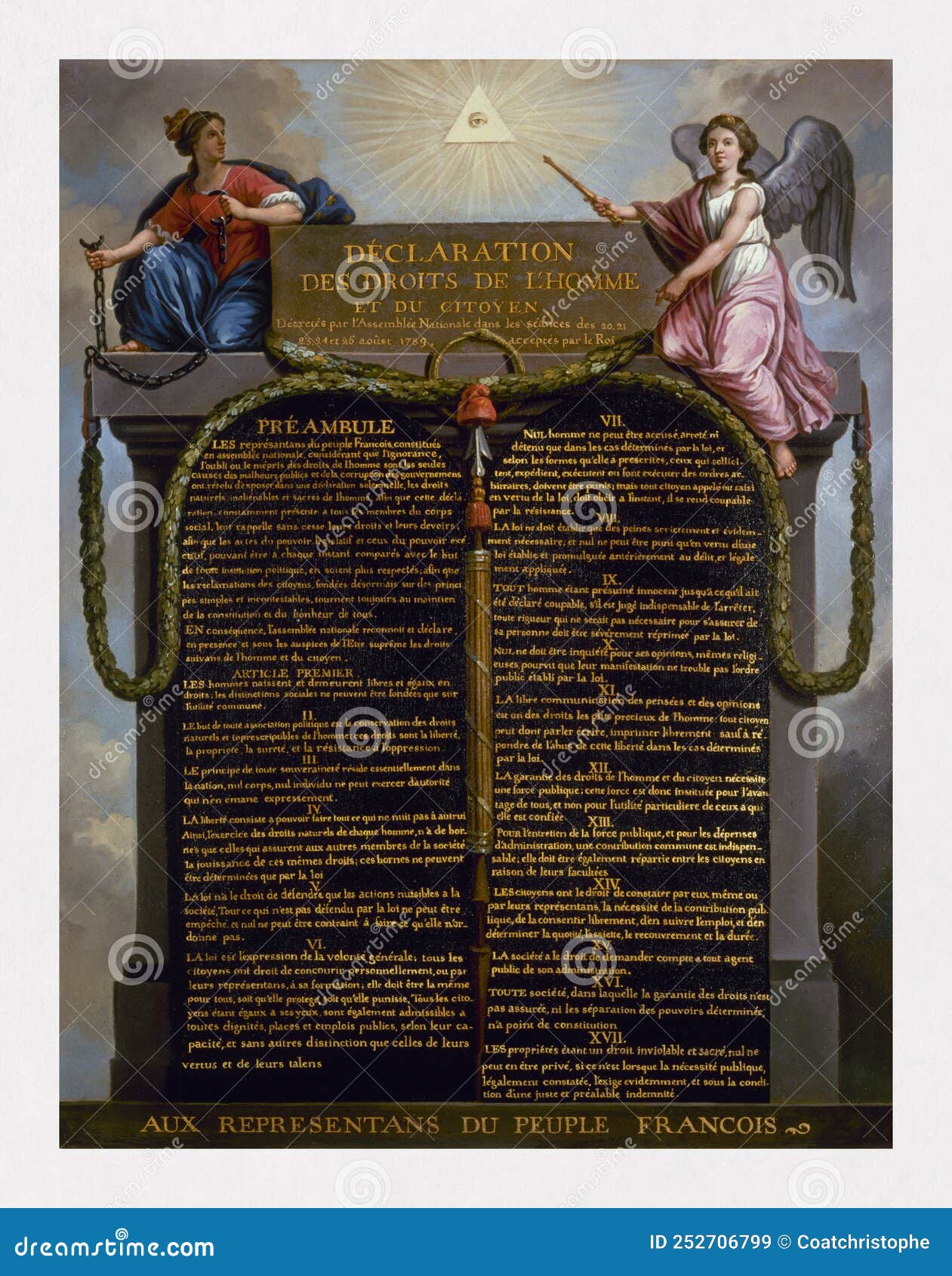

History is messy. People like to think the French Revolution was just a bunch of angry peasants storming a prison, but the real heart of the thing was a piece of paper. Specifically, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen. It’s basically the DNA of modern democracy. If you live in a country where you can complain about the government without getting thrown in a dungeon, you owe a massive debt to a group of sleep-deprived Frenchmen in August 1789.

They weren't just writing a law. They were killing an old world.

Before this, you weren't a citizen. You were a subject. That difference is huge. A subject exists to serve the King; a citizen has rights that even a King can't touch. Honestly, it’s wild how much we take this for granted now. Back then, suggesting that "men are born and remain free and equal in rights" was essentially an act of war against every throne in Europe.

What the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen actually said

The Marquis de Lafayette was the guy who drafted the initial version. Yeah, the same Lafayette who helped out in the American Revolution. He was buddies with Thomas Jefferson, and you can totally see the family resemblance between the French document and the Declaration of Independence. But the French version went further. It wasn't just about breaking away from a ruler; it was about defining what it means to be a human being in a political society.

There are 17 articles. They don't cover everything—and we’ll get into the messy parts later—but the core ideas are heavy hitters.

Article 1 is the big one: "Men are born and remain free and equal in rights."

It sounds simple. It’s not. In 1789, your "rights" depended on who your father was. If you were a noble, you had the right to own land and pay zero taxes. If you were a peasant, you had the right to work yourself to death and pay for the noble's wine. The Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen nuked that entire system in a few sentences.

