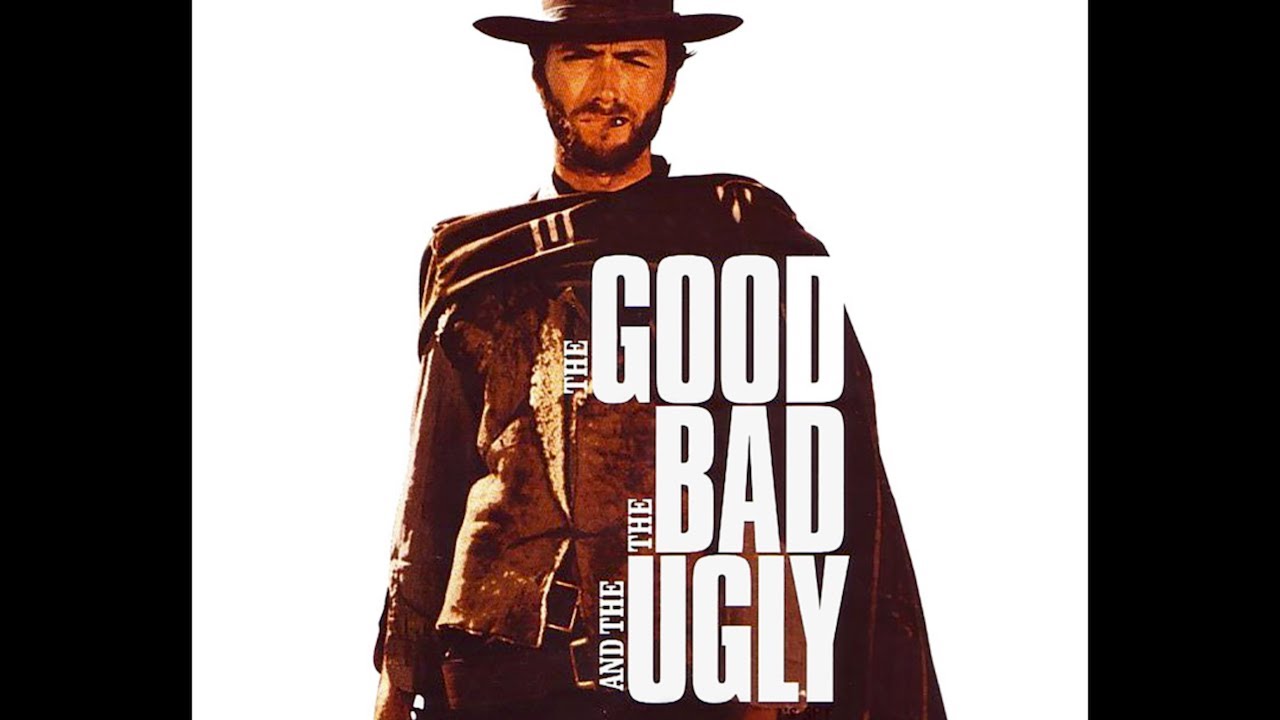

It starts with a piano. Just a few notes, lonely and urgent, like someone tapping on a window in the middle of a desert. Then comes the "wah-wah" of the harmonica, that signature Ennio Morricone sound that feels like sunbaked dirt and desperation. Most people know it as the theme from the end of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, but call it what it really is: The Ecstasy of Gold song is a masterclass in how to build tension until a human being feels like they’re going to explode.

You’ve probably heard it at a Metallica concert. They’ve used it as their intro music since 1983. You might have heard it in a Nike commercial or a Jay-Z track. But to really get why this piece of music sits in the Hall of Fame of human achievement, you have to look at what was happening on screen in 1966. Eli Wallach, playing Tuco, is sprinting through a massive, circular cemetery called Sad Hill. He’s looking for a grave. Not just any grave, but one containing $200,000 in Confederate gold.

The camera starts spinning. Tuco starts running. And Morricone’s music starts climbing a ladder that seemingly has no top.

