If you look at a modern earthquake map of us today, it probably isn’t what you remember from school. Forget just the San Andreas Fault for a second. While California still carries the heavy lifting for seismic anxiety, the literal landscape of risk has shifted toward the center of the country and even the quiet corners of the East Coast. It's weird. You’d think the ground under our feet was a constant, but the data suggests we're living on a much more restless tectonic puzzle than the 1990s maps let on.

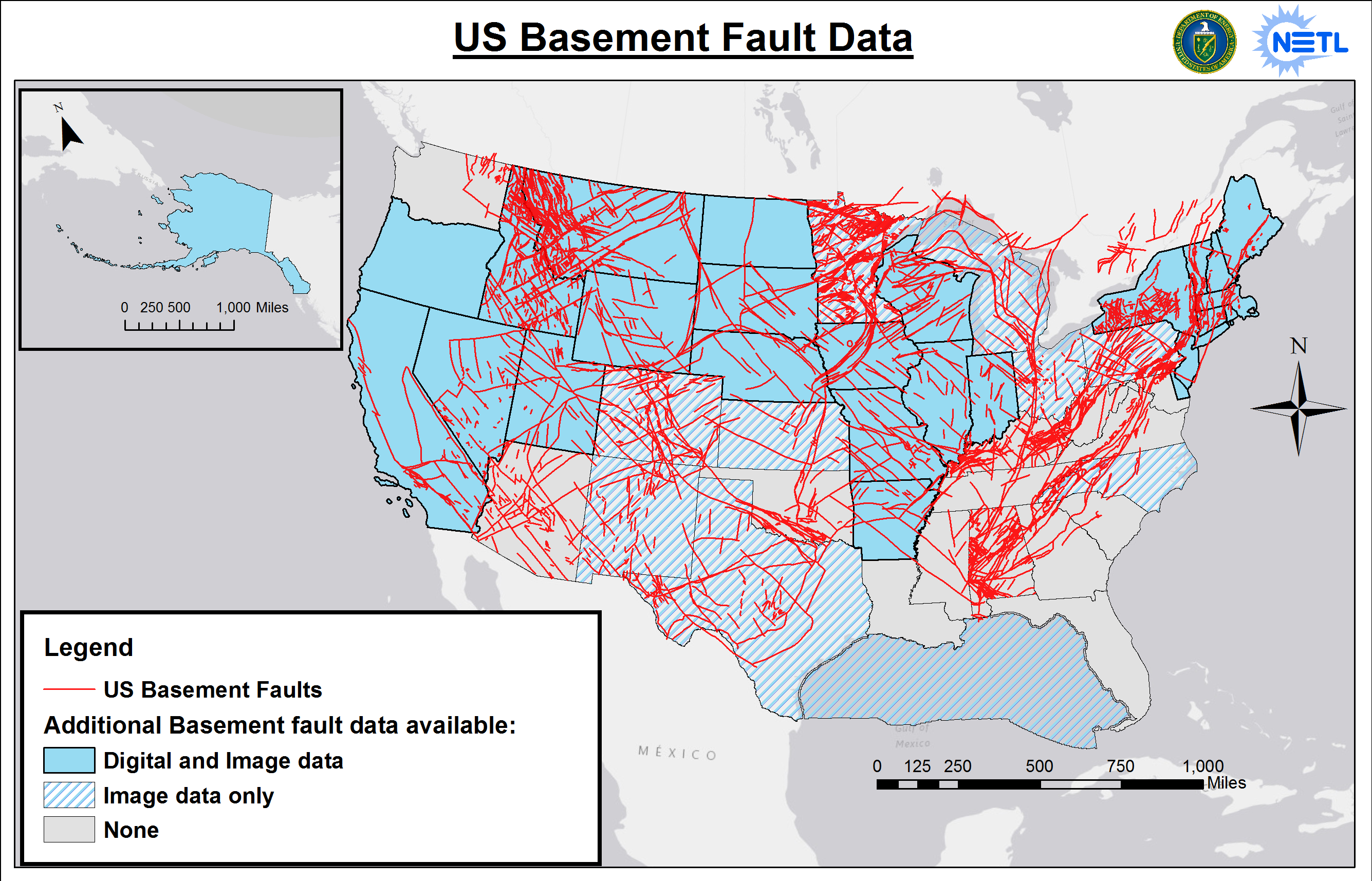

Most people see those big splotches of red on a USGS map and think, "Okay, don't move there." But that's a surface-level take. Honestly, the real story is in the yellow and orange zones where people aren't ready. We’ve seen places like Oklahoma—which used to be seismically "dead"—suddenly light up like a Christmas tree over the last decade. It’s not just natural plates shifting; it’s a mix of ancient deep-crust scars and human activity.

The Red Zones and the "Big One" Obsession

We have to talk about the West Coast. It’s the obvious starting point. When you pull up an earthquake map of us, the Pacific edge is basically a neon warning sign. The San Andreas is the celebrity of faults, but researchers like Dr. Lucy Jones have spent years trying to get us to look at the Haywired scenario or the Cascadia Subduction Zone.

Cascadia is the real monster. It sits off the coast of the Pacific Northwest. If you’re in Seattle or Portland, you aren't just looking at a "shake." You’re looking at a geological reset button. The last time it truly went off was January 26, 1700. We know this because of Japanese "orphan tsunami" records and "ghost forests" in Washington state where the soil just dropped and drowned the trees in salt water. It was a magnitude 9.0. If that happens today, the map doesn't just show a quake; it shows a total infrastructure failure.

California's map is a spiderweb. It isn't just one line. It’s the Newport-Inglewood, the Hayward, the Garlock. Each one has its own personality. Some creep. Some jump. The USGS National Seismic Hazard Model was recently updated in 2023, and it pushed the risk levels higher for a huge chunk of the state. It's not just about the coast anymore; the risk bleeds inland toward the deserts and the mountains more than we used to think.

Why the Middle of the Country is Glowing

