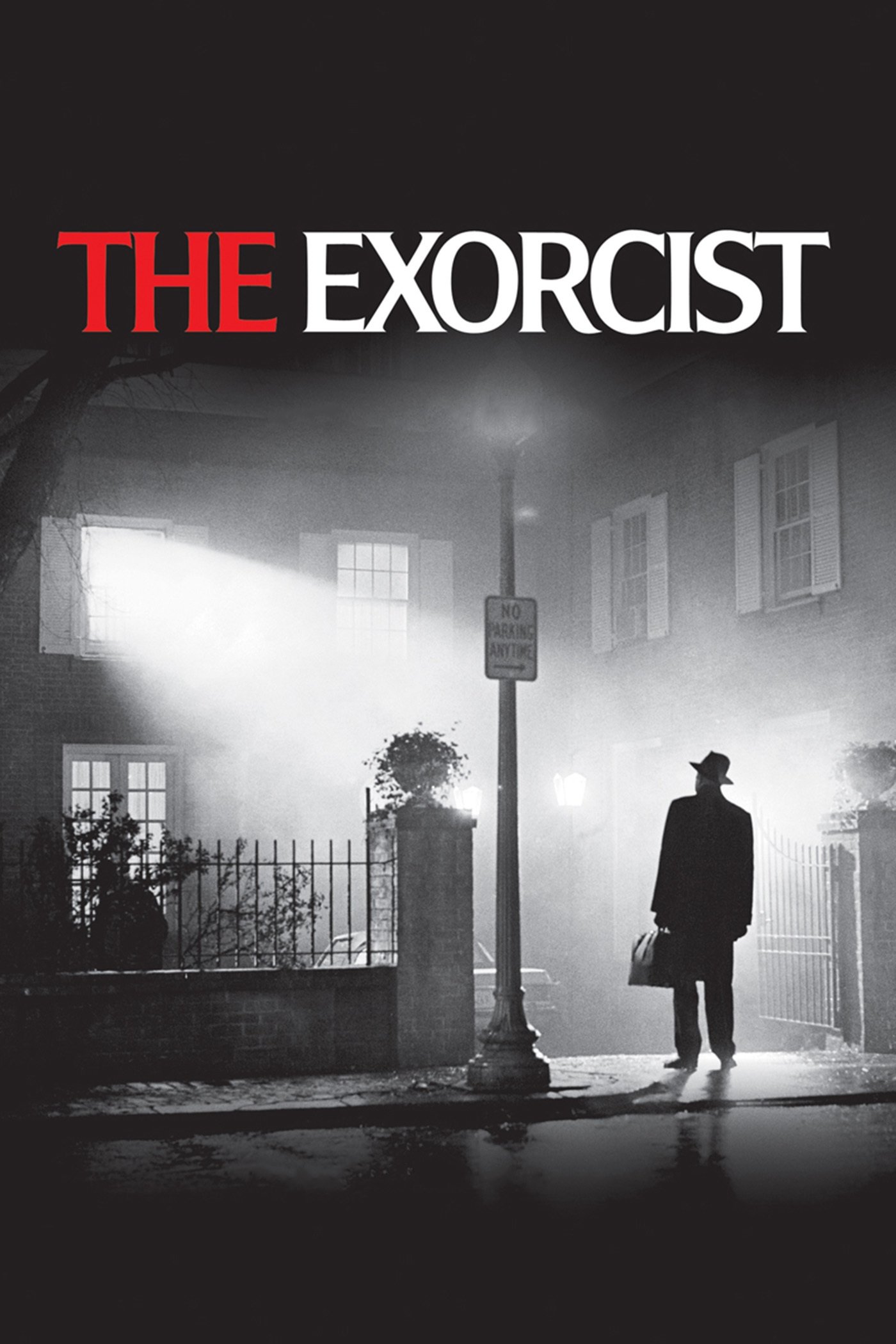

It is a grainy, black-and-white shot of a man standing under a streetlamp. Fog rolls in, thick as pea soup. He’s wearing a hat, carrying a briefcase, and staring up at a brownstone window where a violent, unnatural light spills out into the Georgetown night. You’ve seen it. Even if you haven’t watched the movie in a decade, that specific The Exorcist movie images composition is burned into your brain. It’s iconic. It’s also deeply deceptive because it promises a quiet, noir-style mystery before the film descends into some of the most visceral, repulsive, and religiously provocative imagery ever captured on 35mm film.

