George Stevens didn't just want to make a movie. He was a guy who had seen the actual liberation of the camps with his own eyes as a Signal Corps cameraman. That kind of trauma stays with a person. When he sat down to direct the 1959 version of The Diary of Anne Frank, he wasn't looking for a polished Hollywood blockbuster, even though the film ended up being exactly that in terms of scale. He wanted something that felt claustrophobic. Real.

History is messy. Movies usually try to clean it up. But when we talk about the movie Diary of Anne Frank, we’re usually referring to that 1959 black-and-white masterpiece, even though there have been dozens of adaptations since, including the 1980 TV movie and various BBC miniseries. There’s something about that original Cinemascope production that captures the sheer, grinding boredom and terror of hiding in an attic for 761 days.

Millie Perkins was basically a find. She wasn't a seasoned actress, which worked. She had this wide-eyed innocence that made the eventual tragedy feel like a physical weight in the theater. Honestly, if you watch it today, the runtime—nearly three hours—feels daunting. But that’s the point. You’re supposed to feel stuck. You're supposed to feel the walls closing in just like the Frank and Van Daan families did.

The 1959 Movie Diary of Anne Frank and the Battle for Authenticity

People argue about the "Hollywood-ization" of Anne’s story all the time. Critics often point out that the 1959 movie Diary of Anne Frank leans heavily on the Pulitzer Prize-winning play by Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett rather than the raw diary itself. This matters because the play softened some of Anne’s sharper edges. It made her more of a "universal" symbol of hope and less of a frustrated, hormonal, sometimes snarky Jewish teenager living in a crawlspace.

Otto Frank, Anne's father and the only survivor of the Secret Annex, was deeply involved. He was a consultant. Imagine that for a second. Imagine standing on a soundstage in California that looks exactly like the rooms where your wife and daughters were taken to their deaths. He reportedly couldn't even watch the filming. He'd show up, help with details, and then have to leave because the reconstruction was too perfect. It's heavy stuff.

💡 You might also like: Songs by Tyler Childers: What Most People Get Wrong

The film won three Oscars, including one for Shelley Winters, who played Mrs. Van Daan. She actually donated her Oscar statuette to the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam. It's still there. You can go see it. That's a level of commitment you don't see much anymore—an actress realizing the story is infinitely bigger than her own career.

Why the CinemaScope format was a weird but brilliant choice

You’d think a wide-screen format like CinemaScope would be the worst choice for a movie set in a tiny attic. Usually, you use that for Westerns or war epics with sweeping vistas. Stevens did the opposite. He used the wide frame to show how many people were crowded into one shot. You see the elbows, the cramped corners, and the lack of privacy. It makes the Secret Annex feel like a pressure cooker.

- The Sound Design: They used a ticking clock and the sounds of the street below to build tension.

- The Lighting: It’s mostly shadows. Black and white was a conscious choice even though color was available. It kept the "documentary" feel that Stevens was obsessed with.

- The Silence: Some of the most haunting scenes have zero dialogue. Just people breathing and trying not to let a floorboard creak while the Nazis are downstairs.

Comparing the 1959 version to the 2001 miniseries and beyond

If you want the most "accurate" version, some historians point to the 2001 ABC miniseries Anne Frank: The Whole Story. It stars Ben Kingsley as Otto, and it's incredible. It doesn't stop when the Annex is discovered; it follows them to the camps. The 1959 movie Diary of Anne Frank ends with the discovery, focusing more on the spirit of Anne's words: "In spite of everything, I still believe that people are really good at heart."

Some people find that ending too optimistic. It's a bit of a "feel-good" twist on a story that ends in a typhus-ridden mass grave at Bergen-Belsen. But back in the late 50s, audiences were just beginning to process the Holocaust on a mass-media scale. The movie acted as a bridge.

📖 Related: Questions From Black Card Revoked: The Culture Test That Might Just Get You Roasted

There’s also the 2016 German production, Das Tagebuch der Anne Frank. It’s much more modern and treats Anne like a real kid. She’s moody. She’s obsessed with her changing body. She's not just a saint on a pedestal. Comparing these versions shows how our "needs" as an audience have changed. In 1959, we needed a symbol. Today, we want the human.

The controversy of the "Universal" Message

Writer Cynthia Ozick once wrote a famous essay in The New Yorker arguing that the way Anne’s story was adapted for the stage and screen actually "distorted" it. She felt that by making the story about general human hope, the specific Jewish tragedy was erased. It's a valid critique. The 1959 film barely mentions the word "Jew" compared to how often it talks about "the world."

However, you can’t deny the impact. For millions of people, this movie was the first time they ever had to sit with the reality of what happened in occupied Europe. It took a massive, incomprehensible number—six million—and turned it into one girl who liked movie star posters and had a crush on the boy next door.

What to look for when re-watching

- The Stairs: Look at the way the camera angles change when someone goes near the bookcase. It feels like a sheer drop.

- The Food: Pay attention to the plates. The gradual decline of what they’re eating is a subtle bit of storytelling that shows the passing of years.

- The Radio: The BBC broadcasts they listen to are the only link to a world that is moving on without them.

Actionable ways to engage with the history today

If you've watched the movie Diary of Anne Frank and want to go deeper than just the Hollywood version, there are specific steps you can take to get the full picture. The film is a starting point, not the finish line.

