You’ve probably seen it in a dusty chemistry textbook. A jagged line that starts high, climbs a little hill, and then crashes down toward the bottom of the graph. That simple sketch—the diagram of an exothermic reaction—is actually a map of how the universe stays warm. It explains why a campfire keeps you from freezing and why your phone battery gets warm when you're gaming too hard.

Heat moves.

In an exothermic process, the chemicals involved are basically "giving away" their internal energy to the world around them. Think of it like a bank account. If the reactants have $100 and the products only have $20, that extra $80 had to go somewhere. In chemistry, that "somewhere" is usually your hands feeling the heat or a thermometer reading a spike in temperature.

What Actually Happens on the Graph

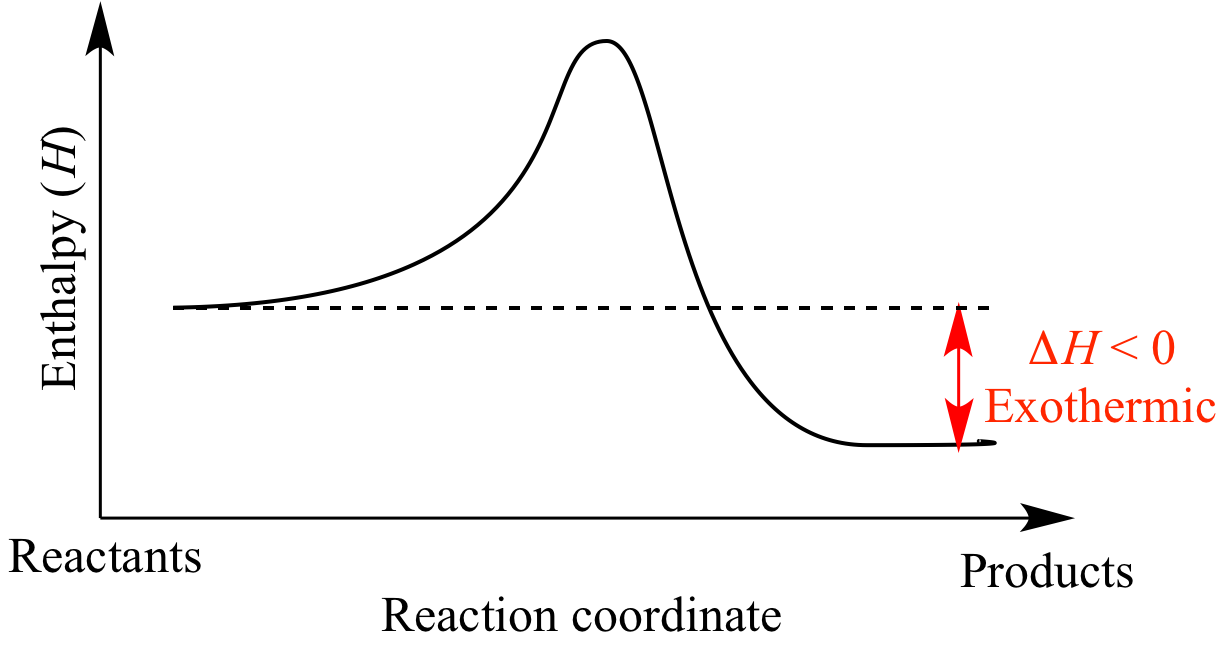

When you look at a diagram of an exothermic reaction, the y-axis represents enthalpy, which is just a fancy science word for the total heat content of the system. The x-axis is the "reaction coordinate." It’s not necessarily time, though we often think of it that way; it's the progress of the transformation from start to finish.

The reactants sit on a high plateau. They have high potential energy because their chemical bonds are relatively weak or unstable. To get the reaction started, you usually need a little "push." This is the activation energy. Even a pile of dry wood won't burn until you strike a match. That match provides the energy needed to break the initial bonds. Once you crest that hill on the diagram, it’s all downhill from there.

The curve drops sharply.

🔗 Read more: Why a 9 digit zip lookup actually saves you money (and headaches)

It ends at a level much lower than where it started. The gap between the starting line (reactants) and the ending line (products) is what chemists call $\Delta H$ (delta H), or the change in enthalpy. In an exothermic reaction, $\Delta H$ is always negative. It’s a loss for the molecules, but a gain for the environment.

The Mystery of the Transition State

At the very peak of that hill on your diagram of an exothermic reaction lies the transition state. It’s a weird, fleeting moment. The old bonds are halfway broken and the new bonds are halfway formed. It’s an "activated complex." It doesn't last. It’s the most unstable point in the entire process. If you don't give the system enough energy to reach this peak, the reactants just bump into each other and bounce away, like a ball that fails to roll over a speed bump.

