Leo Tolstoy was having a midlife crisis, but not the kind where you buy a flashy horse and carriage or start wearing silk robes. It was the kind where you look at a wall and realize that everything you’ve built—the fame, the family, the money—is a hollow shell. Around 1886, he dropped The Death of Ivan Ilyich, a novella so sharp it still makes modern readers feel like they’re the ones lying on that agonizing sofa in 19th-century St. Petersburg.

It’s a brutal read.

Most people think classic literature is about grand balls or guys fighting duels in the snow. This isn't that. It’s a surgical strike on the concept of "the good life." Ivan Ilyich is a man who did everything right. He went to law school. He got the right promotions. He married a woman who looked good on his arm at dinner parties. He decorated his house with the exact curtains that screamed "I have arrived." Then, he tripped while hanging those curtains, bruised his side, and started to die.

The Problem With a "Correct" Life

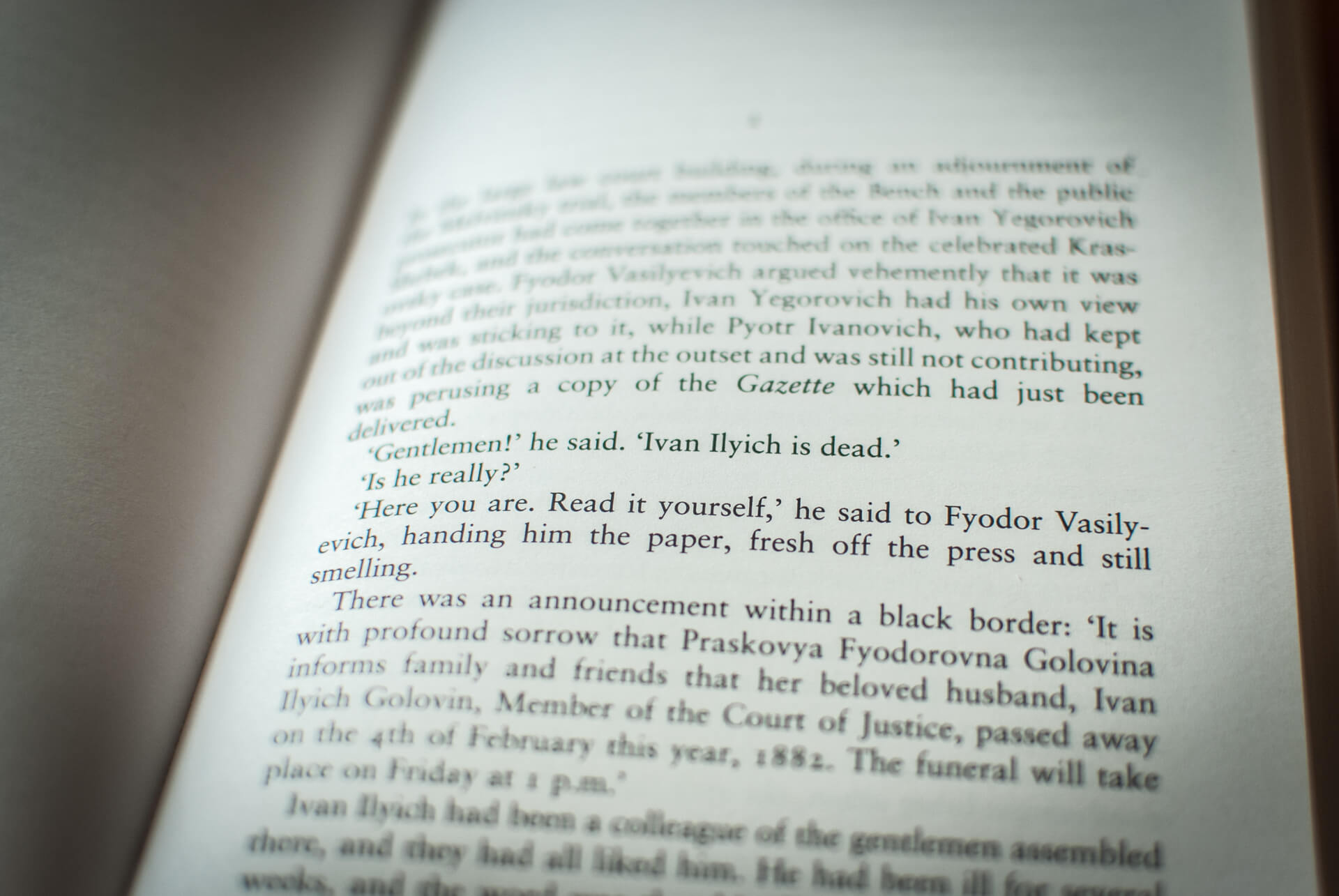

Tolstoy starts the story at the end. We see Ivan’s colleagues at his funeral, and honestly, they’re annoyed. They aren’t mourning a friend; they’re calculating who gets his job and worrying about how long they have to stay at the wake before they can go play bridge. It’s cold. It’s realistic.

You’ve probably felt this in your own office. Someone leaves, and within twenty minutes, people are eyeing their standing desk.

