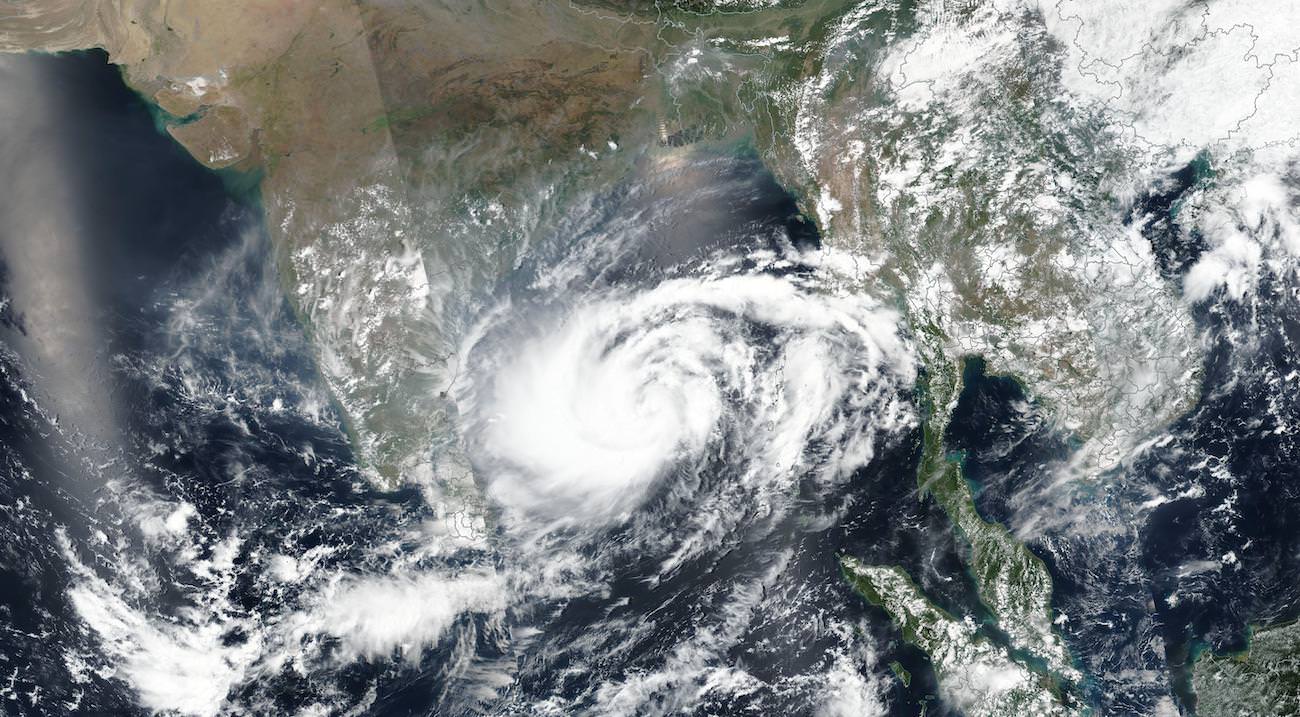

The water is warm. Too warm, honestly. When you look at a map of the Indian Ocean, the Bay of Bengal looks like a giant, inverted funnel, ready to trap anything that wanders in. It isn't just a body of water; it’s a factory. Specifically, it is the world’s most prolific factory for some of the deadliest storms on the planet. If you live in Odisha, West Bengal, or Bangladesh, a cyclone of Bay of Bengal isn't just a weather report. It’s a recurring trauma.

Most people think hurricanes in the Atlantic are the big ones. They aren't. While the Pacific sees more frequent typhoons, the Bay of Bengal holds the grim record for the highest number of fatalities caused by tropical cyclones. Why? It's a mix of geography, shallow coastal waters, and a massive population living just a few feet above sea level.

The Funnel Effect and Why the Bay is Different

Geography is destiny here. The Bay of Bengal is semi-enclosed, bordered by the Indian peninsula to the west and the Malay Peninsula to the east. When a storm starts brewing, it has nowhere to go but north. As it moves, the narrowing shape of the bay squeezes the water. This creates a massive storm surge. Imagine pushing water in a bathtub toward the corner—it has to go up. In places like the Ganges-Brahmaputra delta, that surge can travel miles inland, wiping out everything in its path.

There’s also the freshwater factor. The bay receives a staggering amount of freshwater from rivers like the Ganges and the Irrawaddy. This creates a "layer" on the surface. Since freshwater is less dense than saltwater, it doesn't mix well. This layer traps heat at the surface, providing high-octane fuel for any passing depression. You’ve basically got a pool of hot oil waiting for a match.

Why the 26-Degree Rule Matters

For a cyclone to even stand a chance of forming, the sea surface temperature (SST) needs to be at least 26.5°C. Lately, the Bay of Bengal has been blowing past that. We are seeing temperatures hit 30°C or 31°C. This leads to what meteorologists call "Rapid Intensification." A storm can go from a mild tropical depression to a Category 4 equivalent monster in less than 24 hours. We saw this with Amphan in 2020. One day it was a concern; the next, it was a catastrophe.

