that never was, but feels like it should have been. It’s a masterclass in atmosphere. It’s a lesson in how to write a character who doesn't care if you like her. In a world of polished, focus-grouped entertainment, Adèle remains gloriously, wonderfully jagged.