Then you have Article 2. It says the whole point of any political association is to preserve natural rights: liberty, property, security, and resistance to oppression. Notice that "resistance to oppression" part? It basically gave the public a legal permit to revolt if the government started acting like a tyrant.

👉 See also: Otay Ranch Fire Update: What Really Happened with the Border 2 Fire

The Law as an expression of the "General Will"

Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s fingerprints are all over this thing. He had this idea of the "General Will." The Declaration picked it up and ran with it. Article 6 says that law is the expression of the general will and every citizen has a right to participate in its formation.

This was a total pivot.

Power didn't come from God anymore. It didn't come from the "Divine Right of Kings." It came from the people. If you’ve ever voted, or even just yelled about a politician on the internet, you’re exercising a right that was solidified right here. It’s also where we get the idea that you’re innocent until proven guilty (Article 9). Before this, if the King didn't like you, you were guilty until you could prove otherwise—which was usually impossible from the bottom of a hole in the ground.

The things nobody talks about: Who was left out?

Here is where it gets complicated. The Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen has a pretty glaring flaw right in the title. "Man."

In 1789, "Man" didn't mean "Humans."

It meant men. Specifically, property-owning men.

Olympe de Gouges, a brilliant playwright and activist, saw this immediately. She realized that the "universal" rights weren't so universal. In 1791, she wrote the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen. She argued that if women had the right to go to the guillotine (which she eventually did), they should have the right to go to the speaker's podium. The revolutionaries weren't ready for that. They talked a big game about liberty, but they weren't about to give women the vote.

✨ Don't miss: The Faces Leopard Eating Meme: Why People Still Love Watching Regret in Real Time

Then there’s the issue of slavery.

The Declaration was being read in French colonies like Saint-Domingue (now Haiti). Imagine being an enslaved person and hearing that "men are born and remain free and equal." It sparked the Haitian Revolution, the only successful slave revolt in history that led to the founding of a state. But back in Paris? The National Assembly dragged its feet. They loved liberty in the streets of Paris, but they loved the sugar profits from the Caribbean even more. It took years and a lot of bloodshed for those "universal" rights to actually apply to people of color in the colonies.

Why it’s not just a dusty old document

You might think this is just a history lesson, but the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen is actually a living document. It’s literally part of the current French Constitution. Since 1958, the French "Bloc de constitutionnalité" includes this 1789 text. That means judges still use it to strike down laws that violate basic freedoms.

It’s also the grandfather of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) adopted by the United Nations in 1948.

Think about the "Cancel Culture" debates or arguments over "Free Speech." Those are just modern versions of the tensions found in Article 11, which says "the free communication of ideas and opinions is one of the most precious of the rights of man." But it adds a catch: you are responsible for the "abuse of this liberty."

The French were already worried about the line between "free speech" and "harmful speech" over 230 years ago.

The shift from Subject to Citizen

The most radical thing this document did was change our psychology.

🔗 Read more: Whos Winning The Election Rn Polls: The January 2026 Reality Check

We don't think like subjects anymore. If a police officer pulls you over, you know you have rights. If a boss tries to stop you from practicing your religion, you know there’s a legal framework to protect you. That "knowing" started here. It created the "Citizen."

A citizen is an active participant. A subject is a passive recipient.

Common misconceptions about the Declaration

People often mix this up with the US Bill of Rights. They are similar, sure, but the French version is more philosophical. The US Bill of Rights is a list of things the government can't do to you. The French Declaration is a statement of what a human being is.

Another myth? That it stopped the violence.

Hardly.

The ink was barely dry on the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen before the Reign of Terror started. Maximilien Robespierre, one of the guys who championed these rights, eventually oversaw a system that executed thousands of people without the very fair trials the Declaration promised. It’s a grim reminder that a piece of paper is only as good as the people enforcing it. Rights aren't magic spells; they’re social contracts that require constant maintenance.

Actionable Insights: How to use this history today

Understanding the Declaration isn't just for trivia night. It gives you a framework for evaluating the world around you.

- Audit your own rights: Whenever a new law is passed, ask: does this treat me as a "subject" or a "citizen"? If it removes your agency or your right to participate in the "General Will," it’s a step backward.

- Recognize the gaps: Just as the 1789 document ignored women and enslaved people, modern systems often have blind spots. Look at who is currently "invisible" in our legal protections.

- Read the source: Don't take a textbook's word for it. The Declaration is short—only 17 articles. Reading it takes five minutes, and it’s one of the few historical documents that actually lives up to the hype.

- Support institutional checks: The Declaration failed when the courts failed. Supporting a fair, independent judiciary is the only way to keep "Natural Rights" from becoming "Suggestions."

The French Revolution was a bloody, chaotic, often hypocritical mess. But in the middle of that fire, they managed to forge a set of ideas that eventually changed the world. The Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen basically gave us the modern world’s operating system. It’s buggy, it crashes sometimes, and it definitely needs updates—but it’s better than the one that came before it.

To truly understand the modern political landscape, start by looking at the tension between individual liberty and the "General Will." That’s where the real action is. Study the evolution of Article 11 regarding free speech in the digital age, as this remains the most contested territory in modern democracy.