William Friedkin didn’t just want to scare people; he wanted to assault them.

When we talk about the visual legacy of this 1973 masterpiece, we aren't just talking about a girl with a rotating head. We’re talking about the subconscious. We're talking about the "Subliminal Demon" flashes that lasted for only a fraction of a second—frames of a white-faced entity (played by Eileen Dietz) that caused theater-goers in the seventies to literally vomit in the aisles. That isn't hyperbole. There are dozens of documented accounts of fainting and nausea from the original theatrical run. The imagery was so potent it felt dangerous.

The shadow of the hat: Composition and the "Iconic" shot

Most people think the famous poster image—the priest arriving at the house—is a clever studio setup. It’s actually based on a painting. Specifically, René Magritte’s Empire of Light. Friedkin was obsessed with the idea of day and night existing in the same space. That’s why that image works. It feels "off" in a way you can't quite put your finger on until you really look at the lighting.

The man in the photo, Max von Sydow, was only 44 years old when they filmed that. Look closely at the production stills. The makeup artist, Dick Smith, spent hours every morning turning a middle-aged Swedish actor into the octogenarian Father Merrin. The texture of the skin in those close-up The Exorcist movie images is a masterclass in practical effects. It’s latex and pros-aide, layered so thinly it looks like genuine, parchment-thin elder skin. Modern CGI can't touch that level of tactile reality because your brain knows when it's looking at pixels versus actual physical material reacting to light.

The bedroom scenes: A nightmare in blue and grey

Once you get inside the MacNeil residence, the color palette shifts. It’s cold. Friedkin actually built the bedroom set inside a giant freezer. That’s not a special effect. When you see the breath of Jason Miller (Father Karras) or Linda Blair, that’s real condensation. It gives the images a crisp, biting quality. You can almost feel the chill coming off the screen.

👉 See also: When Was Kai Cenat Born? What You Didn't Know About His Early Life

The physical transformation of Regan MacNeil is where the visual horror peaks. It starts subtly. A bit of puffiness. A greyish tint to the skin. Then come the self-inflicted wounds. The "Help Me" writing appearing on her stomach was achieved using a foam latex skin over a fiberglass torso, with a heating element underneath that caused the "welts" to rise. It’s a gruesome, intimate kind of body horror that feels violates the sanctity of childhood.

Honestly, the most disturbing The Exorcist movie images aren't even the ones with the blood. It’s the medical scenes. The arteriogram sequence is famously difficult to watch. It’s shot like a documentary. The needles, the blood spurting into the tubes, the cold mechanical sounds—it grounds the supernatural in a terrifyingly sterile reality. Friedkin’s background in documentary filmmaking shows here. He knew that if the audience believed the hospital scenes, they would believe the devil.

The face of Pazuzu: Those blink-and-you-miss-it frames

Let's talk about Captain Howdy. That's the name Regan gives her "imaginary friend." In the original cut, we see flashes of a death-mask-like face. These images were never meant to be lingered on. They were intended to bypass the conscious mind and trigger a primal "fight or flight" response.

- The first flash happens during the medical exams.

- The second occurs in the kitchen, reflected for a split second.

- The third is during the actual exorcism.

These frames are often over-analyzed now because of the "pause" button on our remotes. But in 1973? You didn't have a pause button. You just had a sense that you saw something horrific, but you weren't sure what. That’s the power of the visual language here. It plays with the persistence of vision.

