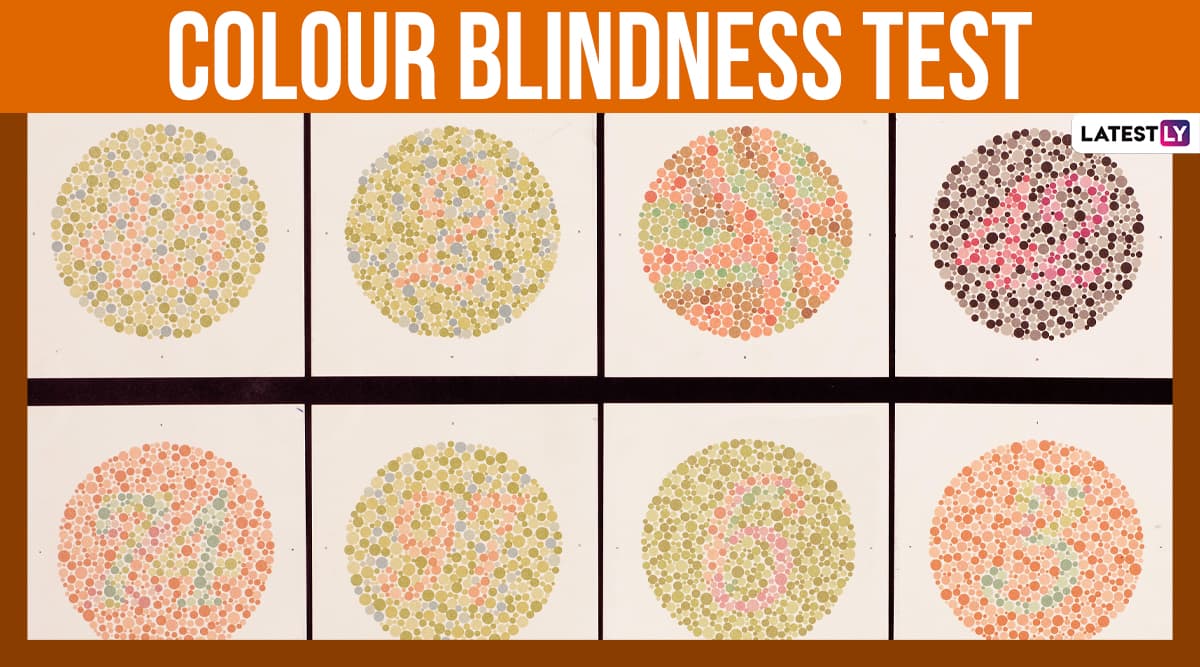

You’re staring at a circle of dots. Most of them are a muddy olive green, but there are a few stray specks of brownish-orange scattered in the middle. You squint. You tilt your laptop screen. Maybe you even rub your eyes, thinking there’s a smudge on your glasses. But the number—the one your friend insists is "so obvious"—just isn't appearing. Welcome to the world of the color blindness hard test. It’s frustrating. Honestly, it’s a bit humbling. But for about 300 million people worldwide, this isn't just a viral internet challenge; it’s a window into how their brain processes the visible spectrum.

Color vision deficiency (CVD) isn't usually about living in a black-and-white movie. That's a huge misconception. Most people who fail a "hard" version of these tests can see plenty of colors. They just can't see the difference between specific ones. When those colors are placed right next to each other in a chaotic pattern of dots, the "border" between the background and the hidden shape vanishes.

What Makes a Color Blindness Hard Test Actually "Hard"?

Most of us grew up seeing the standard Ishihara plates. You know the ones: a bright red "12" on a green background. Almost everyone can see that one because the contrast is dialed up to eleven. But a color blindness hard test plays a different game. It uses "transformation" and "vanishing" plates that rely on incredibly subtle shifts in saturation and hue.

Specifically, these tests target the "confusion lines" of the human eye. In the 19th century, a physicist named August Seebeck noticed that people with color blindness tended to confuse very specific sets of colors. Modern tests, like the Farnsworth-Munsell 100 Hue Test, take this to the extreme. Instead of just finding a number, you have to arrange caps in a perfect color gradient. If your "M" cones (green) or "L" cones (red) have an overlapping sensitivity, those caps will look identical. You’ll fail. And you’ll be confused why.

The difficulty usually stems from three things:

First, the luminosity. A well-designed hard test ensures the dots have the exact same brightness. If one dot is even slightly darker than another, a colorblind person can "cheat" by using light intensity to find the shape.

Second, the chroma. Hard tests use desaturated colors—think pastels, dusty greys, and muted teals.

Third, the "niche" deficiencies. While most people talk about red-green issues, the truly difficult tests look for Tritanopia (blue-yellow) or very mild cases of Anomalous Trichromacy.

The Science of the "Struggle"

Inside your retina, you’ve got these tiny photoreceptors called cones. Most people have three types. One reacts to long wavelengths (red), one to medium (green), and one to short (blue). In a "normal" eye, these three signals are distinct enough for the brain to triangulate almost any color.

But when you take a color blindness hard test, the test-maker is looking for "Protanomaly" or "Deuteranomaly." This is where your red or green cones haven't completely quit, but they’ve shifted their sensitivity. They’re leaning into each other's territory. It’s like trying to listen to two different radio stations that are broadcasting on almost the exact same frequency. You get static. In the context of the test, that static looks like a bunch of random dots with no hidden number.

