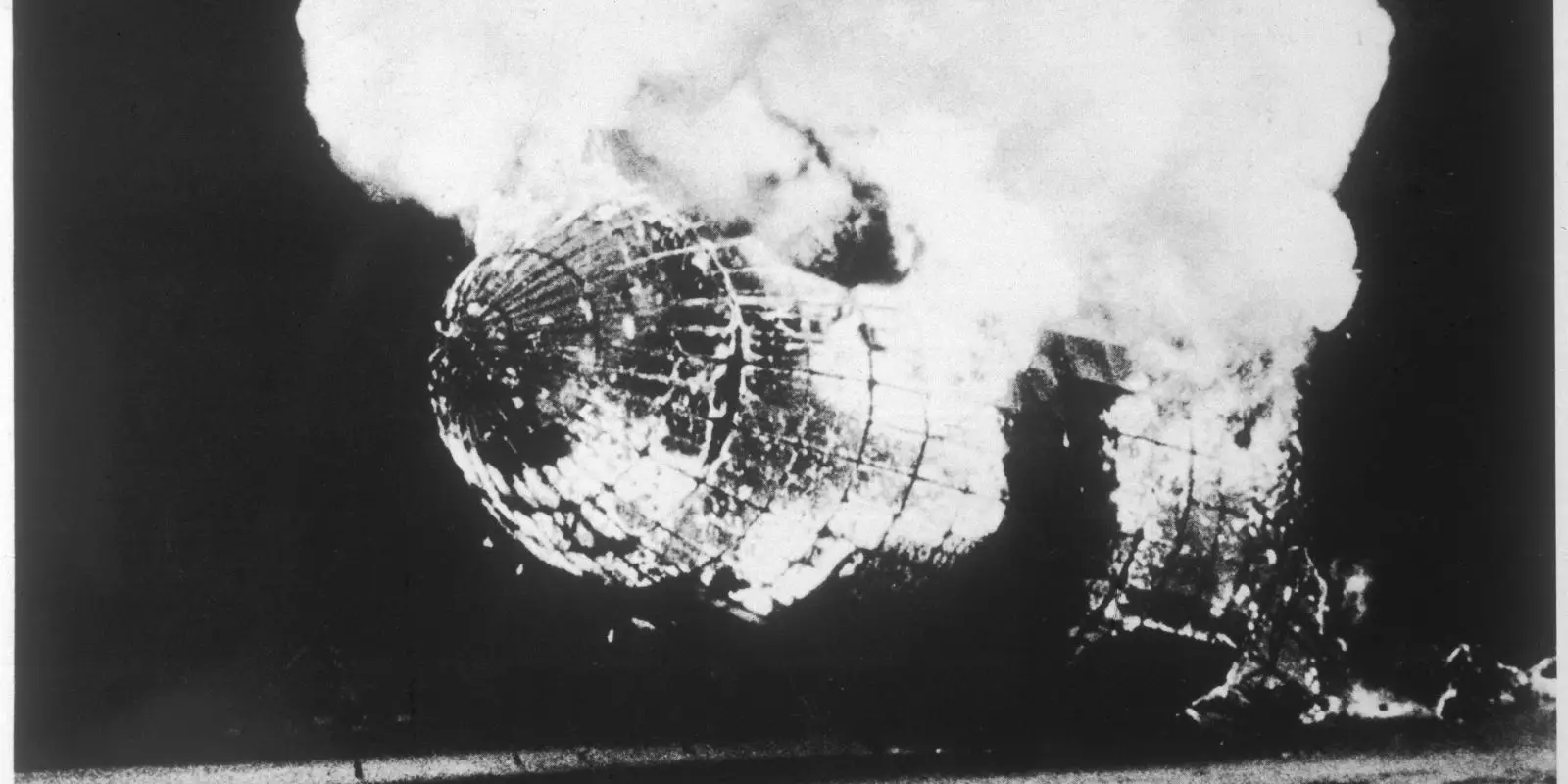

Everyone thinks they know the footage. You see the massive silver cigar-shaped ship drifting toward a mooring mast in New Jersey, and then—boom. A sudden blossom of fire near the tail, the skin of the ship vanishing in seconds, and that agonizingly slow descent to the ground while Herb Morrison’s voice cracks in the background. But here’s the thing: most people watching a crash of the hindenburg video today are actually seeing a composite of history, edited and re-timed for modern screens.

The reality was much faster. And much weirder.

It wasn't just one guy with a camera. There were four professional newsreel crews stationed at Lakehurst, New Jersey, on May 6, 1937. Pathe News, Paramount News, Movietone, and Universal were all there. They weren't expecting a disaster. They were bored. The ship was three hours late because of bad thunderstorms. When the Hindenburg finally appeared through the clouds, it was a routine "celebrity" arrival.

Then everything went wrong.

The Footage We Almost Didn't Have

If you look closely at the most famous crash of the hindenburg video clips, you'll notice different angles. Some are tight on the hull; others show the whole airfield. The cameramen were professionals, but they were human.

Al Gold of Fox Movietone News actually missed the very first spark because he was reloading his camera. Think about that. One of the most significant moments in 20th-century journalism almost went unrecorded because of a physical roll of film.

It was a nightmare to film. The fire was fueled by hydrogen, which burns nearly invisible in daylight, but the Hindenburg was covered in a cellulose acetate butyrate dope infused with aluminum flakes. Basically, the ship was wrapped in rocket fuel. That’s what created the bright, roaring orange glow that showed up so vividly on black-and-white film.

Why the audio sounds so strange

You've heard the "Oh, the humanity!" line. Everyone has. But if you watch an original crash of the hindenburg video, you might notice the sound doesn't perfectly sync.

