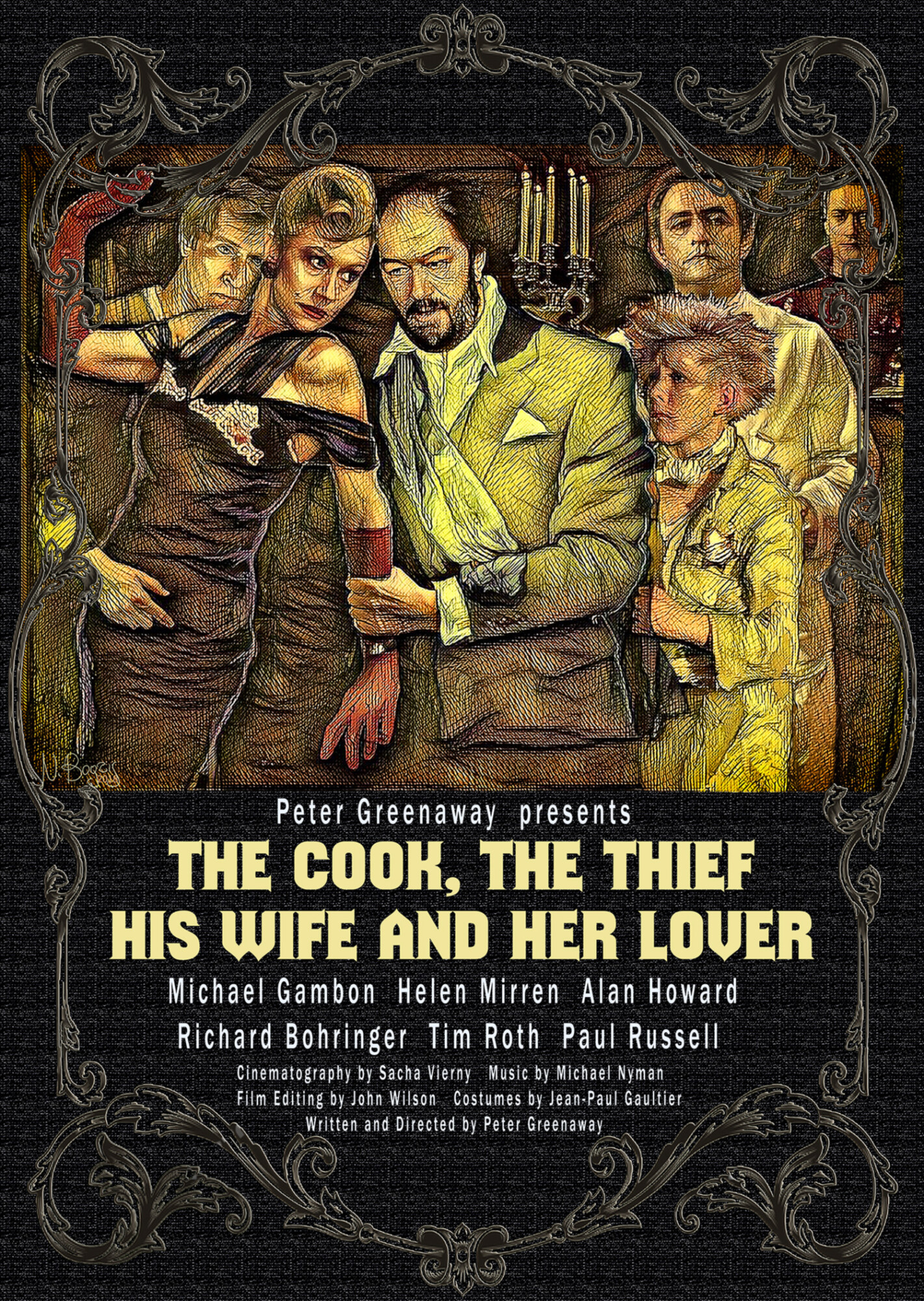

Peter Greenaway’s 1989 masterpiece, The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover, is a lot to take in. Honestly, "a lot" is an understatement. It’s a sensory assault. If you’ve seen it, you probably remember the red. That deep, oppressive, blood-like crimson of the dining room that seems to bleed off the screen and into your living room.

It’s a film about eating. It’s a film about sex. But mostly, it’s a film about the absolute, disgusting rot of power.

Back in 1989, it shocked everyone. Critics didn't know whether to hail it as a work of high art or condemn it as high-brow pornography. Miramax, led by the Weinsteins at the time, had to navigate a literal war with the MPAA over its X rating. They eventually released it unrated because no one wanted to cut a single frame of Greenaway’s meticulously composed nightmares.

What is The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover actually about?

At its simplest, it’s a revenge story. We have Albert Spica, played by a terrifyingly volatile Michael Gambon. He’s the "Thief," though he prefers the term "businessman." He’s a coarse, violent mobster who has taken over a high-end French restaurant called Le Hollandais. Every night, he drags his entourage and his refined, silent wife, Georgina (Helen Mirren), to the restaurant to gorge themselves and bully the patrons.

Then there’s the Cook. Richard (Richard Bohringer) is the silent observer, the artist who runs the kitchen. He sees everything but says little.

The plot kicks into gear when Georgina locks eyes with a quiet bookseller named Michael (Alan Howard) at a nearby table. They begin an affair, literally under Albert's nose, facilitated by the Cook who hides them in various larders and cold storage rooms. It’s beautiful, it’s desperate, and it’s doomed. When Albert inevitably finds out, the movie shifts from a dark comedy of manners into a full-blown Jacobean tragedy.

