Water moves differently here. If you’ve ever stood on the smashed limestone banks near the Saylorville Dam, you know that the Des Moines River Iowa isn't just a line on a map or a place to dump a kayak. It’s the literal spine of the state. It flows over 500 miles from the glacial plains of southern Minnesota all the way down to the Mississippi at Keokuk, cutting a path through the very soul of the Midwest. But honestly? Most people just drive over it on I-235 and never give it a second thought. That’s a mistake.

The river is complicated. It’s a source of life, a massive recreational playground, and, at times, a genuine threat to the cities built along its edge.

The Massive Scale of the Des Moines River Iowa

You can't talk about this waterway without talking about its sheer reach. It drains nearly 15,000 square miles. That’s a lot of runoff. When you look at the West Fork and the East Fork merging near Humboldt, you’re seeing the birth of a giant. By the time it hits the capital city, it’s a wide, silt-heavy beast that dictates the geography of downtown Des Moines.

The geology is wild. Thousands of years ago, the Des Moines Lobe—the last glacier to poke its head into Iowa—left behind the heavy till and fertile soil that makes this region a global agricultural powerhouse. The river carved through that. It exposed the bedrock. If you head down to Ledges State Park, just a short drive from the main channel, you see these massive sandstone cliffs. They’re stunning. They look like they belong in the Ozarks, not the middle of a cornfield. It's the river's work. It’s old, patient, and relentless.

Dams, Lakes, and the Engineering Fight

We’ve tried to tame it. We really have. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built the Saylorville Lake and Lake Red Rock projects because, frankly, the river used to swallow towns whole. The Great Flood of 1993 is still the benchmark for "bad" in these parts. I remember stories of the water overtopping levees and shutting down the Des Moines Water Works, leaving hundreds of thousands of people without tap water for weeks. It was a wake-up call.

Saylorville is basically a giant bathtub. When the snow melts in the north or those heavy June rains hit, the Corps holds the water back. It protects the city, but it creates this eerie, fluctuating landscape. One week the boat ramps are open; the next, the picnic tables are ten feet underwater. Red Rock, further downstream near Pella, is even bigger. It’s the largest lake in Iowa. But don't let the "lake" name fool you. It’s a reservoir designed to keep the Des Moines River Iowa from destroying everything in its path during a wet spring.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Water Quality

Let’s be real for a second. The Des Moines River has a reputation. If you mention swimming in it to a local, they might give you a look. There’s a long-standing tension between the agricultural industry and urban water needs. Nitrate levels are a constant topic of conversation in the Iowa Legislature. The Des Moines Water Works actually sued three upstream counties back in 2015 over drainage tile runoff. They lost the lawsuit on a legal technicality, but the point was made: the river is carrying a heavy load of fertilizer and sediment.

📖 Related: Bryce Canyon National Park: What People Actually Get Wrong About the Hoodoos

Does that mean it’s "dead"? Not even close.

It's actually a thriving ecosystem if you know where to look. You’ve got walleye, smallmouth bass, and some of the biggest channel catfish you'll ever see. The Iowa Department of Natural Resources (DNR) monitors this stuff constantly. While there are consumption advisories for certain fish due to mercury or PCBs—standard for most large midwestern rivers—the water is vastly cleaner than it was in the 1970s. We’re seeing the return of bald eagles in massive numbers. You can see dozens of them nesting in the tall cottonwoods along the banks near Ottumwa. It’s a slow recovery, but it’s happening.