How Ennio Morricone Broke Every Rule of Film Scoring

Before the mid-60s, Western soundtracks were mostly sweeping, orchestral affairs that sounded like Aaron Copland. They were "pretty." They were safe. Ennio Morricone didn't care about safe. He was part of the avant-garde "Gruppo di Improvvisazione Nuova Consonanza" in Rome, which basically means he spent his free time making weird noises with found objects. When his old schoolmate Sergio Leone asked him to score a "Spaghetti Western," Morricone brought that weirdness to the table.

In The Ecstasy of Gold song, he uses a soprano voice—Edda Dell'Orso—not to sing lyrics, but as a pure instrument. There are no words. It’s just "Ahhh." But the way Dell'Orso hits those high notes feels more like a scream of joy mixed with pure greed. It’s haunting. It’s also kinda terrifying if you think about it too much.

The structure is bizarre. Most songs have a verse and a chorus. This doesn't. It’s a "crescendo" in the truest sense of the word. It starts with the piano and the English horn, then adds the strings, then the brass, then the choir, and finally the bells. By the time the trumpets kick in with that triumphant, almost military fanfare, the listener is physically leaned forward. You can't help it. It’s a biological response to the frequency.

The Edda Dell'Orso Factor

Honestly, we don't talk enough about Edda Dell'Orso. She was Morricone's "secret weapon." Without her vocal range, this song is just a decent instrumental. She provides the "Ecstasy" part of the title. Her voice has this crystalline quality that feels like it’s floating above the heavy thrum of the orchestra.

💡 You might also like: Why Love Island Season 7 Episode 23 Still Feels Like a Fever Dream

Morricone once said in an interview that he didn't write "Western music." He wrote music for the soul of the characters. In this scene, Tuco isn't just a bandit. He’s a man possessed. He’s running past thousands of dead soldiers to find wealth, and the music reflects that madness. It’s beautiful, sure, but it’s also frantic. It’s the sound of a man losing his mind to gold.

Why Metallica and the Rest of the World Won’t Let It Go

If you’ve ever stood in a crowd of 50,000 metalheads when the house lights go down and those opening piano notes of The Ecstasy of Gold song start playing over the PA, you get it. James Hetfield has said that it’s the perfect "calm before the storm." It builds this incredible sense of "something big is about to happen."

It’s been used in:

- The Simpsons (multiple times)

- Jackass Number Two

- Commercials for Modelo beer

- Samples by rappers like Jay-Z and Immortal Technique

Why? Because it’s universal. You don't need to know the plot of a 1960s Italian film to feel the emotion. It’s the sound of the "Hustle." It’s the sound of the "Chase."

Interestingly, the recording itself is quite "dry" compared to modern soundtracks. There isn't a ton of reverb. It feels close. It feels like it’s happening in the room with you. When the snare drum hits, it’s sharp. Morricone was known for his "Mousetrap" recording style—capturing sounds in ways that felt immediate and tactile.

The Sad Hill Cemetery Reality

A fun fact that most people miss: the cemetery in the movie wasn't real. The Spanish army actually built it for Sergio Leone. They laid out over 5,000 graves in a massive circle in Burgos, Spain. A few years ago, a group of fans actually went back and dug it up, restoring it to its former glory. If you visit today, you can stand where Tuco stood. If you play the song on your phone while you're there, try not to run. I dare you. It’s impossible.

📖 Related: When Was Kai Cenat Born? What You Didn't Know About His Early Life

The genius of the composition lies in the tempo. It’s about 100 beats per minute, which is slightly faster than a resting human heart rate but slow enough to feel "epic." As it progresses, the layering of instruments makes it feel faster than it actually is. It’s a psychoacoustic trick. Morricone was a wizard at this. He knew exactly when to drop the bass out and when to bring in the chimes to make your skin crawl.

Breaking Down the Instrumentation

Most people think it’s just a "big orchestra." It’s not. It’s actually a very specific, almost "rock and roll" arrangement for the time.

- The Electric Guitar: It’s there, buried in the mix, providing that twangy, surf-rock foundation.