💡 You might also like: Barras de proteina sin azucar: Lo que las etiquetas no te dicen y cómo elegirlas de verdad

The Ishihara vs. The Hard Stuff

We have to talk about Shinobu Ishihara. He was a Japanese ophthalmologist who published his first set of plates in 1917. Even over a century later, his work is the gold standard. However, the basic 14-plate or 24-plate sets you find in a school nurse’s office are "easy" by design. They want to catch the obvious cases.

A "hard" test often incorporates "Hidden Digit" plates. These are fascinating. They are designed so that a person with normal vision sees nothing, but a person with color blindness actually sees a number.

Wait, what?

It sounds like a magic trick. Basically, the test-maker uses colors that look different to a colorblind person because of how their specific "confusion" works, while the "normal" eye sees the dots as a uniform camouflage. If you see something your "normal-vision" friend doesn't, you might actually be the one with the deficiency.

Real-World Implications: It's Not Just About Dots

Why does any of this matter? Because life isn't made of Ishihara plates, but it is made of color-coded information.

Consider these scenarios:

- Electronics: That tiny LED on your charging brick that turns from orange to green.

- Cooking: Is the steak medium-rare, or is it still raw? To some, the pink of the meat blends perfectly with the grey of the seared outside.

- Charts: Think about a "hard" Excel spreadsheet where the "Projected Revenue" line is dark green and the "Actual Cost" line is dark brown.

- Weather Maps: Severe weather alerts often use a gradient from green to yellow to red. In a high-stakes situation, not being able to pass a color vision test can be a literal safety hazard.

Why You Might "Fail" a Test Online Even With Perfect Vision

Here is a dirty little secret about the color blindness hard test you find on a random website: your monitor is probably lying to you.

📖 Related: Cleveland clinic abu dhabi photos: Why This Hospital Looks More Like a Museum

Color calibration is a nightmare.

A professional ophthalmologist uses physical plates printed with specific inks that don't reflect light in a weird way. Your smartphone screen, on the other hand, uses a mix of Red, Green, and Blue (RGB) pixels. If your "Night Mode" is on, or if your "True Tone" setting is shifting the white balance to be warmer, the test is effectively broken. You might "fail" simply because your screen can't produce the exact wavelength required for the test to work.

Furthermore, glare is a huge factor. If you're taking a test under a bright fluorescent light, the reflections on your screen can wash out the subtle color differences. If you're serious about checking your vision, you need a controlled environment.

The Role of Genetics (And the Occasional Surprise)

Most color blindness is X-linked. This is why it hits men way harder—about 8% of men versus 0.5% of women. Since men only have one X chromosome, if that gene is faulty, there’s no backup. Women have two, so the healthy one usually does the heavy lifting.

But here is where it gets weird. Some women are "Tetrachromats." They actually have four types of cones. To them, a color blindness hard test isn't just easy; it’s laughably simple because they can see millions of color variations that the rest of us literally cannot imagine. They might see "shimmering" or "depth" in a plate that looks flat to everyone else.

On the flip side, you can "acquire" color blindness later in life. This isn't genetic. It can be caused by:

👉 See also: Baldwin Building Rochester Minnesota: What Most People Get Wrong

- Cataracts: They act like a yellow filter over your eye, muddying your blue-yellow perception.

- Medications: Certain drugs, like Plaquenil (used for arthritis/lupus) or even some antibiotics, can affect color vision.

- Aging: Honestly, our eyes just get less sensitive over time. The lenses yellow, and the cones lose some of their "snap."

Actionable Steps: What To Do If You Struggled With the Test

If you just took a "hard" test and the results were... discouraging, don't panic. But don't ignore it either.

1. Get a Professional Screening (The D-15 Test)

Skip the online quizzes for a moment. Ask an eye doctor for the Richmond HRR (Hardy-Rand-Rittler) test or the Farnsworth D-15. These are more sophisticated than the basic Ishihara. They can tell you exactly which part of the spectrum you're missing and how severe the gap is.

2. Adjust Your Digital Environment

If you find out you have a deficiency, use technology to your advantage. Windows, macOS, iOS, and Android all have "Color Filters" in their accessibility settings. You can toggle on a "Protanopia" or "Deuteranopia" filter that shifts the entire screen's palette into colors you can actually distinguish. It’s a game-changer for reading maps or playing video games.

3. Label Your World

Stop guessing. If you struggle with clothes, ask a friend to help you label your hangers (e.g., "Navy," "Black," "Dark Green"). If you're a hobbyist who paints or works with wires, buy a label maker. There is no shame in using a system to bypass a biological limitation.

4. Check Your Lighting

Sometimes, "failing" a color blindness hard test is just a symptom of poor lighting. Invest in "Full Spectrum" or "Daylight" LED bulbs (around 5000K to 6500K). These bulbs mimic natural sunlight and make it much easier to see the true hue of objects.

5. Explore Corrective Lenses

You've probably seen the viral videos of people putting on EnChroma glasses and crying. While they aren't a "cure" (they don't give you new cones), they do work by filtering out the specific wavelengths where your red and green cones overlap. This "widens" the gap between the signals, making colors pop in a way they didn't before. They don't work for everyone, but many people with mild-to-moderate deficiency find them transformative.

Ultimately, failing a color blindness test isn't about what's "wrong" with your eyes. It's about understanding that your "internal map" of the world is just drawn with a slightly different set of crayons. Once you know where the gaps are, you can stop squinting at the dots and start navigating the world with a lot more confidence.