Ever looked at a drop of pond water and realized it's actually a bustling metropolis of alien-looking creatures? That's the magic of the compound microscope light microscope. Honestly, most people haven't thought about these things since high school biology, which is a shame because they are basically the unsung heroes of modern medicine and science. We aren't just talking about plastic toys here. We’re talking about the precision instruments that helped Robert Hooke first coin the term "cell" and enabled Louis Pasteur to prove that germs—not "bad air"—make us sick.

It’s easy to get distracted by the massive, multi-million dollar electron microscopes that can see individual atoms. But for most of us, and even for most clinical labs, the light-based compound version is the workhorse. It's accessible. It's real-time. You're seeing actual light bouncing off or passing through a specimen, not a computer-generated reconstruction of electrons. There is something fundamentally "honest" about light microscopy that other technologies just can't replicate.

What's Actually Going on Inside a Compound Microscope Light Microscope?

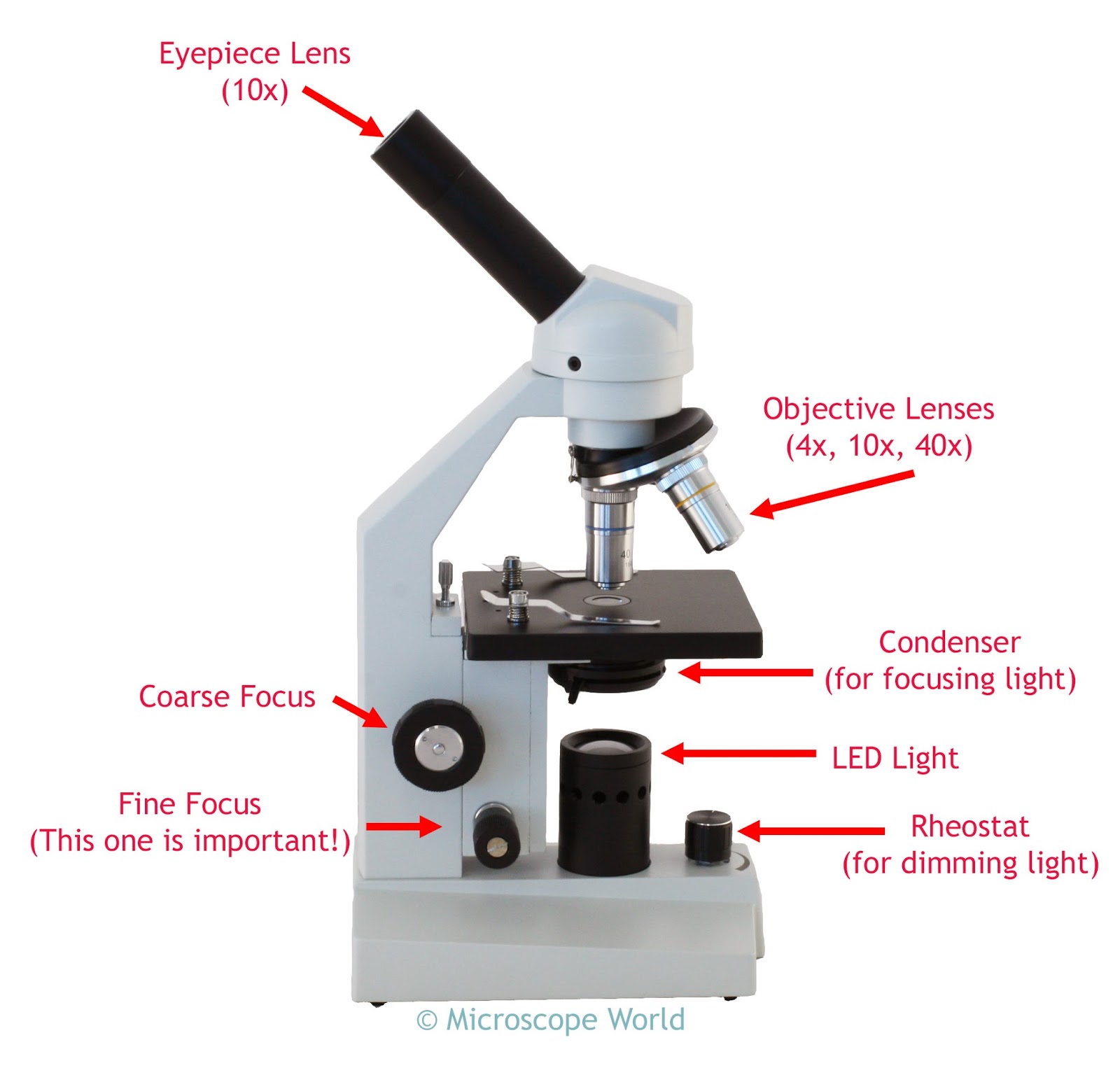

Basically, the "compound" part of the name is the secret sauce. You’ve got two lens systems working in tandem to pull off a visual heist. The first is the objective lens, sitting right above your slide. It does the heavy lifting, gathering light and creating a magnified image inside the tube. Then, the ocular lens (the eyepiece you actually look into) magnifies that internal image a second time.

It’s a relay race.

If your objective lens is 40x and your eyepiece is 10x, you’re looking at something 400 times larger than it actually is. It sounds simple, but the physics of light—specifically refraction—is doing some wild gymnastics to make that happen. When light passes through glass, it slows down and bends. By curving that glass perfectly, we can trick our eyes into seeing a tiny flea as if it were the size of a dinner plate.

