Imagine you’re a monk in the eighth century. You’re shivering in a drafty stone monastery in Northumbria. Everything is dark, smelling of beeswax and old vellum. Suddenly, you have a vision. But it isn't just any vision of Jesus. It’s a dream where the Cross—the actual physical wood used in the crucifixion—starts talking to you. And it doesn't sound like a victim. It sounds like a warrior.

That is the vibe of The Dream of the Rood.

It is, quite frankly, one of the most jarring and beautiful pieces of literature ever written in Old English. If you’ve ever found medieval poetry dry or boring, this is the one that’ll change your mind. It flips the script on the standard Sunday school narrative. Instead of a passive, suffering figure, we get a "Young Hero" who strips himself naked for battle. Instead of a simple execution device, we get a sentient piece of timber that feels every nail and every insult like a soldier on the front lines.

Honestly, it’s a masterpiece of psychological trauma and religious fervor.

The Vercelli Book and the Ruthwell Cross: Where Did This Come From?

We don't actually know who wrote it. Anonymous is the most prolific author in Old English, after all. Most of what we know comes from the Vercelli Book, a tenth-century manuscript that somehow ended up in Northern Italy. Nobody knows how it got there. Maybe a pilgrim left it behind. Maybe it was a gift. But it sits there in Vercelli, alongside other heavy hitters like Andreas and Elene.

But the poem is older than the book. Much older.