The Recreational Pivot

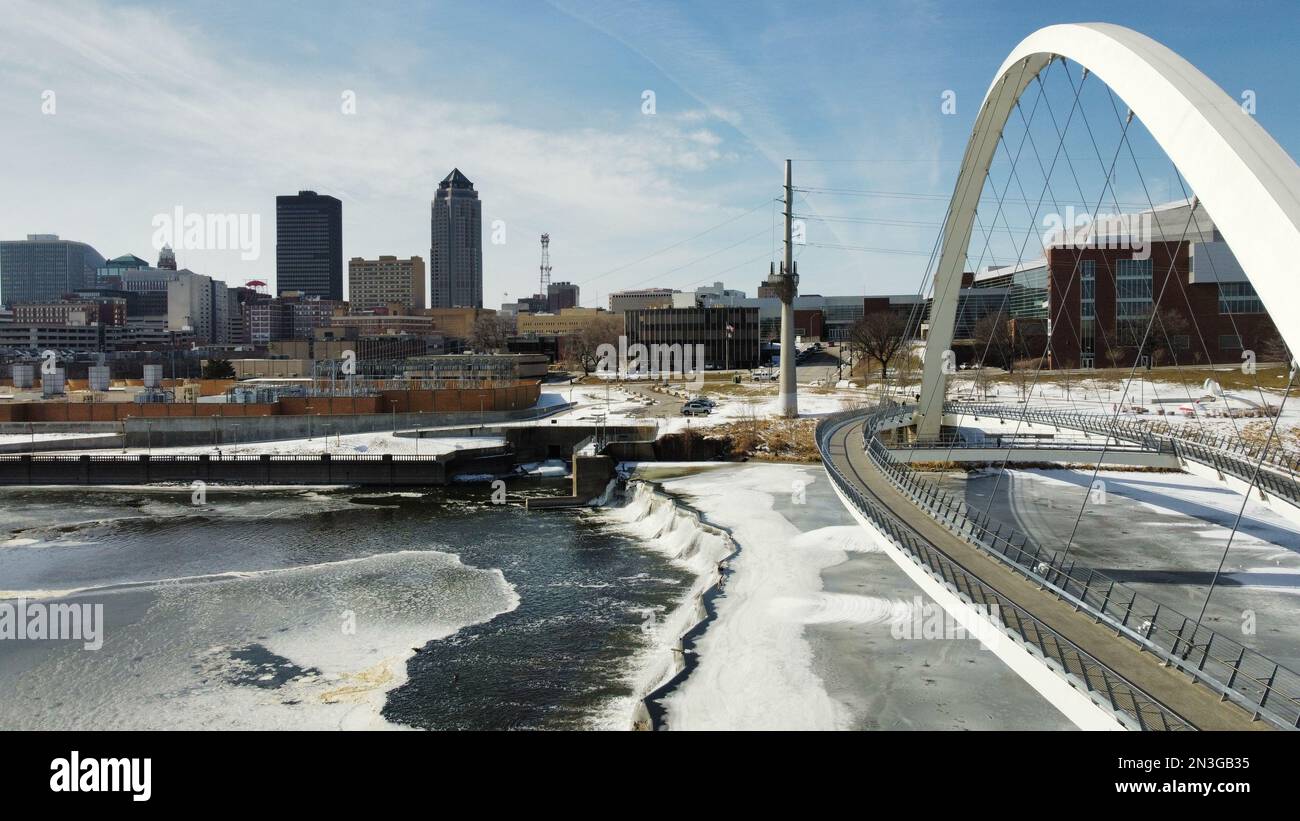

Something cool is happening in the metro area. For decades, the city turned its back on the river. It was the "back alley" of the town. Now? It’s the front porch. The Lauridsen Skatepark—the largest in the country—sits right on the bank. The Principal Riverwalk connects the east and west sides with that iconic arched bridge that glows at night.

But the real game-changer is the ICON Water Trails project.

This is a massive, multi-million dollar initiative to turn the Des Moines River Iowa into a world-class destination for paddling and whitewater. They’re actually mitigating the "deadly low-head dams" (often called drowning machines) and replacing them with drops and rapids that kayakers can actually use. It’s shifting the river from something you look at to something you actually get into.

The Lost History of the Des Moines

Before the settlers showed up with their grids and plows, this was a highway for the Ioway and Sauk tribes. The name itself is a bit of a linguistic accident. French explorers called it La Rivière des Moingona, referring to the Moingona tribe. Eventually, "Moingona" got shortened and morphed into "Moines," which means "monks" in French. People started thinking it was the "River of the Monks," but there were never any monks. It was just a misunderstanding of an Indigenous name.

