If you stand in the middle of La Fortuna today, surrounded by lush gardens and the smell of roasting coffee, it’s hard to imagine the mountain in front of you was once a killer. For centuries, people living in the shadow of the peak thought it was just another hill. They called it "Cerro Arenal." They hiked it. They farmed near it. Then, on a Monday morning in July 1968, the ground started shaking in a way that didn't feel like a normal Costa Rican tremor. The Costa Rica Arenal volcano eruption didn't just change the geography of the northern lowlands; it basically invented the modern tourism industry of the country while leaving a scar that's still visible if you know where to look.

The mountain woke up hungry.

Actually, saying it "woke up" is kinda an understatement. It blew its side out. On July 29, 1968, at roughly 7:30 AM, a massive explosion tore through the western flank. It wasn't a slow leak of lava. It was a lateral blast—the kind of violent event that sends "nuées ardentes" or pyroclastic flows racing down the slopes at hundreds of miles per hour. People in the nearby villages of Tabacón and Pueblo Nuevo didn't have a chance. If you've ever seen those photos of the aftermath, it looks like a moonscape. Gray. Ash-choked. Total silence where there used to be birds and cattle.

What Actually Happened During the 1968 Costa Rica Arenal Volcano Eruption

Scientists from the Smithsonian Institution and the Universidad de Costa Rica have spent decades piecing together the timeline. It wasn't just one pop. The activity lasted for days. The initial blast was followed by several more large explosions over the next three days, tossing "bombs"—huge chunks of glowing rock—into the air. Some of these impact craters are still visible today along the 1968 Trail in the National Park.

Honestly, the tragedy was rooted in a lack of history. Before 1968, the last major activity was estimated to be around the year 1500. There was no living memory of the mountain being a volcano. Local farmers were caught completely off guard because, to them, Arenal was just a backdrop, not a threat. By the time the dust settled, nearly 80 people were dead, and 45 square kilometers were buried under ash and stone.

The heat was intense. We're talking about temperatures inside those pyroclastic clouds reaching over 500 degrees Celsius. It incinerated everything in its path.

✨ Don't miss: Magnolia Fort Worth Texas: Why This Street Still Defines the Near Southside

The Shift from Destruction to Attraction

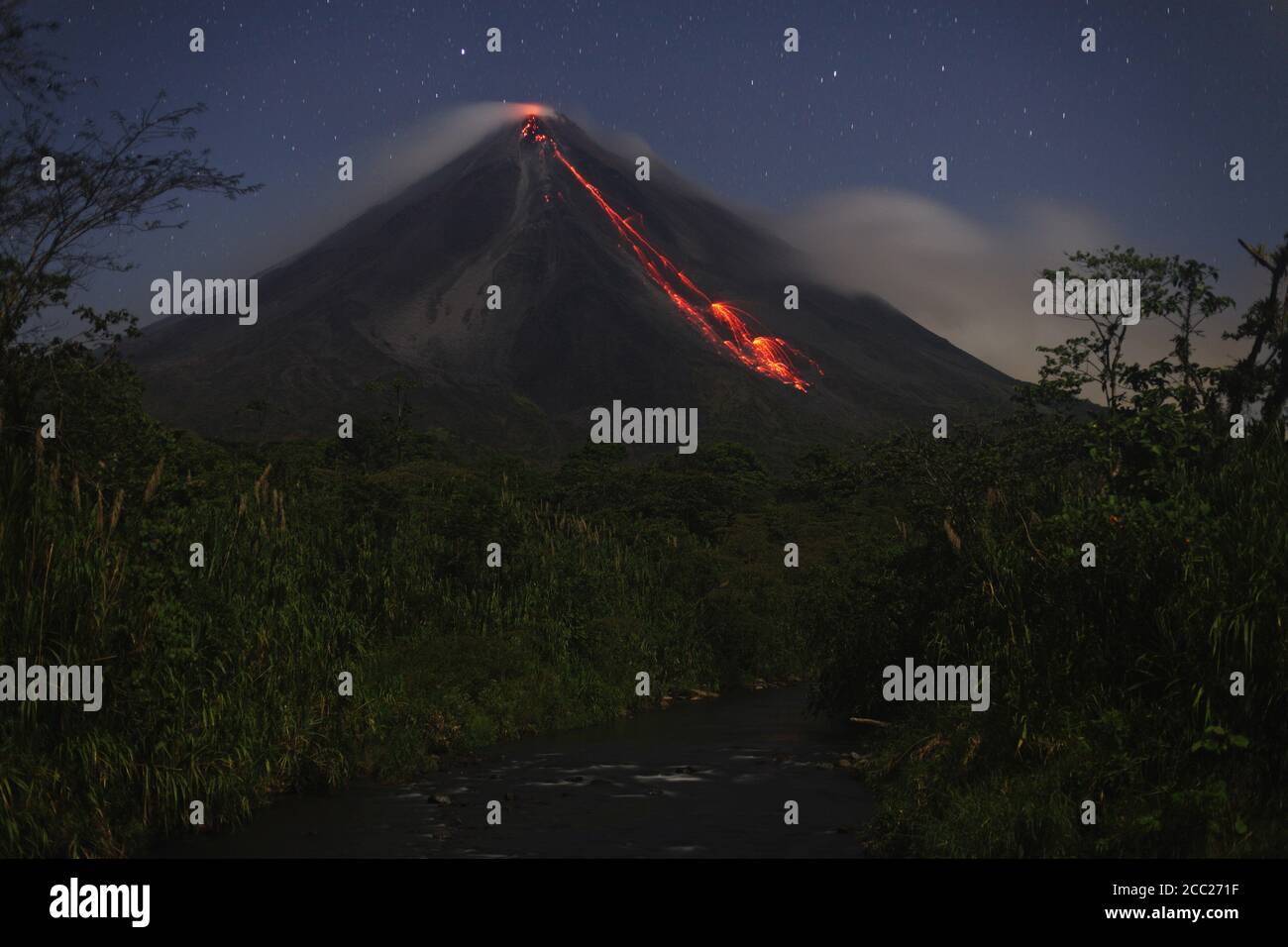

Something weird happened after the tragedy. Usually, when a volcano kills dozens of people, everyone moves away. But Arenal stayed active. For the next 42 years, it became one of the most active volcanoes in the world. It was a constant show. You’d sit in a hot spring at night with a cocktail, looking up to see red-hot boulders tumbling down the side like glowing marbles.

