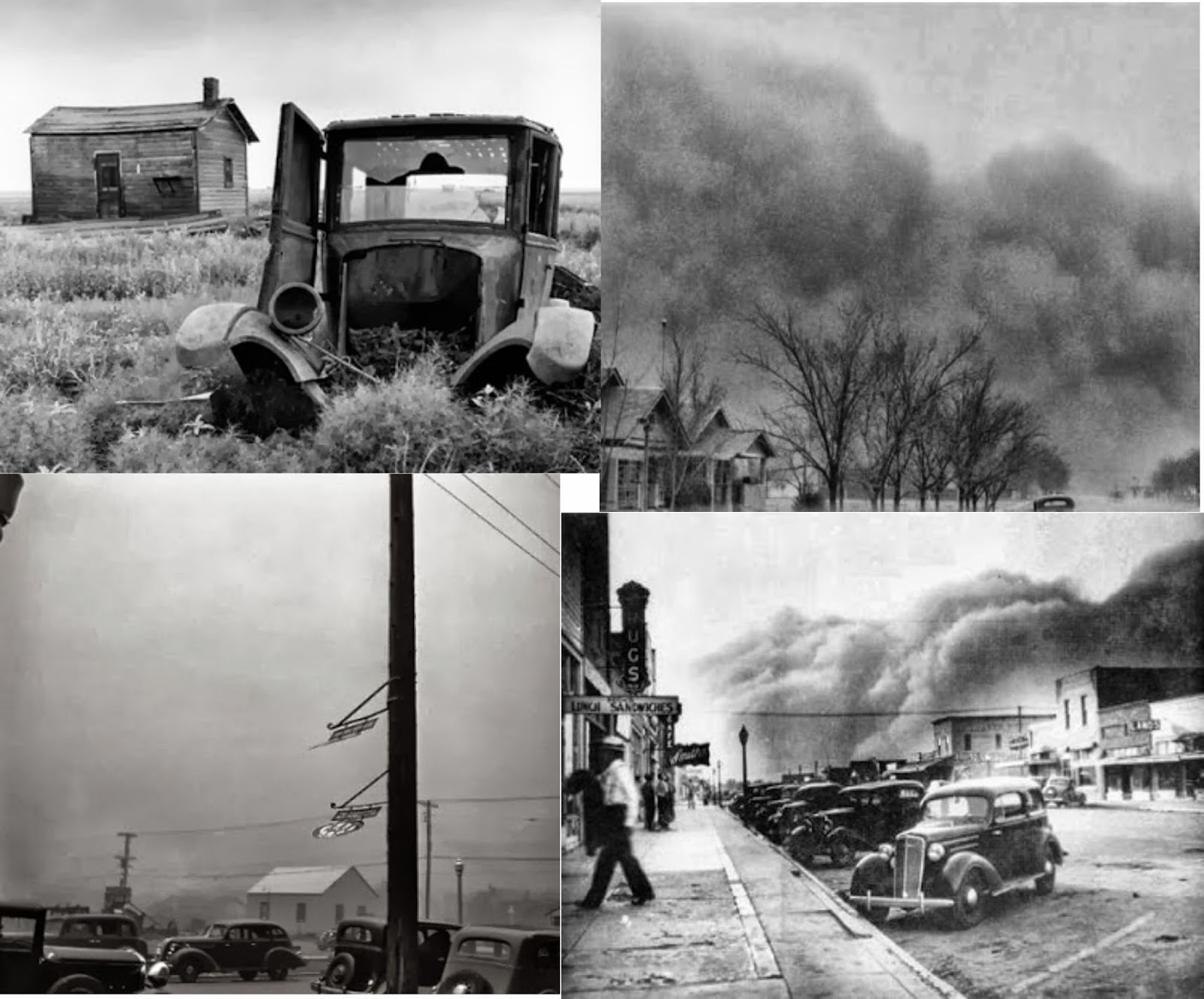

Imagine waking up in the middle of the afternoon to a sky so black you can't see your own hand in front of your face. It isn't a storm or an eclipse. It’s dirt. Just thick, choking, relentless grit that finds its way into your tea, your bedsheets, and eventually, your lungs. This was the reality for families living through the dirty thirties the dust bowl era. It wasn't just a "bad dry spell." It was an environmental apocalypse. Honestly, it's probably the closest the United States has ever come to a total ecological collapse, and we did it to ourselves.

Most people think it was just a lack of rain. While the drought was a massive factor, the actual "dust" part of the Dust Bowl was a man-made disaster. For years, farmers had been ripping up the native buffalo grass of the Great Plains to plant wheat. This grass had deep, tangled root systems that held the moisture and the soil in place for thousands of years. Once that was gone, and the tractors replaced the horses, the soil was basically sitting there like loose flour on a countertop. When the winds picked up in 1931, there was nothing to hold the earth down.

The scale of the destruction is hard to wrap your head around. We're talking about 100 million acres of land across Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Colorado, and New Mexico. It was a slow-motion wreck.

What Really Happened During the Dirty Thirties the Dust Bowl

It started with a boom. During World War I, the price of wheat skyrocketed. The government told farmers to "plant to the fences." They did. They plowed up millions of acres of marginal land that should have stayed as pasture. Then, the Great Depression hit in 1929. Wheat prices cratered. To make up for the loss, farmers plowed even more land, hoping to grow their way out of debt. It was a vicious cycle.

