You're standing in line for a coffee. Or maybe you're staring at the price of eggs, wondering when exactly a dozen became a luxury item. It’s annoying. But behind that price tag—and every other price tag in existence—is a simple, crossed-line visual known as the demand and supply graph. Economists love it. Most people ignore it. Honestly, though, if you want to understand why your rent just spiked or why graphics cards are finally affordable again, you have to look at those two intersecting lines.

Markets are messy. People are unpredictable. Yet, this graph manages to pin down the chaos of human desire and resource scarcity into a single point. It’s the "X" that marks the spot where a deal actually happens.

The Downward Slope of Human Greed

Let’s talk about the demand curve first. It’s the line that starts high on the left and slides down to the right. There’s a reason for that. It’s called the Law of Demand. Basically, it’s just a fancy way of saying humans are cheap. When something is expensive, we buy less of it. When it’s cheap, we load up.

Think about $5 gallons of gasoline. You probably stop taking those unnecessary Sunday drives. You might even carpool. But if gas drops to $1.50? You’re suddenly planning a cross-country road trip. The demand curve captures this psychological tug-of-war.

Economists like Alfred Marshall, who popularized these ideas in his 1890 book Principles of Economics, realized that "utility" or satisfaction drops as we consume more of the same thing. That first slice of pizza is amazing. The fifth slice? Kinda makes you feel sick. Because that fifth slice is less valuable to you, you’re only willing to buy it if the price is much lower. That’s why the line slopes down.

Why Producers Are the Opposite

Now, look at the supply curve. It’s the contrarian. It starts low on the left and climbs up to the right. This represents the perspective of the business owner. If you’re selling lemonade and it costs $10 a cup, you’re going to be out there every single day with five different stands. You’ll hire your neighbors. You’ll buy the high-end lemons. High prices mean high profits, so you want to provide as much as possible.

But if lemonade drops to $0.10 a cup? You’re probably going to close up shop and go play video games instead. It’s not worth the effort.

