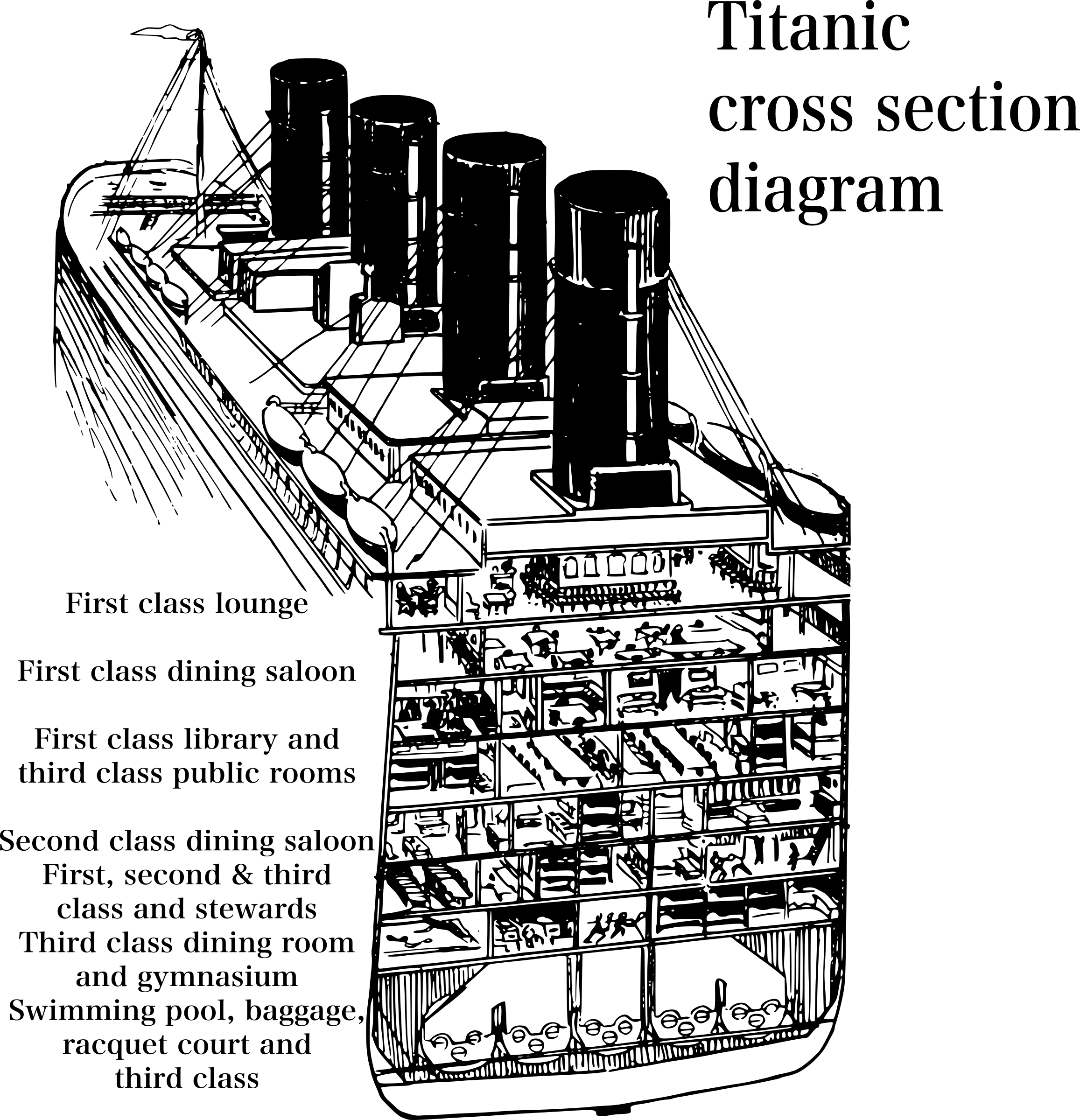

Ever looked at a drawing of a ship and felt like you were staring at a giant, steel honeycomb? That's basically what you get when you study a cross section of Titanic. It wasn't just a boat; it was a floating, vertical class system wrapped in 52,000 tons of steel. If you slice that ship down the middle, you don't just see engines and cabins. You see exactly how the Edwardian era thought about human value.