Why we can't look away from the gore

Dick Smith's work on this film changed the industry. Before this, movie gore was often bright red "stage blood" that looked like syrup. Smith pioneered the use of varying viscosities. The "pea soup" vomit (which was actually Andersen’s Pea Soup mixed with a little oatmeal) was rigged to a hidden tube on Linda Blair’s chin. The image of that green spray hitting the priest’s face is a cornerstone of horror history.

✨ Don't miss: Anjelica Huston in The Addams Family: What You Didn't Know About Morticia

But look at the eyes. That’s the real secret to why the The Exorcist movie images remain so effective. They used custom-painted contact lenses for Linda Blair. They weren't just "scary" eyes; they were cat-like, yellowed, and devoid of human empathy. When the camera pushes in for a close-up, you aren't looking at a little girl anymore. You’re looking at a void.

The levitation scene is another one that holds up. No wires are visible because they used a mechanical "cradle" hidden by the bed and the girl's clothing. This allowed for a physical weightiness that CGI often lacks. When she floats, there is a physical tension in the room that the camera captures perfectly.

The Georgetown stairs and the "Spider Walk"

The "Spider Walk" image is perhaps the most famous "lost" visual of the film. For decades, it was just a legend. A few grainy production photos existed in magazines, showing Regan contorted backward, scuttling down the stairs. Friedkin originally cut it because he felt it happened too early in the movie and "broke the tension."

When it was finally restored in the 2000 "Version You've Never Seen," it divided fans. Some thought it was too much. Others felt it completed the visual puzzle. The image of the girl's mouth filling with blood as she reaches the bottom of the stairs is a jarring, unnatural sight that stays with you. It’s a reminder that the demon isn't just a spirit; it’s a physical intruder.

The actual stairs in Georgetown are still a tourist site. They are steep, narrow, and made of cold stone. The cinematography during Father Karras’s final fall captures the sheer verticality of that location. The way the camera tracks his body tumbling down—it feels final. It feels heavy.

🔗 Read more: Isaiah Washington Movies and Shows: Why the Star Still Matters

Lessons for modern creators and fans

If you're looking at these images today, whether for a film project or just because you’re a horror buff, there’s a lot to learn about restraint. Modern horror often shows too much, too soon. The Exorcist builds its visual vocabulary slowly.

- Focus on texture. The sweat on the priests' foreheads, the peeling wallpaper, the frost on the breath. These things matter more than big explosions.

- Use lighting to tell the story. Notice how the lighting gets harsher and more "unnatural" as the possession progresses.

- Don't fear the quiet. Some of the most haunting images in the film are just of a hallway or an empty chair.

How to explore the visual history further

If you want to dive deeper into the world of The Exorcist movie images, you shouldn't just look at Google Images. You need to look at the process.

Start by finding a copy of The Exorcist: Out of the Shadows or the 40th-anniversary Blu-ray behind-the-scenes footage. Seeing the mechanical rigs used to shake the bed or the way the makeup was applied reveals the sheer amount of human labor involved in these scares.

You can also visit the actual filming locations in Washington D.C. Standing at the bottom of the "Exorcist Steps" at 36th and Prospect St NW gives you a perspective on the cinematography that no screen can provide. You realize just how much the camera cheated the angles to make that drop look even more lethal than it already is.

Check out the work of Owen Roizman, the cinematographer. His use of "low-key" lighting influenced an entire generation of thrillers. He didn't use a lot of fancy filters. He just knew how to place a light to create a deep, impenetrable shadow. That shadow is where the fear lives.

To really appreciate the craft, try watching the film on a high-quality 4K restoration. You’ll see the grain. You’ll see the imperfections. And ironically, those imperfections make the horror feel more real. It doesn't look like a "movie." It looks like a window into a very dark room that we probably shouldn't be looking into.

Pick up a copy of the screenplay and compare the descriptions to the final frames. You'll see how a few lines of text became some of the most analyzed images in cinema history. It’s a testament to the fact that while words can describe a demon, it takes a truly gifted eye to show you one.