👉 See also: The Reality of Sex Movies From Africa: Censorship, Nollywood, and the Digital Underground

First, read the Diary of the Young Girl: The Definitive Edition. This version includes entries that were originally edited out by Otto Frank in the 1940s—entries where Anne is more critical of her mother and more open about her own sexuality. It paints a much more complex picture than the Millie Perkins portrayal.

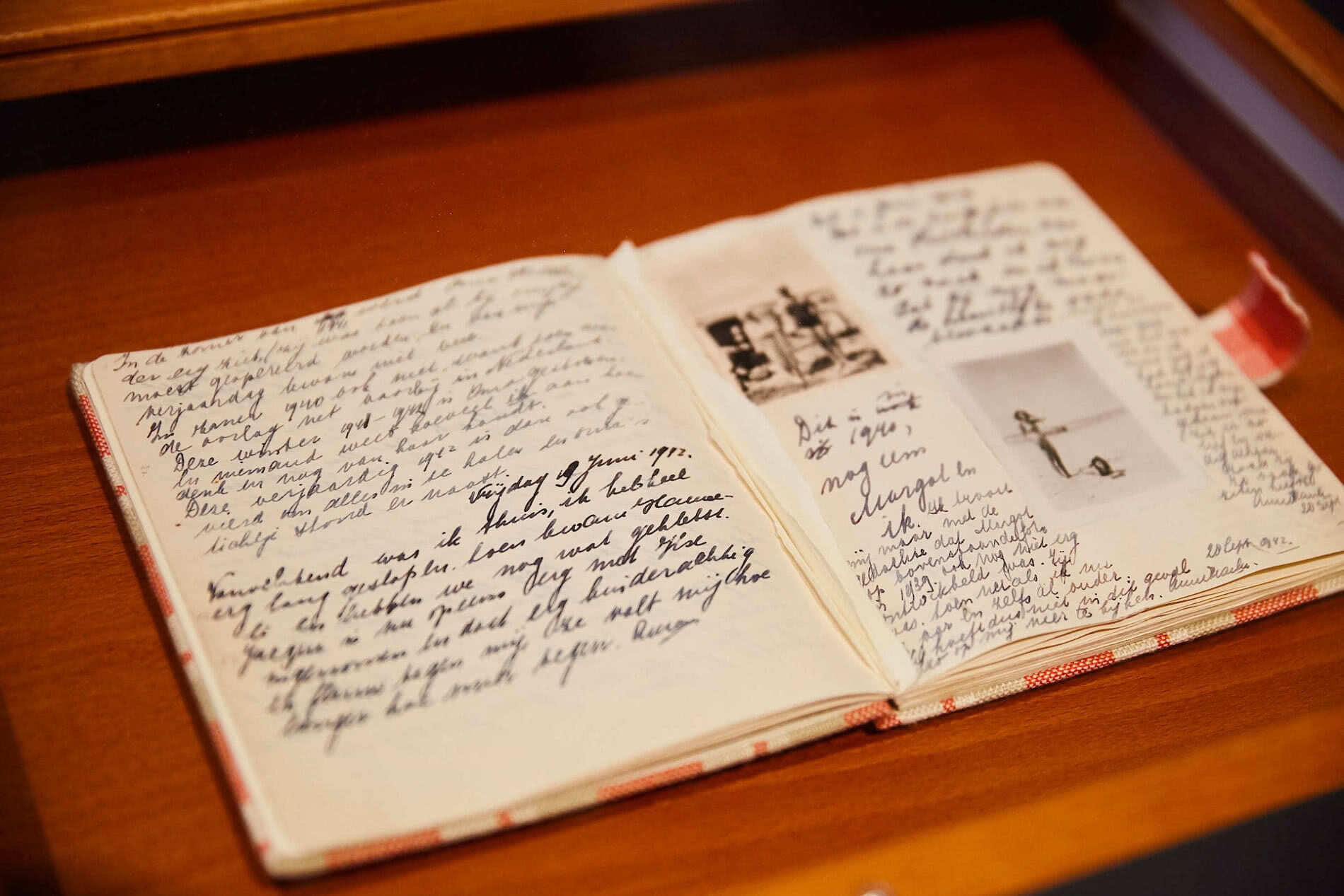

Second, visit the Anne Frank House website. They have a virtual reality tour of the Annex that gives you a spatial understanding that even a movie can’t quite capture. It helps bridge the gap between the "movie set" and the actual historical site.

Third, look into the story of Miep Gies. She was the woman who helped hide them and who eventually saved the diary. There’s a great recent series called A Small Light that focuses entirely on her. It’s the perfect companion piece to the 1959 film because it shows what was happening on the other side of that bookcase.

Watching the 1959 film is a rite of passage for many. It’s not perfect history, but it is perfect filmmaking for its time. It forced a post-war world to look at a face and a name instead of just a statistic. Even if the dialogue feels a bit "Golden Age of Hollywood" at times, the underlying tension is universal. You feel the fear of the siren. You feel the joy of the first snowfall seen through a tiny attic window. That’s why it stays in the cultural consciousness while other biopics fade away.

To truly understand the impact, watch the 1959 film first, then watch the 2001 Kingsley version. You'll see the evolution of how we tell stories about the unthinkable. One focuses on the light of the human spirit; the other refuses to look away from the darkness that tried to blow it out. Both are necessary.