Take a look at the New Madrid Seismic Zone. It’s that terrifying little cluster of red right where Missouri, Arkansas, Tennessee, and Kentucky meet. In 1811 and 1812, this area produced quakes so violent they reportedly made the Mississippi River run backward.

📖 Related: Why Fox Has a Problem: The Identity Crisis at the Top of Cable News

People forget this. They shouldn't.

Because the crust in the central US is older, colder, and harder than the "mushy" warm crust in California, seismic waves travel much further. A 6.0 in Memphis would feel like an 8.0 in Los Angeles in terms of the distance the shaking travels. It’s like hitting a piece of glass with a hammer versus hitting a piece of bread. The glass vibrates the whole way across. The earthquake map of us reflects this by showing huge "felt areas" in the East compared to the West.

Then there’s Oklahoma. Around 2015, Oklahoma actually had more earthquakes than California. Yeah, you read 그 right. It wasn't because of "fracking" in the way people usually describe it (the drilling itself), but rather the deep-well injection of wastewater. The state eventually cracked down on regulations, and the numbers dropped, but the map still bears the scars of those induced tremors. It proved that we can literally change the seismic map of a continent with enough industrial pressure.

The East Coast Isn't Safe (Just Rare)

Remember 2011? The Virginia quake? It cracked the Washington Monument. It was a 5.8, which sounds like a "nothing" quake to someone in San Francisco, but it was felt by 50 million people.

The East Coast is full of "blind faults." These are cracks in the earth that don't reach the surface, so we don't know they're there until they move. South Carolina has the Charleston Seismic Zone. In 1886, a massive quake leveled the city. If you look at the current earthquake map of us, Charleston is a lonely island of high risk in the middle of a relatively stable Atlantic plain. It’s a reminder that history repeats itself, even if it takes three hundred years to do it.

👉 See also: The CIA Stars on the Wall: What the Memorial Really Represents

Reading the Map Like a Pro

When you're staring at a USGS (United States Geological Survey) map, you’re usually looking at "Peak Ground Acceleration" or PGA. This isn't just "how big is the quake." It’s "how hard is the ground going to move."