It’s easy to get lost in the romance of the Grand Staircase. But the real story is in the guts. Look at a technical profile of the Olympic-class liners. You’ll notice the "watertight" bulkheads don't go all the way up. That’s the design flaw everyone talks about, but seeing it in a cutaway view makes you realize how crazy it actually was. They stopped at E-Deck. Why? Because the designers at Harland and Wolff wanted the public rooms to be wide and open. They prioritized aesthetics over the physical height of the safety walls.

The Vertical Reality of the Cross Section of Titanic

If you’re looking at the ship from the side, Third Class is buried. It's way down there. While First Class passengers were enjoying the breeze on the Boat Deck, the "steerage" passengers were literally living next to the vibration of the reciprocating engines.

The ship had ten decks.

Ten.

Think about that.

The Boat Deck was the top. Then you had A through G, followed by the Orlop decks and the tank top. In a cross section of Titanic, the tank top is the very bottom. That’s where the 29 boilers lived. It was a hellscape of coal dust and fire. Men called "black gang" stokers worked in those shifts, shoveling 600 tons of coal a day just to keep the lights on and the propellers spinning. When people look at the blueprints today, they often skip the boiler rooms, but that's where the ship's heart—and its eventual doom—really lived.

The Scotch boilers were massive. They were about 15 feet in diameter. In a cutaway, they look like giant drums packed into the lowest reaches of the hull. Above them, the layers of luxury started to pile up. It’s almost like a layer cake where the frosting gets more expensive the higher you go.

Space as a Luxury

Most people don't realize how much of the ship was actually empty space or cargo. The "G Deck" featured the mail room and the squash court. Imagine playing squash while in the middle of the Atlantic. It sounds refined, but when you see it on a map of the ship's interior, it's positioned precariously low.

📖 Related: Hairstyles for women over 50 with round faces: What your stylist isn't telling you

First Class passengers had "Parlor Suites." These were insane. They had private promenades. On a cross-section diagram, these are the wide-open spaces on B-Deck. Contrast that with the cramped, four-to-six berth cabins in Third Class. In Third Class, you didn't get a private bathtub. In fact, for the roughly 700 passengers in steerage, there were only TWO bathtubs. Not two per room. Two for the whole category.

The Fatal Flaw in the Architecture

We have to talk about the bulkheads again. In any cross section of Titanic, you can see the 15 transverse watertight bulkheads. They divided the hull into 16 compartments. The tragedy wasn't that they weren't watertight; they were. The problem was that they were "open at the top," sort of like an ice cube tray.

If you tilt an ice cube tray, the water spills from one square to the next. That’s precisely what happened on April 14, 1912. The iceberg sliced a series of holes along the starboard side. Because the ship started to pull down by the head, the water simply rose over the top of bulkhead E and flowed into the next section.

Thomas Andrews, the ship's designer, knew this immediately. When he looked at the blueprints in the wireless room after the collision, he saw the "mathematical certainty" of the sinking. He knew that once five compartments were breached, the weight would pull the bow down far enough to let the "ice cube tray" effect take over.

Why the Engines Matter

Looking at the mechanical cross section, the engine room was a masterpiece of 1912 technology. You had two four-cylinder triple-expansion engines. These things were the size of houses. They powered the two wing propellers. Then, in the middle, you had a low-pressure Parsons turbine that used exhaust steam to turn the center propeller.

It was incredibly efficient for the time.

But it was also heavy.

The weight of these engines meant that when the ship broke in two—which we now know happened thanks to Robert Ballard’s 1985 discovery—the stern didn't just bob there. The engines were so heavy they helped drag the broken pieces to the bottom at high speeds.