Ivan spent his entire existence being "comme il faut." That’s the French phrase Tolstoy uses to describe the "proper" behavior of the upper-middle class. Ivan didn't want to be a saint or a villain; he just wanted to be successful and comfortable. He lived his life on a track. He was a judge who prided himself on his "official" capacity, which is just a fancy way of saying he liked having power over people without having to care about them as human beings.

🔗 Read more: Jack Blocker American Idol Journey: What Most People Get Wrong

The tragedy isn't that Ivan is a bad guy. He isn't. He’s just a normal guy. That’s why it hurts.

When the pain in his side starts, it's just a nuisance. A dull ache. But as it grows, the doctors—who are just as detached and "official" as Ivan was in his courtroom—give him no real answers. He realizes that the decorous, polite world he built has no room for the messy, smelly, screaming reality of a dying man. His wife wants him to be quiet so she can go to the theater. His daughter is annoyed that his illness is delaying her engagement.

Why The Death of Ivan Ilyich Still Hits Hard

Tolstoy was obsessed with the "lie."

He believed that most of society is a giant performance. In the book, the only person who treats Ivan with any actual dignity is Gerasim, a peasant servant. Why? Because Gerasim is the only one who doesn’t fear death. He sees it as a natural part of life, like the seasons or the harvest. He holds Ivan’s legs up to ease his pain, not out of duty, but out of simple, unvarnished empathy.

It’s a stark contrast.

💡 You might also like: Why American Beauty by the Grateful Dead is Still the Gold Standard of Americana

On one hand, you have the "educated" elite who use fancy words to hide the fact that they’re terrified of their own mortality. On the other, you have a guy who cleans latrines and possesses more wisdom than the entire Russian judiciary.

Vladimir Nabokov, a guy who was notoriously hard to please, once said that this story is Tolstoy’s most artistic, most perfect, and most sophisticated achievement. He wasn't wrong. The pacing is claustrophobic. As the room shrinks around Ivan, the prose gets tighter. You feel the curtains, the medicine bottles, and the suffocating silk of the pillows.

The Moment of the "Black Sack"

Toward the end, Ivan has a literal and metaphorical vision. He feels like he’s being shoved into a narrow, deep black sack. He’s struggling to get to the bottom of it, but he’s held back by his own "good" life.

He realizes that his "correct" life was actually the thing that killed his soul long before his body started failing.

Think about that for a second.

📖 Related: Why October London Make Me Wanna Is the Soul Revival We Actually Needed

Tolstoy is suggesting that the more we focus on status, "pleasantness," and avoiding discomfort, the more we're actually suffocating. Ivan asks himself the most terrifying question anyone can ask on their deathbed: "What if my whole life has been wrong?"

He realizes that his only moments of true living were in his childhood—back when he felt things deeply, before he learned how to be a "judge" or a "socialite."

Getting Through the Existential Dread

If you’re reading The Death of Ivan Ilyich for the first time, or if you're revisiting it because you feel like your life is a series of Zoom calls and Amazon deliveries, here is how to actually digest it without spiraling.

- Pay attention to the physical objects. Tolstoy uses the furniture to show Ivan’s isolation. The very things he loved—the expensive chairs, the velvet—become his enemies. It’s a great reminder that you can’t take the IKEA catalog with you.

- Look at the "Official" vs. the "Human." Notice how characters switch modes. When they are being "official," they are cruel. When they are being human (like Gerasim or Ivan’s young son), they are kind.

- Don't rush the ending. The last few pages are a whirlwind of light and pain. Ivan finally finds a way out of the "sack" not by getting better, but by finally feeling pity for others instead of just for himself.

The book isn't actually a "downer," though it feels like one for 90% of the time. It’s meant to be a wake-up call. Tolstoy wrote this after his "conversion" to a form of Christian anarchism/asceticism. He wanted to strip away the bullshit of the Russian Orthodox Church and the Tsarist state. He wanted people to stop living for the "curtains" and start living for the "light."

Actionable Takeaways from Ivan's Mistakes

Reading this shouldn't just be an academic exercise. If you want to avoid ending up like Ivan (spiritually, at least), here is the roadmap Tolstoy lays out:

- Audit your "Comme Il Faut" moments. Where are you performing a role just because it’s expected? If your job or your social circle requires you to stop being a person and start being a "function," you’re in the Ivan Ilyich trap.

- Practice radical empathy. Gerasim’s power came from the fact that he wasn't afraid to look at someone else's suffering. Don't look away when things get messy or inconvenient.

- Acknowledge the inevitable. Most of our modern world is designed to make us forget we’re going to die. Tolstoy argues that by remembering it, we actually start living.

- Prioritize the "Childhood" joy. Ivan remembered the taste of a certain plum or the smell of his mother’s dress. Those were the only "real" things. Find your "real" things and stop burying them under professional milestones.

Ultimately, this novella acts as a mirror. If you find Ivan Ilyich's death annoying or depressing, you might be one of his colleagues. If you find it terrifying, you're probably Ivan. But if you find it liberating, you're starting to understand what Tolstoy was actually trying to do. He wasn't trying to scare us; he was trying to save us from a life lived in a "black sack" of our own making.

Go buy a physical copy. Put your phone in another room. Read it in one sitting. It’s only about 60 pages, but it’ll stay with you longer than any 800-page epic. Just maybe don't hang any curtains immediately afterward.