- PGA Percentages: If you see "2% in 50 years," it’s basically a forecast of the worst-case shaking a building might face in a lifetime.

- Soil Type Matters: A map can show you the fault, but it can't always show you the "liquefaction" risk. If you’re on soft landfill in San Francisco or the Back Bay in Boston, the ground can literally turn into a liquid during a quake.

- The 2023 Update: The latest USGS model added massive amounts of data from the last decade. It shows that 75% of the US could experience some level of damaging shaking. That’s a huge jump from previous estimates.

Most people use these maps to check their insurance rates. Honestly, that’s smart. Most homeowners' insurance doesn't cover earthquakes. You have to buy a separate rider. If you live in a "yellow" zone on that map, you might think you're safe, but those are the areas where buildings aren't bolted to their foundations. A moderate shake in a yellow zone can do more damage than a big one in a "red" zone where everything is built to code.

The Problem With "Prediction"

Scientists hate the word prediction. We can’t do it.

We have "forecasts." An earthquake map of us is a probability chart, not a calendar. We know the pressure is building on the Southern San Andreas—it’s been over 300 years since its last major rupture, and its average cycle is about 150-180 years. It’s "overdue," but in geologic time, "overdue" could mean tomorrow or thirty years from now.

We've gotten better at Early Warning Systems, though. Apps like ShakeAlert can give you a 10 to 40-second heads-up. It doesn't sound like much. But it’s enough time for a surgeon to pull a scalpel back, for an elevator to stop at the nearest floor, or for a gas main to shut off automatically. That’s where the map meets real-world tech.

✨ Don't miss: Passive Resistance Explained: Why It Is Way More Than Just Standing Still

Practical Steps Based on Your Location

Don't just look at the map and worry. Do something. If you're in a high-risk zone, or even a moderate one, the steps are basically the same, but the urgency varies.

First, check your foundation. If you have a "crawl space" and your house isn't bolted to the concrete, it can slide off in a 5.0 quake. It’s a relatively cheap fix compared to losing a house. Second, strap your water heater. This is the #1 cause of fires after a quake. The tank tips over, breaks the gas line, and sparks. Boom.

Also, look at your "stuff." Most injuries in US earthquakes aren't from collapsing buildings—our codes are too good for that generally. They're from "non-structural" hazards. Heavy bookshelves, mirrors over beds, and big TVs. Basically, if it’s heavy and tall, it needs a strap.

Lastly, understand the "felt area." If you are in the Midwest or East Coast, your emergency kit needs to be sturdier because help might have to travel further across damaged infrastructure that wasn't built for seismic events.

The earthquake map of us is a living document. It changes as we find new faults and as we pump more stuff into the ground. It’s a guide to the inevitable. You don't have to live in fear of the "Big One," but you definitely shouldn't live in ignorance of the ground you're standing on.

Actionable Takeaways for Residents

- Identify Your Fault: Go to the USGS "Latest Earthquakes" interactive map and zoom into your house. See what's nearby. Don't be surprised if there's a fault line a mile away you never knew existed.

- The "Drop, Cover, Hold On" Drill: It sounds cliché, but it works. Do not run outside. Falling bricks and glass kill people. Stay under a sturdy table.

- Check Your Policy: Call your insurance agent. Ask specifically about "earthquake endorsement." If you're in a high-risk zone in California, look into the California Residential Mitigation Program for grants to retrofit your home.

- The "Seven Days" Rule: The old advice was three days of food and water. Modern FEMA guidance suggests two weeks, but aim for at least seven days. In a major Cascadia or New Madrid event, the roads will be gone. You are your own first responder for the first week.

- Digital Safety: Keep a physical list of emergency contacts. If cell towers are down or your phone is dead, you won't remember your sister's number.

The earth is moving. It’s just doing it slowly—until it isn't. Keeping an eye on the updated earthquake map of us is just part of being a responsible adult in 2026. Know the risk, prep the house, and then go back to living your life.