👉 See also: Getting to Burning Man: What You Actually Need to Know About the Journey

Steamboats used to chug up this river. Can you imagine? In the mid-1800s, boats like the Agatha actually made it all the way up to Fort Des Moines. They carried flour, pork, and people. But the river is fickle. It’s sandy and prone to shifting bars. Once the railroads arrived, the steamboat era died almost overnight. The river went from being a trade route to a power source for mills, and eventually, a source of cooling water for power plants.

Navigating the Lower River

Downstream of Des Moines, the vibe changes. It gets wilder. As the river winds through Marion, Mahaska, and Wapello counties, the valley deepens. This is "Coal Country." If you look closely at the bluffs near Eldon, you can still find remnants of the old coal mines that fueled Iowa’s early industrial growth. The river here is wide and muscular.

Ottumwa is a quintessential river town. It’s defined by the water. The way the city is cradled in a bend of the Des Moines River Iowa shows just how much the topography dictated where we built. This lower stretch is a favorite for long-distance paddlers. You can put a canoe in at Red Rock and disappear for days, camping on sandbars and seeing nothing but deer, herons, and the occasional farmhouse.

Living With the River: Practical Insights

If you’re planning on visiting or exploring the river, you have to respect the flow. This isn't a theme park. The current is deceptively strong, especially near the bridge pilings and the remaining low-head dams.

Safety and Navigation Basics:

- Check the USGS Gauges: Before you go, look up the real-time flow data. If the river is running high (often measured in cubic feet per second), stay out. It’s full of "strainers"—fallen trees that can trap a boat.

- The Dam Danger: Never, ever approach a low-head dam from upstream or downstream. The recirculating current at the base can trap even a strong swimmer.

- Public Access: Use the Iowa DNR’s interactive map. It shows every legal boat ramp and portage point.

- The Silt Factor: Wear old shoes. The "Iowa Mud" is real. It’s a fine, sticky silt that will claim your flip-flops if you aren't careful.

The Des Moines River is also a major flyway. If you’re a bird watcher, the spring migration is insane. Pelicans—yes, actual white pelicans—stop over by the thousands on their way north. They look like white islands floating on the water. It’s one of those things you don't expect to see in a landlocked state.

✨ Don't miss: Tiempo en East Hampton NY: What the Forecast Won't Tell You About Your Trip

The Future of the Water

We’re at a crossroads. The next twenty years will decide if the Des Moines River Iowa becomes a clean, vibrant recreational hub or if it remains a utility corridor struggling with runoff. There’s a lot of money being poured into "oxbow restoration." By reconnecting the river to its old, winding loops that were cut off for farming or flood control, we’re creating natural filters for the water.

It’s about balance. We need the river for corn. We need the river for drinking water. We need the river for the $6.6 billion outdoor recreation economy in Iowa. Sometimes those needs clash.

Actionable Steps for Explorers

If you want to actually experience the river rather than just reading about it, here is how you do it right:

- Start at the High Trestle Trail: While not the river itself, the bridge crosses the Des Moines River valley near Madrid. It’s 13 stories high. Looking down at the water from that height gives you a sense of the scale of the valley the river carved.

- Paddle the "Middle Des Moines" Water Trail: The stretch from Algona to Humboldt is underrated. It’s intimate and scenic.

- Visit the Center Street Bridge in DSM: Go at sunset. You’ll see the city lights reflecting off the water. It’s the best view of how the urban environment interacts with the natural flow.

- Volunteer for River Cleanup: Organizations like River Action or local watershed groups do annual hauls. You’d be surprised what comes out of the mud—tires, old signs, and occasionally, historical artifacts.

The Des Moines River isn't going anywhere. It’s been here since the ice melted, and it’ll be here long after we’re gone. The more we pay attention to it, the better off the state is. It’s a living history book. You just have to be willing to get a little mud on your boots to read it.

To get the most out of your time on the water, download the Iowa DNR's "Where to Fish" app and check the weekly fishing report specifically for the Des Moines River reach you plan to visit. If you are paddling, always file a float plan with a friend, as cell service can be spotty in the deep valleys of the lower river. For those interested in the engineering side, the Saylorville Lake Visitor Center offers a deep look into how the 1993 and 2008 floods changed the way we manage the water today.