Real-World Chaos: Combustion and Rust

We talk about these diagrams in sterile classrooms, but they govern the messy reality of life. Take the combustion of methane. When you turn on a gas stove, you're looking at a classic exothermic cliff. Methane ($CH_4$) and oxygen ($O_2$) have high chemical potential energy. Once the spark clears the activation energy hurdle, they collapse into carbon dioxide ($CO_2$) and water ($H_2O$). These products are much more stable. They "prefer" to exist in this low-energy state.

Rusting is different. It’s also exothermic, but it’s a slow burn. If you look at the diagram of an exothermic reaction for iron oxidizing, the slope is the same, but the timeline is stretched. You don't feel the heat from a rusting nail because the energy is being released so slowly that it dissipates into the air instantly. But the math is the same. The energy is still leaving the system.

Why Do We Even Care?

Understanding this energy release is how engineers design everything from hand warmers to rocket engines. A hand warmer is just a controlled exothermic reaction of iron powder oxidizing inside a pouch. If the reaction were endothermic—absorbing heat instead—your hands would freeze.

💡 You might also like: Why the time on Fitbit is wrong and how to actually fix it

In industrial settings, like the Haber process for making ammonia, managing the exothermic nature of the reaction is a life-or-death task. If you don't remove the heat being generated, the temperature spikes, which can actually shift the equilibrium and ruin your yield, or worse, cause a "runaway reaction" where the heat accelerates the process until the equipment explodes.

The Role of Catalysts on the Curve

If you want to change how the diagram of an exothermic reaction looks without changing the start or end points, you use a catalyst. Catalysts are the "tunnel builders" of chemistry.

They don't change the energy of the reactants.

They don't change the energy of the products.

They don't change the total heat released ($\Delta H$).

What they do is lower the activation energy. On the graph, the giant hill becomes a small mound. This means more molecules have enough energy to get over the hump at lower temperatures. Your car's catalytic converter does exactly this, allowing toxic gases to react and turn into less harmful ones at temperatures that won't melt your engine.

Common Misconceptions

People often think "exothermic" means "spontaneous." That’s not quite right. While many exothermic reactions happen easily, the activation energy hill is the gatekeeper. Diamond turning into graphite is technically an exothermic process—graphite is lower energy and more stable. But the activation energy for that "downhill" slide is so massive that your diamond ring isn't going to turn into pencil lead anytime soon.

📖 Related: Why Backgrounds Blue and Black are Taking Over Our Digital Screens

Another mistake is confusing temperature with heat. Heat is the energy moving (the $\Delta H$ on our diagram). Temperature is just the measurement of the average kinetic energy of the particles. A small exothermic reaction might release a lot of heat but only raise the temperature of a massive pool of water by a tiny fraction of a degree.

Analyzing the Bonds

Energy is required to break bonds.

Energy is released when bonds form.

In an exothermic reaction, the energy released when the new, stronger bonds form in the products is greater than the energy it took to break the original bonds in the reactants. It’s a net profit of energy for the surroundings. That’s why the products are "stable." They’ve settled into a deep energy well.

Actionable Takeaways for Mastering Reaction Energy

If you're trying to visualize or calculate these processes, keep these practical steps in mind to avoid common errors:

- Check your signs. Always remember that in an exothermic reaction, $\Delta H$ is negative because the system is losing heat. If you're doing a calorimetry lab and the water temperature goes up, your $\Delta H$ calculation for the chemicals must result in a negative number.

- Sketch the "Hill" first. When drawing a diagram of an exothermic reaction, always draw the reactant line higher than the product line. This visual anchor prevents you from mixing up exothermic and endothermic profiles.

- Identify the Activation Energy ($E_a$). This is measured from the reactant line to the peak. It is never measured from the product line or the bottom of the graph.

- Watch the surroundings. If you are designing an experiment, remember that the "system" is the molecules, and the "surroundings" is everything else (the water, the beaker, the air). In an exothermic reaction, the surroundings get hot because the system got "colder" in terms of its stored chemical potential.

- Calculate bond enthalpies. If you want to predict if a reaction will be exothermic before you even run it, subtract the sum of the bond energies of the products from the sum of the bond energies of the reactants. If the products' bonds are significantly stronger, you're looking at a heat-releasing reaction.

By focusing on the "downhill" nature of the energy profile, you can predict how substances will behave under stress and understand the fundamental drive of the universe to reach a more stable, lower-energy state.