Then the rain stopped.

By 1932, the "black blizzards" began. These weren't your average dust storms. Static electricity became so intense that it would short out car engines or knock people off their feet if they tried to shake hands. People hung wet sheets over their windows to catch the dust. They failed. In the morning, they’d wake up with a layer of silt on their pillows. It was everywhere.

✨ Don't miss: How to Sign Someone Up for Scientology: What Actually Happens and What You Need to Know

Hugh Hammond Bennett, who basically became the father of soil conservation, famously used a dust storm to prove a point to Congress. While testifying in Washington D.C. about the need for land reform, he timed his speech so that a massive dust cloud—traveling all the way from the Great Plains to the East Coast—began to darken the windows of the Capitol. It worked. Congress finally realized that the Midwest was literally blowing into the Atlantic Ocean.

The Human Toll of Dust Pneumonia

It wasn't just about the crops. People were dying. Children especially. They called it "dust pneumonia." Basically, the fine silica in the air would settle in the lungs, causing an inflammatory reaction similar to silicosis found in miners. In some Kansas counties, the death rate from respiratory issues spiked by over 100% during the peak years of the dirty thirties the dust bowl.

You've likely seen the iconic photos by Dorothea Lange, like "Migrant Mother." Those weren't staged. They captured a mass exodus. About 2.5 million people left the Plains states by 1940. It was the largest migration in American history in such a short window of time. But here is something most people get wrong: not everyone went to California. While the "Okie" migration is the most famous, many people just moved to the nearest town or to a neighboring state that wasn't as hit. Those who stayed? They were the "Last Man" clubs—people who swore they wouldn't leave no matter how bad it got.

The Myth of the "Natural" Disaster

We love to blame nature for things because it lets us off the hook. But the dirty thirties the dust bowl was a policy failure. The Homestead Act of 1862 had encouraged people to settle in areas that were climatically unfit for intense row-crop farming. The government gave away 160-acre plots, which was plenty of land in the rainy East, but a death sentence in the semi-arid West. You needed much more land to survive there without exhausting the soil.

- The "Suitcase Farmers" didn't help either.

- These were bankers and lawyers from the cities who bought land, plowed it, sowed seed, and then went back home, leaving the land exposed to the wind.

- When the crops failed, they didn't care. They just walked away.

- The local families were the ones left to breathe the dirt.

Actually, the term "Dust Bowl" was coined by a reporter named Robert Geiger. He used it in an article for the Washington Evening Star after experiencing Black Sunday on April 14, 1935. That day was the worst of them all. A wall of dirt a thousand feet high swept across the plains at sixty miles an hour. Birds fell from the sky. Jackrabbits suffocated in the drifts. It was a day that convinced many that the world was actually ending.

🔗 Read more: Wire brush for cleaning: What most people get wrong about choosing the right bristles

Why This History Matters in 2026

You might think this is just a history lesson, but we are seeing similar patterns today. The Ogallala Aquifer, which is the massive underground water source that currently keeps the Great Plains green, is being pumped dry at an unsustainable rate. Some experts, like those at the Kansas Geological Survey, have warned that parts of the aquifer could be effectively gone within the next few decades.

If the water runs out and a prolonged drought hits again—which it will, because climate cycles are a thing—we could see a "Dust Bowl 2.0." The difference is that today, we have better technology, but we also have more people to feed.

Soil as a Living Organism

One of the biggest takeaways from the dirty thirties the dust bowl was that soil isn't just "dirt." It’s a biological community. After the disaster, the Soil Conservation Service (now the NRCS) started teaching farmers how to contour plow, use cover crops, and plant "shelterbelts." These are long rows of trees designed to break the wind. If you fly over the Midwest today, you can still see these lines of trees. They are a living monument to the lessons learned in the 30s.

But those trees are being torn down. Modern industrial farming equipment is so big that these windbreaks are seen as obstacles. It’s a bit of a "those who forget history are doomed to repeat it" situation. We are removing the very protections that were put in place to prevent another 1935.

Actionable Insights: Lessons from the Grit

If we want to avoid another catastrophe, the solution isn't just "more rain." It's about how we treat the earth under our feet. Honestly, the 1930s taught us that the environment isn't something we can just conquer; it's something we have to negotiate with.

💡 You might also like: Images of Thanksgiving Holiday: What Most People Get Wrong

Prioritize Soil Health

If you manage land, even just a backyard, don't leave bare soil exposed to the elements. Use mulch or cover crops. In a larger context, supporting regenerative agriculture practices—like no-till farming—is the most effective way to keep carbon and moisture in the ground.

Respect Local Ecosystems

The original mistake was trying to make the Great Plains look like Ohio. It's not Ohio. Understanding the "carrying capacity" of land is vital. This means not overgrazing and not planting thirsty crops in desert-adjacent climates.

Water Conservation is Non-Negotiable

The Dust Bowl ended because the rains returned in 1939, and later, because we figured out how to pump water from deep underground. But that underground water isn't infinite. Reducing our reliance on massive irrigation is the only way to ensure the Plains remain habitable for another hundred years.

The dirty thirties the dust bowl proved that the thin layer of topsoil is all that stands between civilization and chaos. It took thousands of years to build that soil and only a decade of bad decisions to blow it away. Protecting it is probably the most important thing we can do for the future of our food supply. No dirt, no food. It’s basically that simple.