Honestly, the first time you see the clearest picture of the sun, it’s a bit of a letdown. You expect a smooth, glowing ball of fire. Instead, you get what looks like a close-up of a caramel corn bucket or maybe some weirdly glowing cells under a microscope. It’s gritty. It’s textured. It’s violent.

That texture is actually the sun’s surface—the photosphere—boiling. We’re talking about cells the size of Texas constantly churning, rising, and sinking. This level of detail didn't happen by accident. It took the Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope (DKIST) in Hawaii to finally pierce through the atmospheric blur and show us what our star actually looks like when you stop squinting.

The Maui Giant That Changed Everything

For decades, we relied on space-based observatories like SOHO or the Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO). They were great because they didn't have to deal with Earth's annoying atmosphere. But they were small. If you want high resolution, you need a big mirror.

Enter the DKIST. Located on the summit of Haleakalā, this thing uses a 4-meter mirror. That is massive for a solar telescope. Most solar scopes are tiny because if you point a 4-meter mirror at the sun, you aren't just taking a picture; you're building a death ray. The heat generated at the focus is enough to melt metal in seconds. Engineers had to build a specialized cooling system that includes seven miles of piping and a nightly production of several tons of ice just to keep the equipment from vaporizing itself.

When they finally clicked the shutter, we got the clearest picture of the sun ever recorded. Those "popcorn" kernels are called granules. Each one is a column of plasma. The bright centers are where hot plasma is rising from the interior, and the dark lanes between them are where the cooled plasma is sinking back down. It’s a literal convection oven the size of a solar system.

🔗 Read more: Why Your 4 Digit Year of Birth is Becoming a Digital Security Nightmare

Why Resolution Matters for Our Power Grid

You might wonder why we spent hundreds of millions of dollars to look at solar popcorn. It’s not just for the desktop wallpapers.

The sun is basically a massive, messy magnetic engine. Everything we see—flares, coronal mass ejections (CMEs), sunspots—is driven by magnetic fields. But these fields are tangled and tiny at their source. To understand how a solar flare starts, you have to see the "roots."

Before DKIST, we could see the general neighborhood of a sunspot. Now, we can see the individual magnetic threads. It’s the difference between looking at a forest from a plane and standing next to a single tree to see the bark. This matters because when the sun has a "burp," it sends a wave of charged particles toward Earth. If it’s big enough, it fries satellites and knocks out power grids.

- The 1859 Carrington Event: If that happened today, we’d be in the dark for months.

- The 1989 Quebec Blackout: A solar storm took out the grid in seconds.

By getting the clearest picture of the sun, scientists like Dr. Thomas Rimmele (the director of the DKIST project) can start predicting "space weather" with the same accuracy we use for hurricanes. We’re trying to move from a 48-minute warning to a 48-hour warning.

The Tiny Details in the Dark Lanes

If you look really closely at those high-res images—the ones that look like cracked desert earth—you’ll see tiny, bright spots in the dark channels. These are the "magnetic bright points."

They are essentially windows into the deeper layers of the sun. These points are where magnetic flux is concentrated. Think of them like the exhaust valves of a car engine. They channel energy into the outer atmosphere, the corona.

This leads us to the biggest mystery in solar physics: Why is the sun’s surface roughly 6,000 degrees Celsius, but the atmosphere above it is over a million degrees? It defies common sense. It’s like walking away from a campfire and getting hotter the further you go.

The clearest picture of the sun provides the data to solve this. We can now see the "magnetic switchbacks" and waves that transport that heat. It turns out the sun's surface is vibrating and snapping like a whip, flinging energy upward.

Is it Just Hawaii?

