Trains aren't just for commuting. Honestly, if you've ever stood on the platform at Chicago’s Union Station and watched the double-decker Superliner cars of the Empire Builder Great Northern service roll in, you know it's something else entirely. It’s big. It’s silver. It feels like a time machine that somehow survived the jet age.

James J. Hill was the guy behind the curtain here. Known as the "Empire Builder," he didn't just want to move freight; he wanted to settle the American Northwest. He pushed the Great Northern Railway across the "High Line" of Montana and North Dakota, navigating some of the most brutal geography in the lower 48. Today, Amtrak runs the service that bears his nickname, and it remains the busiest long-distance route in the national network for a reason.

It’s about the scale of it. You start in the urban sprawl of the Midwest and end up looking at the Pacific Ocean. Between those two points, you’re basically crossing a continent at a speed that actually allows your brain to process the change in landscape. It’s slow travel. It’s real.

The High Line and the Legacy of James J. Hill

James J. Hill was a different breed of railroad tycoon. Unlike many of his contemporaries who relied on massive federal land grants to fund their tracks, Hill built the Great Northern Railway primarily on private capital. He was obsessed with grades—the steepness of the climbs. He knew that every extra degree of incline meant more coal burned and fewer cars pulled. Because of this, the Empire Builder Great Northern route follows a path that is remarkably efficient, even as it scales the Continental Divide at Marias Pass.

Marias Pass is the lowest rail crossing of the Rockies in the United States. It’s only 5,213 feet up. That sounds high until you compare it to other mountain passes that force trains to crawl. Hill’s engineers found a way through the wilderness that allowed the Great Northern to beat the competition on speed and cost for decades.

The name "Empire Builder" was officially bestowed upon the premier passenger train in 1929. It was a marketing masterstroke. It promised passengers a glimpse into the "Empire" Hill had built—the wheat fields of the Dakotas, the cattle ranches of Montana, and the timber empires of the Pacific Northwest. Even today, when you look out the window of the Sightseer Lounge, you see that legacy. You see the grain elevators standing like sentinels in towns with populations smaller than the passenger manifest of the train you're riding.

What the Empire Builder Great Northern Experience is Actually Like

If you’re expecting a high-speed rail experience like the Shinkansen in Japan, you’re going to be disappointed. That’s not what this is. This is a 2,205-mile journey that takes about 46 hours if everything goes right.

And things don't always go right. Freight trains owned by BNSF often get priority, which can lead to "waiting in the hole" on a siding while a two-mile-long line of shipping containers rumbles past. It’s part of the rhythm.

👉 See also: Why the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum is the Coolest Place in NYC You Haven't Visited Yet

The Route Split: Portland vs. Seattle

One of the weirdest parts of the journey happens in Spokane, Washington. It usually happens in the middle of the night, around 2:00 AM. The train literally splits in half.

One section heads southwest toward Portland, Oregon, following the Columbia River Gorge. The other section continues west across the Cascade Mountains to Seattle. If you’re a scenery junkie, the Portland leg is often cited as the winner because of the sheer cliffs and waterfalls of the gorge, but the Seattle leg offers the incredible experience of the Stevens Pass and the 7.8-mile-long Cascade Tunnel.

Sleeping and Eating on the Rails

You have two choices: Coach or a Sleeper.

Coach is surprisingly comfortable. The seats are huge—bigger than first class on a domestic flight—and they recline deeply with leg rests. People spend two nights in these seats. It’s a bit like a giant, moving sleepover with strangers.

Then there are the Roomettes and Bedrooms. These are tiny. They are masterpieces of spatial engineering where a sofa turns into a bed and a bunk drops from the ceiling. If you’re in a sleeper, your meals are included. We’re talking actual dining car service with white tablecloths and real silverware. The "Signature Steak" is a thing people actually look forward to.

Why Glacier National Park is the Heart of the Trip

You can’t talk about the Empire Builder Great Northern without talking about Glacier National Park. The railroad basically invented the park’s tourism industry. To convince people to ride the train, the Great Northern Railway built massive, rustic lodges like the Glacier Park Lodge and the Many Glacier Hotel. They marketed the area as the "American Alps."