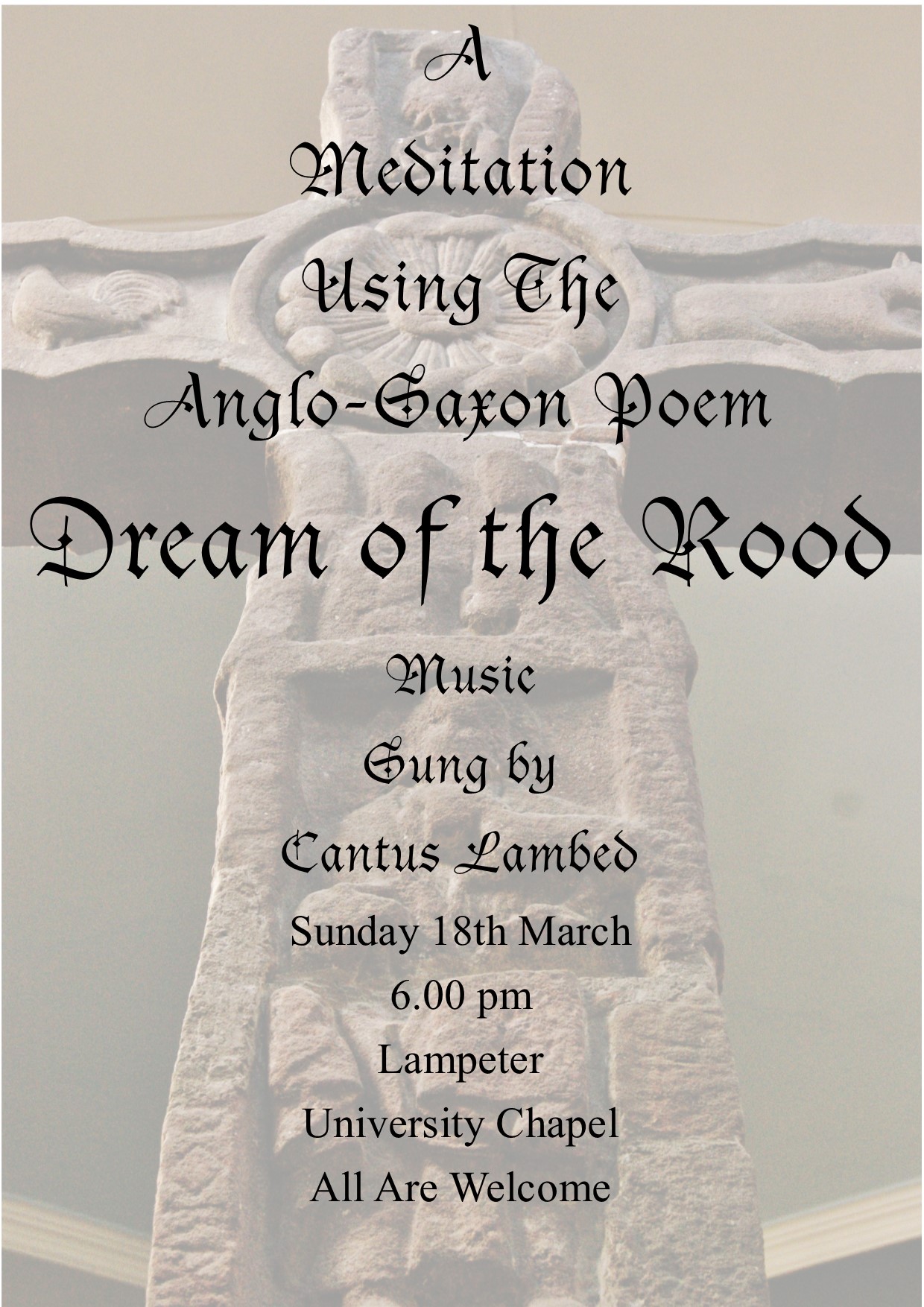

If you travel to Scotland today, specifically to a small church in Ruthwell, you’ll see the Ruthwell Cross. It’s an eighteen-foot-high stone monument. Carved into its edges in runic characters are fragments of The Dream of the Rood. This stone dates back to the early 8th century. That means people were reciting these verses centuries before the Vikings really started wreaking havoc on the English coast.

It’s a bizarre survival story. The poem exists in two forms: one carved in stone runes, the other inked on animal skin. It’s a bridge between the oral traditions of Germanic tribes and the high-literary culture of the Christian Church.

Christ as a Germanic War-Lord

One thing you’ve got to understand about Anglo-Saxon England is that they were obsessed with the "comitatus"—the bond between a lord and his thanes (warriors). If your lord went into battle, you died with him. If you survived and he didn't, you were basically a social pariah.

🔗 Read more: Marie Kondo The Life Changing Magic of Tidying Up: What Most People Get Wrong

The poet who wrote The Dream of the Rood knew exactly what they were doing. They took the story of Christ and translated it into the "warrior code."

In the poem, Jesus isn't dragged to the cross. He "hastened with great zeal" to climb it. He is described as the geong hæleð—the young hero. He is strong and "stout-hearted." He undresses himself, which in a modern context sounds strange, but in the poem, it’s a ritualistic preparation for combat. He is entering the arena.

This was a brilliant marketing move. To convert a bunch of rugged, axe-wielding Saxons, you couldn't just talk about "turning the other cheek." You had to show them a God who was braver than their best generals. You had to show them a God who won by losing.

The Cross as the Tortured Witness

The most fascinating part isn't even Christ, though. It’s the Cross itself. This is where the poem gets really experimental. The narrator—the "Dreamer"—sees the cross flickering between two states. One moment it’s covered in gold and jewels, shining like a trophy. The next, it’s dripping with blood, "sweating" with agony.

Then the wood starts to speak.

The Cross describes its own "arrest." It was cut down at the edge of a forest. It was forced to become a "manning-tree" for criminals. But then, it sees the "Lord of Mankind" rushing toward it. The Cross wants to fall over. It wants to crush the executioners. It has the power to break, but it says, "I dared not bow."

Think about the psychological weight there. The Cross is commanded by God to participate in the killing of God. It becomes a reluctant executioner. It says:

"They pierced me with dark nails. On me, the sores are visible, open wounds of hate... I was all moistened with blood."

💡 You might also like: Why Transparent Plus Size Models Are Changing How We Actually Shop

By the time the poem is halfway through, the Cross and Christ have basically merged into a single entity of suffering. The Cross is a "thane" that has to stand by while its Lord is killed, which is the ultimate nightmare for an Anglo-Saxon warrior. It’s a brilliant use of personification that makes the inanimate feel deeply, painfully alive.

Why the Poem Sounds So Different from the Bible

If you read the Gospels of Matthew or Luke, the tone is very grounded. It’s historical, even if you believe the supernatural elements. The Dream of the Rood is something else entirely. It’s a "dream vision," a genre that would later give us things like Dante’s Divine Comedy.