💡 You might also like: Obituaries Binghamton New York: Why Finding Local History is Getting Harder

Comparing the Giants: Bhola, Amphan, and Mocha

You can't talk about a cyclone of Bay of Bengal without mentioning 1970. The Bhola Cyclone remains the deadliest tropical cyclone ever recorded. Estimates suggest up to 500,000 people died. It wasn't just the wind; it was the timing. The storm hit during high tide, and the surge was over 30 feet high. It literally reshaped the politics of the region, contributing to the independence of Bangladesh.

Then there was Odisha in 1999. A "Super Cyclone" with winds of 260 km/h. It stayed over the land for hours, refusing to die. After that, India realized it couldn't keep losing thousands of people. The resulting shift in disaster management was massive. By the time Cyclone Phailin hit in 2013, the government evacuated nearly a million people. The death toll was in the dozens, not the thousands. That is progress, but the storms are getting meaner.

Recently, Cyclone Mocha in 2023 showed us a new problem. It didn't just hit the coast; it screamed into the hills of Myanmar and Bangladesh. It devastated refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar. This highlights a nuance often missed: even if we get better at evacuations, the sheer destruction of infrastructure—the "economic death"—is becoming unsustainable for developing nations.

The Science of the "Quiet" Periods

The Bay isn't always screaming. It has two peak seasons: April to June and October to December. The monsoon season in the middle actually acts as a damper. The high-level winds during the monsoon are too strong, shredding storms before they can organize. But once that monsoon withdraws, the wind shear drops. The atmosphere becomes still, humid, and ready. That’s when the real monsters wake up.

📖 Related: NYC Subway 6 Train Delay: What Actually Happens Under Lexington Avenue

Some researchers, like those at the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology (IITM), have noted that while the total number of cyclones isn't necessarily skyrocketing, the intensity is. We are seeing fewer "weak" storms and more "Extremely Severe Cyclonic Storms." Basically, the Bay is swinging for the fences every time now.

The Role of the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD)

Ever heard of the IOD? Think of it as El Niño's cousin. When the IOD is "positive," the western Indian Ocean is warmer than the east. This can actually influence how much energy is available in the Bay of Bengal. It’s a complex dance between the ocean and the atmosphere that makes seasonal forecasting a nightmare for the IMD (India Meteorological Department).

Survival and the Reality on the Ground

If you’re standing on a beach in Digha or Chittagong when a warning is issued, the "vibe" is heavy. It’s a race. The government sends out "Cyclone Mitras" (volunteers) with megaphones. They use a flag system. One flag? Be alert. Three flags? Get to the shelter. These shelters are often concrete buildings on stilts, designed to let the surge flow underneath.

But here is the thing: livestock. For a farmer in the Sundarbans, their cow is their entire life savings. Many people refuse to evacuate because they can't take their animals to the shelter. This leads to preventable deaths. New "multipurpose" shelters are now being built with ramps for cattle, which sounds like a small detail but is actually a game-changer for evacuation compliance.

👉 See also: No Kings Day 2025: What Most People Get Wrong

Misconceptions About Track Predictions

People get frustrated when a cyclone "misses" the predicted landfall. "The weatherman was wrong," they say. Kinda. Predicting a cyclone of Bay of Bengal is incredibly hard because the bay is small. In the Atlantic, a hurricane has thousands of miles to settle into a track. In the Bay, a storm might only have 400 miles before it hits land. A 10-degree wobble in direction means the difference between hitting a major city like Kolkata or hitting an uninhabited mangrove forest.

The "Cone of Uncertainty" isn't a suggestion; it's a mathematical reality. If you're anywhere in that cone, you're in the crosshairs.

The Mangrove Shield

Nature actually provided a defense system: The Sundarbans. This massive mangrove forest acts as a literal physical barrier. The dense roots and trees break the force of the wind and slow down the storm surge. However, as we cut down mangroves for shrimp farming and development, we are literally tearing down our own walls. Every acre of mangrove lost is an increase in the height of the next storm surge that hits a village.

What You Need to Do Next

If you live in or are traveling to a high-risk zone, don't wait for the rain to start. Cyclones are predictable in their arrival but unpredictable in their behavior.

- Check the IMD or BMD sites directly. Don't rely on forwarded WhatsApp messages. Look for the "Track Forecast" and the "Wind Warning" maps.

- Understand the surge, not just the wind. Most people die from drowning, not from houses blowing down. If you are told to evacuate because of a 5-meter surge, go. Even if the wind doesn't feel "that bad" yet.

- Audit your emergency kit. You need a battery-powered radio. When the towers go down—and they will—your smartphone is just a glass brick. You need those AM/FM broadcasts for official updates.

- Waterproofing is key. Put your ID, property deeds, and some cash in heavy-duty Ziploc bags. It sounds simple, but losing your identity documents in a flood can stall your recovery for years.

The Bay of Bengal will always produce storms. It's the nature of the geography. But as the ocean warms and the stakes get higher, the difference between a "weather event" and a "national tragedy" comes down to how much we respect the science behind the surge. Stop looking at the sky and start looking at the sea level. That's where the real danger lies.

Immediate Action Item: Download the 'Sachet' app if you are in India or monitor the 'BMD' official portal in Bangladesh. These provide localized, real-time alerts that bypass the lag of traditional news media. If a depression is marked in the central bay, check your local shelter route immediately, as the window for safe movement closes 12 hours before landfall.