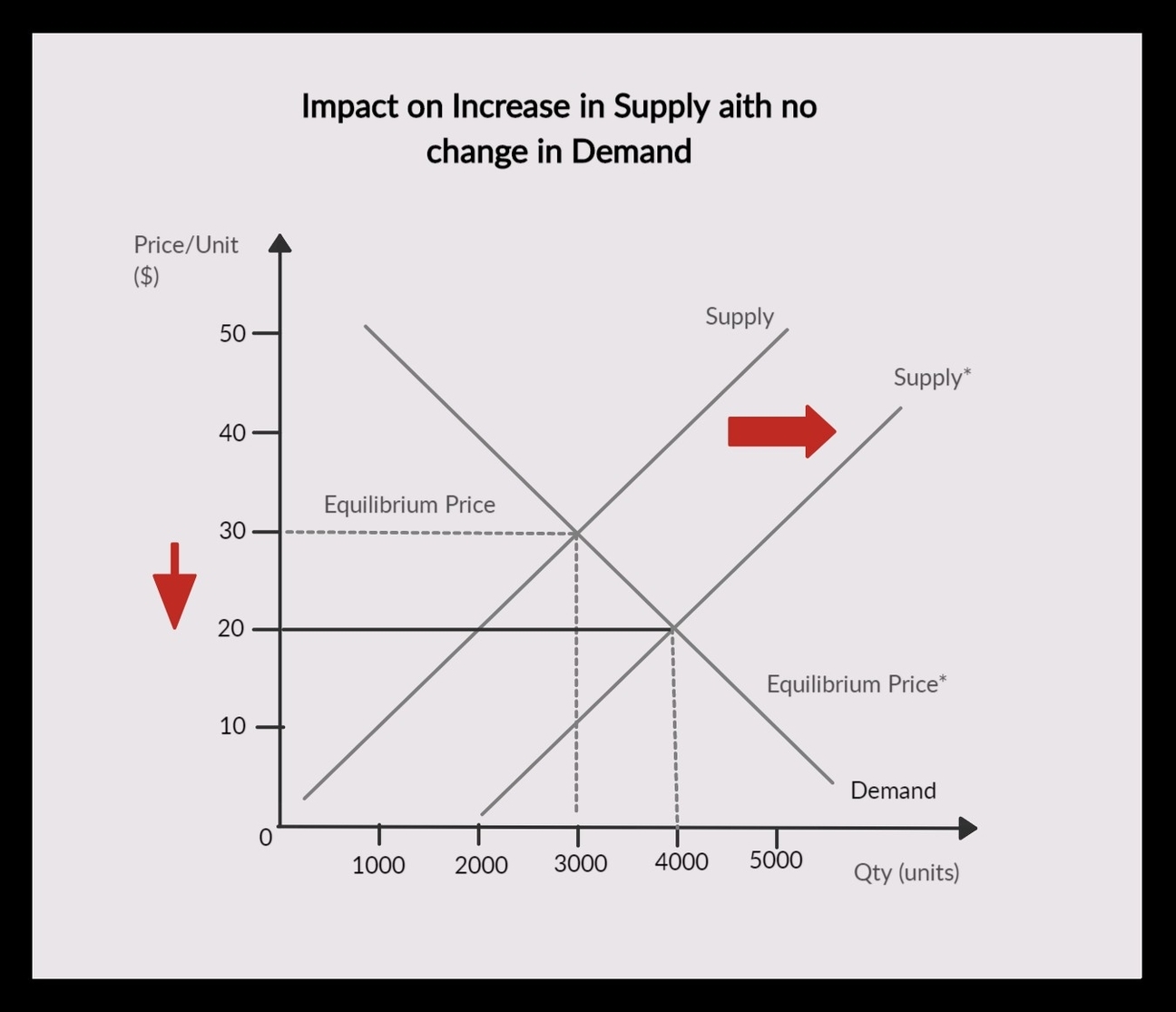

This creates a natural tension. Buyers want low prices; sellers want high prices. They are fundamentally at odds. In a functional market, they meet in the middle at a point called equilibrium. This is the "sweet spot" where the amount of stuff sellers want to sell exactly matches the amount of stuff buyers want to buy. No leftovers, no lines out the door.

When the Lines Start Dancing

The demand and supply graph isn't a static photo. It’s more like a living, breathing thing. It shifts.

✨ Don't miss: So, What Is a Freighter Exactly? The Unsung Giants of Global Trade Explained

Take the 2020-2022 semiconductor shortage. It was a mess. First, demand for laptops and webcams skyrocketed because everyone was suddenly working from their kitchen tables. On the graph, the demand curve shifted to the right. When demand shifts right—and supply stays the same—the price has nowhere to go but up.

Then, factories in Taiwan and South Korea faced lockdowns. Supply shifted to the left.

When you have a rightward shift in demand (more people wanting stuff) and a leftward shift in supply (less stuff available), you get a price explosion. That’s why a PlayStation 5 was basically worth its weight in gold for two years.

The Myth of "Fixed" Prices

A lot of people think prices are set by some greedy CEO in a boardroom. While companies definitely try to influence things, they aren't all-powerful. If a company sets a price above the equilibrium point, they end up with a surplus.

Imagine a sneaker brand releases a shoe for $500, but the market thinks it’s only worth $200. The shoes sit on the shelves. Dust gathers. Eventually, the store has a "clearance sale." That sale is just the market forcing the price back down toward the equilibrium point on the demand and supply graph.

On the flip side, if the price is too low, you get a shortage. This happened with rental housing in cities like New York and San Francisco. When rent control laws keep prices below the equilibrium, more people want apartments than there are apartments available. The result? 100 people showing up for one open house and "under-the-table" payments to landlords. The graph doesn't care about "fairness"; it only cares about where the lines cross.

Elasticity: The Rubber Band Effect

Not all lines are created equal. Some are steep, and some are flat. This is what experts call elasticity.

If the price of insulin doubles, people who need it still buy it. They don't have a choice. Their demand is "inelastic." On the graph, that line is almost vertical. But if the price of a specific brand of sparkling water doubles? People just buy a different brand or drink tap water. That demand is "elastic"—the line is very flat.

Understanding this is crucial for businesses and governments. If a government puts a heavy tax on an inelastic product (like cigarettes), people keep buying them, and the government makes a lot of tax revenue. If they tax something elastic (like luxury jewelry), people just stop buying it, and the tax revenue disappears.

Real-World Nuance and the "Invisible Hand"

Adam Smith famously called this the "Invisible Hand." It’s the idea that by pursuing their own interests—buyers seeking deals and sellers seeking profits—society magically ends up with the right amount of goods at a mostly sustainable price.

💡 You might also like: Converting 500 Pesos to USD: Why the Rate You See Isn't Always the Rate You Get

But it’s not perfect. The demand and supply graph assumes "perfect competition." It assumes everyone has all the information and there are no "externalities."

Externalities are the "oops" moments of economics. If a factory produces cheap steel (supply) because it dumps chemicals in a river for free, the graph looks great. The price is low! But the community is paying a "hidden" cost in health and clean-up. This is why economists like Arthur Pigou argued for taxes on things like pollution—to shift the supply curve to a place that reflects the actual cost of production.

Actionable Steps for Navigating Markets

Stop looking at prices as fixed obstacles. They are signals. If you can read the signals on the graph, you can make better financial decisions.

- Wait for the Surplus: If you see a product with high inventory and low foot traffic, the market is in a surplus. A price drop is inevitable. Don't buy the "new" tech or fashion at launch if the supply curve is clearly about to shift right as manufacturing ramps up.

- Identify Inelasticity in Your Own Budget: Look at what you buy that you "can't live without." These are your vulnerabilities. If the price of these items spikes, you have no leverage. Diversifying your needs—finding substitutes—flattens your personal demand curve and gives you more power.

- Watch the Input Costs: If the price of raw materials (like lithium for batteries) starts climbing, you know the supply curve for EVs will eventually shift left. If you’re planning a big purchase, buying before those input costs hit the retail level can save you thousands.

- Check the Competition: A market with only one supplier (a monopoly) doesn't follow the standard supply curve. They can restrict supply to keep prices artificially high. If you're buying in a market with no competition, expect to pay a "monopoly tax."

The demand and supply graph is more than just a classroom exercise. It’s a map of human behavior. Every time you buy something, you’re adding a tiny data point to that graph. You’re part of the lines. Understanding how they move won't just make you smarter in a business meeting; it'll keep more money in your pocket when the rest of the world is wondering why things got so expensive.