The train stops right at the park's entrance in East Glacier and West Glacier. In the summer, National Park Service volunteers often board the train between Shelby and Minot to give "Trails on Rails" presentations. They point out the wildlife and explain the geology of the Rocky Mountains while you roll past.

Marias Pass is the highlight here. As the train snakes along the southern edge of the park, you’re looking up at peaks that still hold glaciers. You see the Flathead River, crystal clear and turquoise, rushing alongside the tracks. It is, without exaggeration, some of the most beautiful terrain in North America accessible by public transit.

The Reality of Modern Rail Travel in the U.S.

Let’s be real for a second: Amtrak’s long-distance service is always under political fire. Critics point to the subsidies required to keep these routes running. However, for many communities along the High Line, the Empire Builder Great Northern is the only form of intercity transportation available. In the dead of a North Dakota winter, when the interstates are iced over and the small regional airports are closed, the train still rolls.

It’s a lifeline for places like Wolf Point, Montana, or Rugby, North Dakota (the geographical center of North America).

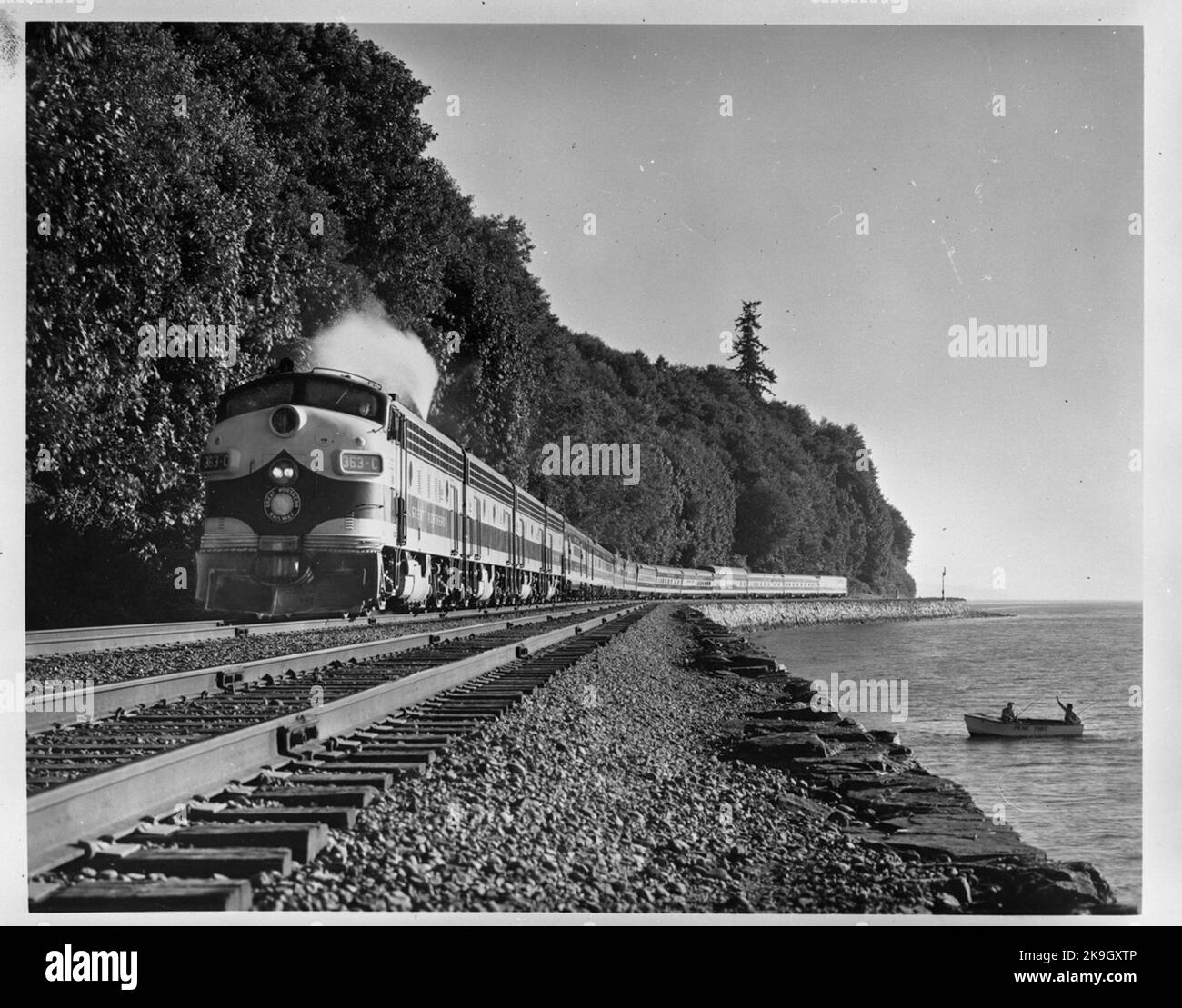

There’s also the "railfan" culture. You’ll see them at every crossing—people with scanners and high-end cameras waiting for that specific shot of the engine. There is a deep, abiding affection for this specific route because it represents a version of America that hasn't been completely homogenized by strip malls and exit-ramp fast food. You’re seeing the "backyard" of the country.

👉 See also: Newport Oregon Surf Forecast: Why Agate Beach Isn't Always the Answer

Logistics for the Modern Traveler

Planning a trip on the Empire Builder requires a bit of strategy.

- Eastbound vs. Westbound: Most veterans suggest going westbound (Chicago to Seattle/Portland). The timing usually works out better for seeing the best scenery in daylight, especially the trek through the Rockies.

- Booking Early: Prices for sleepers function like airline tickets—they go up as the train fills. Booking six months out can save you hundreds.

- The Sightseer Lounge: This is the car with windows that wrap up into the ceiling. It’s open to everyone. It’s the social hub. If you want a seat during the pass through Glacier, get there early.