This is what built La Fortuna.

Before the Costa Rica Arenal volcano eruption, the town was a sleepy agricultural outpost. Afterward, it became a global magnet. Geologists came first. Then the backpackers. Then the luxury resorts. Everyone wanted to see the fire. It’s a strange irony that the very event that destroyed two towns ended up creating the economic engine of the entire province of Alajuela.

The Science of the "Sleeping" Giant

People always ask me: "Is it going to blow again?"

Well, technically, it’s still active. But it’s in a resting phase. Since 2010, the "lava show" has stopped. No more glowing rocks at night. No more plumes of smoke visible from the town square. According to the OVSICORI (the Volcanological and Seismological Observatory of Costa Rica), the volcano is currently "resting," though they still monitor it with seismometers and gas sensors 24/7.

🔗 Read more: Why Molly Butler Lodge & Restaurant is Still the Heart of Greer After a Century

- Status: Active, but dormant phase.

- Height: 1,670 meters (roughly).

- Type: Stratovolcano (the classic cone shape).

- Last Major Activity: 2010.

It’s a "subduction zone" volcano. Basically, the Cocos Plate is sliding under the Caribbean Plate, melting rock into magma that eventually finds its way up. It’s the same process that created the whole Central American Volcanic Arc. If you look at a map, you’ll see Arenal sits right on a line with Poás, Irazú, and Turrialba. It's all part of the same fiery family.

Navigating the Arenal 1968 Trail

If you want to understand the scale of the Costa Rica Arenal volcano eruption, you have to hike the lava fields. There are two main spots: the Arenal Volcano National Park and the private "Arenal 1968" park. Honestly, the 1968 trail is often better for seeing the actual impact. You’re walking on jagged, black basaltic rock that used to be liquid fire.

The silence up there is heavy.

As you climb the old lava flows, you notice how nature is slowly taking it back. Lichens grow first, breaking down the rock. Then ferns. Then small trees. It’s primary succession happening in real-time. You can see the exact line where the forest stopped being burned and where the new growth begins.

Why the 1968 Eruption Still Matters in 2026

It matters because it taught Costa Rica how to handle natural disasters. The National Emergency Commission (CNE) basically grew up alongside the volcano's active years. Today, there are strict "hazard zones" where you aren't allowed to build. If you look at the hotels, they are all positioned outside the high-risk paths identified by geologists.

💡 You might also like: 3000 Yen to USD: What Your Money Actually Buys in Japan Today

The 1968 event also created the hot springs. The magma chamber is still down there, heating up the groundwater that flows through the Tabacón River and other nearby streams. Without that 1968 shift in the mountain's plumbing, you wouldn't have the world-class thermal spas that define the region today.

Misconceptions About the Eruption

A lot of people think the volcano is "extinct." That’s a mistake. A big one. Geologists classify a volcano as extinct only after thousands of years of silence. Arenal has only been quiet for about 15 years. That's a blink of an eye in geologic time.

Another myth is that you can hike to the crater. You can't. It’s illegal and incredibly dangerous. The gases at the top—mostly sulfur dioxide—can be toxic, and the ground is unstable. The park rangers take this very seriously. If you try to summit, you’re not just risking a fine; you’re risking your life on a mountain that has a history of sudden, violent outbursts.

Planning a Visit to the Site

If you're heading to the area to see the remnants of the Costa Rica Arenal volcano eruption, do it right. Don't just look at it from your hotel balcony.

- Hire a local guide. Seriously. They have stories passed down from grandparents who remember the 1968 blast. They can point out the "breadcrust bombs" (rocks that cooled faster on the outside than the inside) that you’d otherwise just step over.

- Go early. The clouds usually roll in by 10 AM. If you want to see the "scar" on the western side where the 1968 eruption happened, you need the morning light.

- Check the Seismograph. Some visitor centers have displays showing real-time seismic activity. It’s a humbling reminder that the mountain is breathing.

- Visit the Tabacón area. This was ground zero. Seeing the luxury resorts there now is a bizarre contrast to the historical photos of the ash-covered wasteland.

The 1968 event was a tragedy that morphed into a miracle for the country's economy. It’s a place where you can see the sheer power of the Earth and the resilience of a community that refused to leave. Even though the lava isn't flowing right now, the energy of that 1968 morning is still baked into the very ground you walk on.

Essential Next Steps for Travelers

When you arrive in La Fortuna, prioritize a visit to the Arenal 1968 Volcano View and Lava Trails. This private reserve offers the best perspective on the "flow" path. Plan to spend at least three hours here. Wear sturdy, closed-toe shoes; the volcanic rock is sharp and will tear up flimsy sneakers. After the hike, head to one of the thermal rivers—like the free "El Chorro" spot near Tabacón—to feel the geothermal heat for yourself. Finally, stop by the small museum in the National Park visitor center to see the black-and-white photos of the original eruption. It provides the necessary context to appreciate the green paradise you see today.