- The Bells: Not church bells, but orchestral tubular bells that sound like a clock ticking toward midnight.

- The Snare: It’s played with a military precision that reminds you there’s a war (the American Civil War) happening in the background of the movie.

- The Piano: It plays the same repetitive motif over and over, acting like a heartbeat.

It’s also important to realize how much Leone and Morricone collaborated. Usually, a composer watches the finished movie and writes music to fit. Not these guys. Morricone often wrote the music before the scene was filmed. Leone would play the music on set through big speakers so the actors could move to the rhythm. When you see Tuco running, he is literally dancing to The Ecstasy of Gold song. His steps match the beat because he was hearing it in real-time.

That’s why the editing is so perfect. The cuts get faster as the music gets louder. It’s one of the few times in history where the music and the film are the same DNA.

Is it the Best Movie Theme Ever?

"Best" is subjective, obviously. John Williams fans will argue for Star Wars or Jaws. But those themes are "leitmotifs"—they represent a person or a thing. The Ecstasy of Gold song represents a feeling. It represents the peak of human desire. It’s much harder to write a song about an abstract concept like "ecstasy" than it is to write a "bad guy theme."

Morricone was nominated for an Oscar many times but didn't win a competitive one until 2016 for The Hateful Eight. It’s a bit of a crime that he didn't win for the "Dollars Trilogy." But then again, icons usually don't need trophies. The fact that his music is still being played in stadiums sixty years later is the real trophy.

👉 See also: Anjelica Huston in The Addams Family: What You Didn't Know About Morticia

The song also bridges the gap between high art and pop culture. It’s played in opera houses by the Danish National Symphony Orchestra (their version on YouTube has over 100 million views, by the way) and it’s played at Coachella. It’s one of those rare pieces of music that makes a 15-year-old kid and a 70-year-old film buff feel exactly the same thing.

Practical Ways to Experience the Music Today

If you really want to appreciate the depth of this track, don't just listen to it on your phone speakers while you're doing dishes. You're missing 60% of the information.

- Listen to the 2004 remastered version from the The Good, the Bad and the Ugly soundtrack. The stereo separation is much cleaner, and you can hear the individual singers in the choir.

- Watch the "Sad Hill Unearthed" documentary. It’s a beautiful look at the legacy of the film and how the music inspired a group of people to literally rebuild a piece of cinema history.

- Find the live version by the Danish National Symphony Orchestra. Watching the soprano hit those notes in person (on video) helps you realize just how difficult the piece is to perform. It requires incredible breath control.

- Try listening to it during a workout. Honestly. If you're on a treadmill and this song comes on, you will run faster. It’s biologically impossible not to.

The Ecstasy of Gold song isn't just a piece of "film music." It’s a monument. It’s a reminder that Ennio Morricone was operating on a level that few others have ever touched. He took a story about three dirty guys looking for a box of money and turned it into a religious experience.

To get the full effect, you need to hear it in the context of the film’s finale. The way it transitions into "The Trio" (the three-way standoff music) is perhaps the greatest ten minutes of audio-visual storytelling ever committed to celluloid. Go back and watch it. Even if you've seen it a dozen times, the hair on your arms will still stand up when that first trumpet blast hits. It’s inevitable.

Next Steps for the Listener

To truly dive into the Morricone soundscape, your next move should be listening to the soundtrack of Once Upon a Time in the West. While "Ecstasy of Gold" is his most famous high-energy track, his work on Once Upon a Time—specifically "Man with a Harmonica"—shows the darker, more atmospheric side of his genius. Comparing the two will give you a full picture of how he redefined the sound of the 20th century.

Check out the "Danish National Symphony Orchestra" performance on YouTube if you want to see the technical complexity of the vocals up close. It puts the sheer difficulty of Edda Dell'Orso’s original performance into a modern perspective. Finally, if you're a fan of physical media, hunt down the 180g vinyl pressing of the soundtrack; the analog warmth brings out the "grit" of the original 1966 Rome recording sessions in a way digital files simply cannot.