📖 Related: Trump Derangement Syndrome Definition: What Most People Get Wrong

That's because Herb Morrison wasn't filming. He was recording on a Presto Direct-to-Disk recorder for WLS radio in Chicago. This was a massive, clunky machine that cut grooves into a green acetate disk in real-time. When the explosion happened, the shockwave actually caused the recording needle to jump and gouge the disk.

When you hear his voice pitch up and down, that’s not just emotion—it’s the physical trauma to the recording equipment. For years, documentary filmmakers have slowed down the footage or sped up the audio to make them match, creating a "movie" version of a real-life tragedy that never actually existed in that format at the time.

What the Cameras Missed (and What They Caught)

The fire took exactly 34 seconds to consume the ship.

Thirty-four seconds.

In that half-minute, the newsreel cameras captured things that still spark debates among forensic engineers today. One specific crash of the hindenburg video angle from the port side shows a flutter in the outer skin just before the fire breaks out. This has led experts like Addison Bain, a former NASA hydrogen manager, to argue that the spark didn't start inside the gas cells but on the highly flammable skin itself.

Others disagree. They point to the way the ship settled.

If you watch the footage carefully, the stern hits the ground first. Why? Because the rear gas cells 4 and 5 were the first to go. The bow actually stayed lofted for a few seconds, acting like a chimney. This created a "venturi effect" where the fire roared through the central corridor, essentially turning the luxury airship into a massive blowtorch pointed at the sky.

👉 See also: Trump Declared War on Chicago: What Really Happened and Why It Matters

- The "Jumpers": If you look at the lower frame of the Universal newsreel, you can see dark specks falling from the promenade windows. Those are people. Some survived the jump; others didn't.

- The Ground Crew: Notice the men running away from the mast. They were "linesmen" holding the heavy manila ropes. When the ship ignited, they were standing directly under 7 million cubic feet of burning hydrogen.

- The Structure: Watch how the duralumin frame glows. It doesn't just melt; it crumples like tissue paper.

The Myth of the "Complete" Record

Kinda crazy to think about, but we don't have a video of the start of the fire.

We have the split-second after it became visible, but nobody was pointed at the exact vent or wire where the discharge happened. This gap in the crash of the hindenburg video record is why conspiracy theories lived for so long. Was it a bomb? Was it an anti-Nazi saboteur?

The FBI and the Luftwaffe both did investigations. They looked at the film frame by frame. Ultimately, the consensus leaned toward an electrostatic discharge—a spark of static electricity—caused by the ship being "grounded" by its landing ropes while the hull remained charged from the recent storm.

Basically, the ship became a giant capacitor. When the ropes hit the wet ground, the "juice" moved, a spark jumped, and the leaking hydrogen (which had likely pooled under the upper fin) went up.

Modern Restoration and What it Reveals

Recently, high-definition scans of the original 35mm newsreel negatives have surfaced. Seeing a crash of the hindenburg video in 4K is a completely different experience than watching the grainy, high-contrast versions we saw in history class.

You can see individual faces in the windows. You can see the sheer scale of the ground crew. Honestly, it makes the survival rate even more shocking. Out of 97 people on board, 62 survived. Looking at the ferocity of the fire on film, you’d swear nobody could have walked away.

But because the fire burned up so quickly, many passengers literally walked out of the gondola once it hit the sandy soil of New Jersey.

✨ Don't miss: The Whip Inflation Now Button: Why This Odd 1974 Campaign Still Matters Today

How to Analyze the Footage Yourself

If you’re looking at a crash of the hindenburg video for research or just out of a sense of historical curiosity, don't just watch the flames. Look at the context clues that the newsreels provide.

- Check the flags: Notice the wind direction. The ship was struggling to level off against a shifting breeze.

- Look at the water ballast: In several clips, you can see water being dumped from the nose just before the explosion. The crew was trying desperately to keep the ship level as it lost buoyancy in the rear.

- The "Grounding" Ropes: Find the shot where the ropes hit the dirt. That is the "T-minus zero" moment for the static discharge theory.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs

If you want to go deeper than just a YouTube search, there are better ways to experience this history.

- Visit the Source: The National Archives holds the highest-quality copies of the newsreels. If you’re doing serious research, don't rely on "restored" versions which often use AI to interpolate frames (this can actually "hallucinate" details that weren't in the original film).

- Compare the Perspectives: Watch the Pathe version alongside the Movietone version. The different focal lengths used by the cameramen give a much better sense of the 3D space of the disaster.

- Read the Navy Reports: The Lakehurst Naval Air Station kept meticulous logs that sync up with the time stamps on the film. Reading the logs while watching the footage provides a "God-view" of the disaster.

- Study the Survivor Accounts: Read the testimony of Margaret Mather or Joseph Spah. When you match their descriptions of "a sharp report like a pistol shot" to the visual of the first flame on the crash of the hindenburg video, the physics of the disaster starts to make a lot more sense.

The Hindenburg wasn't the deadliest airship accident—that honor goes to the USS Akron, which crashed into the ocean. But the Hindenburg is the one we remember because we have the tape. It was the first "global" disaster captured on camera and broadcast to the masses. It ended the era of the zeppelin not because it was the only crash, but because it was the only one that people had to watch with their own eyes.

Even today, that grainy black-and-white film serves as a brutal reminder of how quickly "state of the art" technology can turn into a skeleton of glowing metal.

Next Steps for Deep Research:

Check out the Smithsonian National Postal Museum’s digital exhibit on Hindenburg mail. They have recovered envelopes that were actually on board the ship during the crash. You can see the scorch marks on the paper and correlate the damage to where the mail bags were stored in the hull relative to the fire seen in the footage. For a technical deep dive, look up the "Static Spark Theory" papers published by the hydrogen safety community; they use the newsreel footage as primary evidence for modern gas safety protocols.