One thing people often get wrong is thinking that more magnification always means a better image. Total myth. You can magnify a blurry image as much as you want, but it’ll still be a blurry image. The real MVP here is resolution. That is the ability of the microscope to distinguish between two points that are very close together. Without good resolution, high magnification is just "empty magnification." It’s like zooming in on a low-res photo on your phone; eventually, you just see big, useless blocks.

✨ Don't miss: Weather Radar in Edinburg TX: Why Your Phone Might Be Lying to You

The Components You Actually Need to Know

Forget the textbook diagrams for a second. Let's talk about what actually matters when you're sitting in front of one of these things.

The condenser is probably the most underrated part of the whole setup. Sitting under the stage, it doesn't magnify anything. Instead, it gathers the light from the bulb and focuses it into a tight, intense beam that hits your specimen. If your condenser is misaligned, your image will look grainy or washed out, no matter how expensive your lenses are. It’s the difference between a flashlight and a spotlight.

Then you have the diaphragm (or iris). You use this to control the "aperture" or the width of the light beam. You’d think more light is always better, right? Not really. If you’re looking at something nearly transparent, like a cheek cell, you actually want less light. Closing the diaphragm increases contrast, making those faint structures pop. It's a constant balancing act between brightness and detail.

A Note on "Oil Immersion"

When you get up to the 100x objective—the big boy—you usually have to use immersion oil. If you’ve ever tried to use a 100x lens without oil and wondered why everything looks like a muddy mess, this is why. At that high of a magnification, the light bends so sharply when it exits the glass slide and enters the air that it actually misses the lens entirely. The oil has the same refractive index as glass. It bridges the gap, "trapping" the light and funneling it straight into the lens. It's messy, but it's the only way to see bacteria clearly with light.

Why We Still Use Light Instead of Electrons

You might wonder why we don't just use Electron Microscopes (EM) for everything. I mean, EMs can see things thousands of times smaller than a compound microscope light microscope. But there's a catch. Or several.

📖 Related: The Only Example of a Polar Solvent You Actually Need to Understand

First off, EMs are huge, require a vacuum, and involve shooting a beam of electrons at a sample. This usually kills whatever you're looking at. You can't watch a live cell divide under an electron microscope. With a light microscope, you can literally watch the "dance" of life. You can see a paramecium hunting, or watch white blood cells chase down a bacterium in real-time.

Also, color.

Light microscopes show you the world in its natural hues (or the hues of the stains you apply). Electron microscopy is inherently black and white. Any color you see in those famous "National Geographic" shots of viruses is added later in Photoshop. For a pathologist trying to diagnose cancer, the specific way a cell takes up a pink or purple stain is a vital clue that you just don't get with electrons.

Common Blunders and How to Fix Them

I've spent years watching students and hobbyists struggle with these machines, and the same three problems pop up constantly.

- The "Eyelash" Problem: If you see a weird, hairy line across your view, it’s probably not a specimen. It’s your own eyelash. Move your eye slightly back or adjust the interpupillary distance (the space between the eyepieces).

- The Smash: This is the cardinal sin of microscopy. You're looking through the eyepiece, turning the coarse adjustment knob, and crunch—the lens hits the slide. Always start with the stage all the way up and move it down while looking through the lens, or watch the side of the microscope while you bring the lens close to the slide.

- Dirty Optics: People love to use their shirts to wipe lenses. Don't do that. You’ll scratch the coatings. Use lens paper and a tiny bit of specialized cleaner. Dust is the enemy of clarity.

The Reality of Modern Digital Integration

Technology has changed the game recently. We’re seeing a massive shift toward digital compound microscopes. Instead of squinting through an eyepiece, you’re looking at a 4K monitor.

Honestly, it’s better for your neck.

But it also allows for something called "image stacking." The microscope takes dozens of photos at slightly different focus levels and stitches them together. Since light microscopes have a very shallow depth of field (only a tiny slice of the object is in focus at once), stacking allows us to see a 3D-looking image where the whole object is crisp. It’s a hybrid approach that keeps the benefits of light but adds the power of modern computing.

Actionable Steps for Better Microscopy

If you’re looking to get into this, whether for work or as a hobby, here is how you actually get the best results:

- Master Köhler Illumination: This is a specific technique for aligning your light path. It sounds technical, but it’s basically just centering your light and focusing the condenser. It’s the single biggest jump you can make from "amateur" to "pro" results.

- Invest in Stains: Most biological things are clear. You won't see much without contrast. Grab some Methylene Blue (for animal cells) or Iodine (for plant cells). It’s like turning on the lights in a dark room.

- Start Low, Go Slow: Always start your search on the 4x objective. Find your "landmark," center it, and then move up. If you start at 40x, you’ll spend an hour looking at nothing but empty water.

- Check the Numerical Aperture (NA): When buying or using a lens, look for the NA number printed on the side (e.g., 0.65). The higher this number, the better the resolution. Don't just look at the magnification.

The compound microscope light microscope isn't going anywhere. It’s the bridge between our world and the invisible world. While it might seem like a relic of the 17th century, it remains the most vital tool for understanding biology in its living, breathing, colorful state. To get started today, grab a prepared slide kit or even a cheap digital eyepiece adapter for your existing scope; the ability to record and share what you see changes the experience from a solitary one to a collaborative exploration.