The language is packed with "kennings"—those metaphorical compound words the Old English poets loved. Instead of saying "sea," they’d say "whale-road." Instead of "body," they’d say "bone-house." In this poem, the Cross is a "victory-tree" (sige-beam).

There’s also a heavy dose of melancholy. Anglo-Saxon poetry is famous for "wyrd" (fate) and a sense that the world is old and breaking down. You see it in The Wanderer and The Seafarer, and you definitely see it here. Even though the poem ends on a hopeful note about Heaven, the primary imagery is one of "dust and ashes" and the lonely dreamer left behind after the vision fades.

It’s lonely. The dreamer wakes up and realizes all his friends are dead or gone, and he’s just waiting for the "Victory-Tree" to come back and take him home. It’s a mood. Honestly, it’s the original "Goth" literature.

Common Misconceptions About the Poem

A lot of people think this is just a straightforward translation of the Bible into verse. It really isn't. Scholars like Barbara Raw and Michael Lapidge have pointed out how much the poem pulls from the Crux Fidelis liturgy and other Latin hymns, but it weaves them into something uniquely English.

Another mistake is thinking it’s purely about the crucifixion. The last third of the poem is actually a sermon. The Cross tells the dreamer to go out and tell everyone what he saw. It becomes an evangelical tool. The dreamer, who started out "stained with sins" and "wounded with foulness," finds a reason to live.

It’s also not just a poem for "medievalists." The influence of this specific type of imagery—the talking object, the warrior-Christ—echoes all the way down to J.R.R. Tolkien. Tolkien was a professor of Anglo-Saxon, and you can see the DNA of The Dream of the Rood in the way he writes about the "Old Forest" or the sacrificial heroism of his characters.

📖 Related: Weather Forecast Calumet MI: What Most People Get Wrong About Keweenaw Winters

How to Actually Read It Today

You shouldn't try to read it in a dry, academic textbook. You need to hear it. Since Old English is a phonetic language, the alliteration—the repetition of initial sounds—is what gives it its power.

In the original, lines don't rhyme. They're held together by a "caesura" (a big pause in the middle) and matching sounds.

Hwæt! Ic swefna cyst secgan wylle...

That "Hwæt" at the beginning? It’s basically "Listen!" or "Yo!" or "Listen up!" It’s a call to attention in a loud mead hall. If you want the best experience, find a recording of someone like Benjamin Bagby performing it. It sounds less like a poem and more like a chant.

What You Can Learn From the Dreamer

There’s a practical takeaway here, even if you aren't religious or into 1,200-year-old manuscripts. The poem is about transformation. It’s about taking something that is a symbol of shame and defeat—a literal gallows—and turning it into a "beacon" of gold and light.

It’s about the perspective shift.

The Cross was just a tree. Then it was a tool of death. Then it was a holy relic. The dreamer was a "solitary" man with no hope. Then he was a man with a mission. It’s a reminder that the stories we tell ourselves about our "scars" or our "burdens" can be rewritten.

Actionable Steps for Exploring Old English Literature

If this sparked something for you, don't just stop at a summary. Here is how you can actually dive deeper into this world without getting a PhD:

- Read the "Crosby" or "Heaney" style translations. Look for a "parallel text" edition. This puts the Old English on the left and Modern English on the right. You’ll start to see words you recognize, like swefn (dream/vision) and beam (tree/beam).

- Check out the Ruthwell Cross digitally. The University of St Andrews has some incredible high-resolution scans and 3D models. You can see the actual runes that inspired the poem. It makes the history feel way less abstract.

- Listen to the sound. Go to YouTube and search for "The Dream of the Rood in Old English." Close your eyes. Don't worry about the meaning yet. Just feel the rhythm of the alliteration. It’s hypnotic.

- Compare it to Beowulf. If you’ve read Beowulf, look at how the "Hero" in that poem compares to the "Hero" in this one. One fights a monster; the other fights death itself. Seeing the overlap in how they talk about glory and fate is fascinating.

- Visit the Vercelli Book online. Many of these ancient manuscripts are now digitized. Seeing the actual handwriting of a scribe from the 900s makes the "Dream" feel much more real than a printed font on a screen.

The poem is a bridge. It bridges the gap between the old gods and the new, between the forest and the cathedral, and between a silent piece of wood and a human soul. It's weird, it's dark, and it's absolutely worth your time.