And then comes the ending. The "big" scene. You know the one. If you don't, just know it involves a very specific kind of dinner guest.

🔗 Read more: Shamea Morton and the Real Housewives of Atlanta: What Really Happened to Her Peach

The look of the thing

Greenaway didn't just film a play. He worked with Jean-Paul Gaultier on the costumes. Think about that for a second. The man who dressed Madonna in a cone bra designed the color-coded outfits for this movie. Every room in the restaurant has a specific color palette. The kitchen is green. The dining room is red. The bathrooms are a blinding, sterile white. The parking lot is blue.

The crazy part? When the characters move from one room to another, their clothes literally change color to match the room. Georgina’s dress shifts from white in the bathroom to red in the dining room. It’s a theatrical trick that reminds you, constantly, that you are watching a constructed reality. It’s not "real" life; it’s a painting that breathes.

Why Michael Gambon's performance still haunts us

Before he was the wise, twinkling Dumbledore, Michael Gambon was the most loathsome man in cinema. Albert Spica is a monster. He’s loud. He’s crude. He’s obsessed with bodily functions. He’s a man who knows the price of everything and the value of nothing.

Gambon plays him with this terrifying, unpredictable energy. One minute he’s laughing at a cruel joke, the next he’s shoving a fork into someone’s cheek. It’s a performance that anchors the film. Without a villain this repulsive, the ending wouldn't feel like justice. It would just feel like cruelty.

Mirren, on the other hand, is all internal. She plays Georgina as a woman who has learned to disappear while standing in plain sight. Her transformation from a victim to a cold-blooded architect of revenge is one of the best arcs in 80s cinema. She’s the heart of The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover, providing the soul in a world that seems to have lost it.

The politics of the plate

You can't talk about this movie without talking about Margaret Thatcher. Seriously.

💡 You might also like: Who is Really in the Enola Holmes 2 Cast? A Look at the Faces Behind the Mystery

Greenaway has been vocal about his disdain for the Thatcher era in the UK. Many critics view Albert Spica as a surrogate for the "nouveau riche" of the 1980s—people who gained immense wealth and power but lacked any shred of culture, empathy, or taste. They consume. They take. They destroy.

The restaurant is a microcosm of a decaying society where the greedy sit at the head of the table while the artists and the thinkers hide in the pantry. It’s a harsh critique. It’s cynical. But in a world where corporate greed still dominates the headlines, it feels remarkably fresh.

The controversy that wouldn't die

When the film hit theaters, it was a lightning rod. Siskel and Ebert famously debated it. Roger Ebert gave it four stars, calling it "uncompromising." He saw the beauty in the brutality. Others saw it as an exercise in "look at how edgy I am" filmmaking.

The X rating was the biggest hurdle. In the late 80s, an X rating was a death knell for commercial success. It meant most newspapers wouldn't carry your ads and many theaters wouldn't show your film. By releasing it unrated, Miramax helped pave the way for the NC-17 rating, though that’s a whole other mess of cinematic history.

Is it "gross"? Yeah, sometimes. There are scenes involving rotting meat and human waste that will make your stomach turn. But Greenaway isn't doing it for cheap thrills. He’s using disgust to make a point about the physical reality of our existence. We are all just meat, in the end.

How to watch it today

If you’re planning on sitting down with The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover tonight, maybe don't order a heavy dinner.

📖 Related: Priyanka Chopra Latest Movies: Why Her 2026 Slate Is Riskier Than You Think

- Check the version: Make sure you're watching the full, uncut version. Some older TV edits chopped the movie to ribbons, ruining the pacing and the visual impact.

- Focus on the music: The score by Michael Nyman is incredible. It’s repetitive, haunting, and builds tension like a tightening wire. The main theme, "Memorial," is a masterclass in minimalist composition.

- Look at the background: The film is packed with art history references. The massive painting in the dining room is Frans Hals' The Banquet of the Officers of the St George Militia Company in 1616. It’s not just decoration; it’s a mirror to the chaos happening at Albert’s table.

The lasting legacy of a 1989 fever dream

There aren't many movies like this anymore. Big, bold, unapologetically intellectual movies that aren't afraid to be repulsive.

We see its influence in the work of directors like Wes Anderson—who clearly took notes on the symmetrical framing and color palettes—and Ari Aster, who uses similar levels of "beautiful dread." But Greenaway's film remains singular. It’s a feast that leaves you feeling full and slightly nauseous at the same time.

It reminds us that cinema can be more than just "content." It can be a challenge. It can be a painting. It can be a protest.

Actionable insights for the cinephile

If you want to truly appreciate the depth of this film, try these steps:

- Watch a Greenaway interview: Look up Peter Greenaway’s lectures on the "death of cinema." He’s a provocateur who believes film should stop trying to be like books and start being like paintings. It puts the movie in a whole new light.

- Compare it to Jacobean Drama: Read up on 17th-century "revenge tragedies" like The Revenger's Tragedy. You'll see exactly where Greenaway got his inspiration for the heightened language and the bloody finale.

- Analyze the color shifts: On a second watch, pay close attention to the transitions between rooms. Notice how the lighting and costume colors change the mood before a single line of dialogue is spoken. It’s a masterclass in visual storytelling.

The film is a hard watch, but it’s an essential one. It’s a reminder that sometimes, the only way to deal with a monster is to give them exactly what they’ve always wanted—until it destroys them.

Explore the work of costume designer Jean-Paul Gaultier and composer Michael Nyman to see how their contributions defined the 1980s avant-garde aesthetic. Understanding the collaborative nature of this film is key to grasping why it remains a landmark of independent cinema over thirty years later.