👉 See also: How to Sign Someone Up for Scientology: What Actually Happens and What You Need to Know

The Grand Staircase vs. The Scotland Road

In the center of the First Class section was the Grand Staircase. It was topped by a wrought iron and glass dome. This allowed natural light to filter down to D-Deck. It’s the image everyone has from the James Cameron movie.

But look further down.

On E-Deck, there was a long, functional hallway that ran almost the entire length of the ship. The crew called it "Scotland Road," named after a famous street in Liverpool. This was the service artery of the ship. While the wealthy were walking down oak-carved stairs, the stewards and firemen were sprinting through Scotland Road to get from one end of the 882-foot ship to the other.

In a cross section of Titanic, you can see how Scotland Road was a bottleneck. During the sinking, this hallway became a chaotic maze for Third Class passengers trying to find their way to the surface. Many got lost in the labyrinth of the ship's "bones" before they ever reached a lifeboat.

Misconceptions About the Hull

There's a common myth that the steel was "garbage." Honestly, that's a bit of an oversimplification. For 1912, the steel was top-tier. However, modern metallurgy tests on fragments recovered from the debris field show that the steel had a high sulfur content. This made it "brittle" in freezing water.

Instead of bending when the iceberg hit, the steel plates shattered or "popped" their rivets. If you look at a cross section of the hull’s riveting, you see three rows of rivets in the areas of highest stress. But even three rows couldn't hold back the pressure of the Atlantic once that brittle fracture started.

The Coal Bunker Fire

Here is a detail that doesn't show up in every drawing: Coal Bunker Number 6. There was a smoldering fire in that bunker since the ship left Belfast. In a cross-section view, this bunker is right against one of the main watertight bulkheads. Some historians, like Senan Molony, argue that the heat from this fire—reaching up to 1000 degrees—weakened the steel bulkhead. When the water finally hit that specific bulkhead, it may have failed faster because it had been "cooked" for days.

✨ Don't miss: Wire brush for cleaning: What most people get wrong about choosing the right bristles

Anatomy of the Sinking

When the ship broke, it didn't just snap like a twig. The cross section of Titanic at the moment of the break shows the "double bottom" hull acting like a hinge. The top decks tore apart first because steel is better at handling compression than tension. The bottom of the ship—the double hull—held on for a few seconds longer, acting as a pivot point before finally snapping.

This left the stern to bob for a moment before the weight of the refrigerated cargo holds and the remaining machinery filled with water.

Realities of the Debris Field

If you go to the bottom of the ocean today, the cross section of the ship is exposed. The bow is buried deep in the mud, but the "tear" where the ship broke allows us to see the internal decks like a dollhouse that’s been kicked over. You can see the porcelain bathtubs, the bed frames, and even the remains of the elevators.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs

If you want to truly understand the layout of the ship beyond a simple 2D drawing, there are a few things you can do to get a "pro" level of knowledge:

- Study the Deck Plans: Don't just look at the side view. Look at the "overhead" for each deck. It shows you that the ship was a maze of corridors designed to keep classes from ever meeting.

- Visit a Museum: The Titanic Belfast museum has floor-to-ceiling projections that basically walk you through a digital cross section of Titanic. It’s the closest thing to being there.

- Research the "Olympic" sister ship: Since the Titanic's sister, the Olympic, had a long career, there are many more actual photographs of its internal structure. Since they were nearly identical, these photos provide the "color" to the Titanic's black-and-white blueprints.

- Check out 3D Scans: Recent 4K "digital twins" created by Magellan Ltd show the ship in its entirety without the water. This allows you to see the cross-section of the wreckage in ways that were impossible even five years ago.

The ship was a marvel, but it was also a warning. When you look at the architecture, you see the arrogance of a world that thought it had finally conquered nature. Every rivet and every cabin on that cross section represents a choice—usually a choice that favored luxury over the cold, hard reality of the North Atlantic.