- Fresh Air Stops: The train makes "smoke stops" every few hours. These are 10-15 minute windows where you can step off the train, stretch your legs, and breathe non-recycled air. Havre, Montana, and Minot, North Dakota, are the big ones.

Misconceptions About the Route

People think it’s boring. They look at a map of the Great Plains and assume they’ll be staring at "nothing" for 24 hours.

They're wrong.

The "nothingness" is actually a complex tapestry of agriculture and sky. The Big Sky Country of Montana is real; the horizon seems to drop away, and you feel the curve of the earth. Watching a sunset over the prairie from the back of a train is a meditative experience that you just can’t get at 35,000 feet.

Another myth is that it’s always late. While freight interference is real, Amtrak has worked hard to improve the "on-time" performance of the Builder. Is it perfect? No. But the delay is usually just more time to enjoy the lounge car.

Actionable Steps for Your Journey

If you’re ready to see the Empire Builder Great Northern route for yourself, don’t just wing it. Start by downloading the Amtrak app to track the train’s actual performance for a week before you go; it gives you a feel for the rhythm of the delays. Pack a power strip because older Superliner cars are notorious for having only one outlet per cabin.

Most importantly, bring a physical map. Cell service is non-existent for huge chunks of the trek through the mountains and the plains. Being able to look at a paper map and identify the river you’re following or the mountain peak in the distance adds a layer of connection to the landscape that Google Maps simply can’t provide when you’re out of range.

Book a roomette if you can afford the splurge. Having your own private space to watch the world go by, with coffee delivered to your door in the morning, is the closest you’ll get to the golden age of travel in the 21st century. It isn't just a commute; it is the destination. Grab a timetable, check the weather in Whitefish, and get on board.

Next Steps for Planning:

- Check the Amtrak "Vacations" site for package deals that include hotel stays in Glacier National Park.

- Visit the Great Northern Railway Historical Society website to see vintage photos of the original 1929 equipment.

- Use a rail-tracking tool like "ASM Transit Docs" to see the real-time location and history of Train 7 (Westbound) and Train 8 (Eastbound).