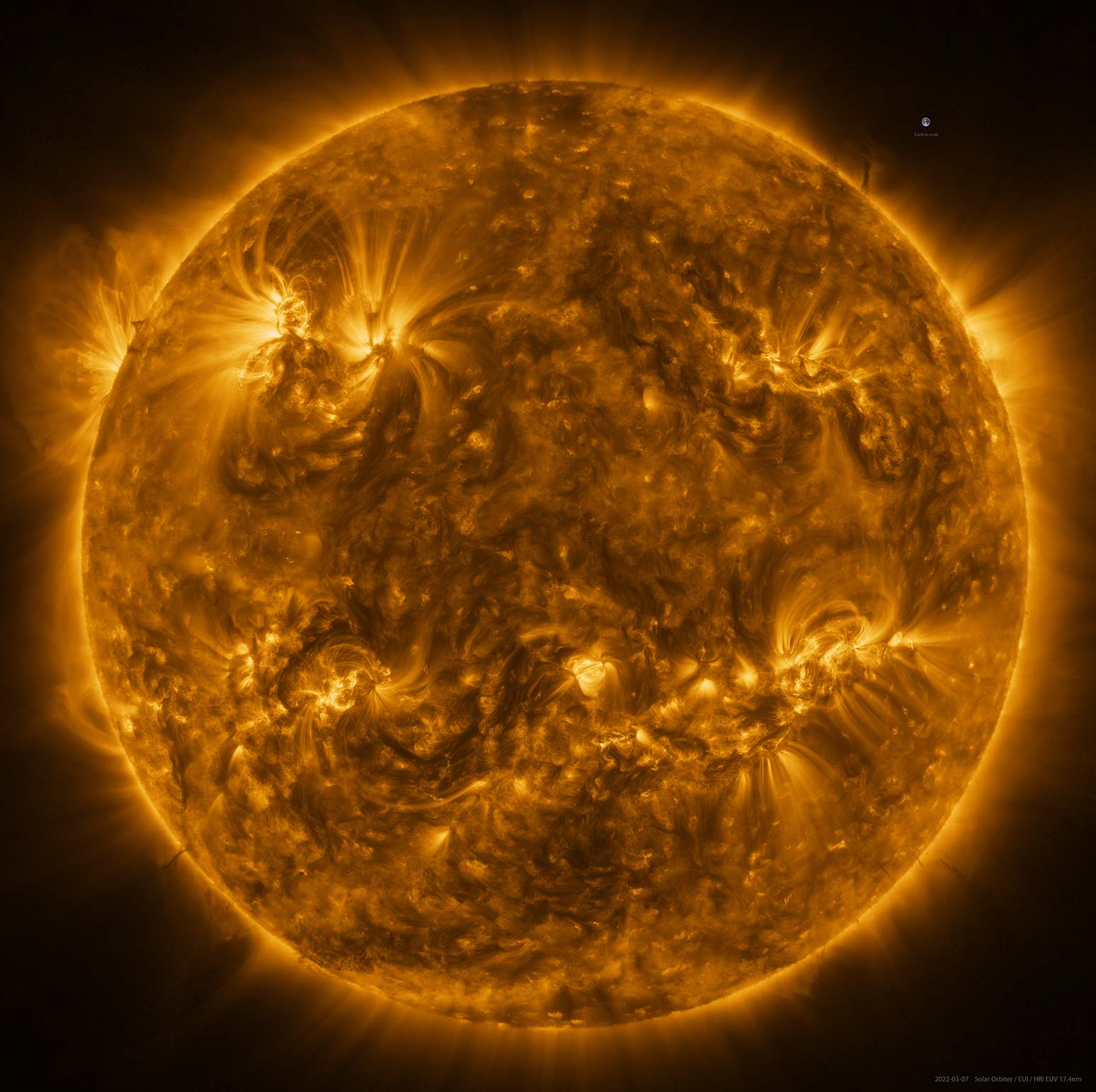

While DKIST is the heavyweight champion, it isn't the only player. The European Space Agency’s Solar Orbiter (SolO) is currently screaming through the inner solar system. It’s getting closer than any camera-carrying craft has ever been.

In 2022, SolO captured a full-disc image of the sun that was composed of 25 individual shots tiled together. The result was a 83-megapixel image. It’s stunning. But it serves a different purpose than the ground-based DKIST. While the Hawaii telescope gives us the microscopic view of the "popcorn," the Solar Orbiter gives us the "global" view.

Then there's the Parker Solar Probe. It doesn't actually have a camera pointed directly at the sun because it’s too busy trying not to melt. It’s literally "touching" the sun, flying through the corona. It measures the wind and the dust, providing the "feel" to go along with the "sight" provided by the clearest picture of the sun.

How You Can See It Yourself

You don't need a billion-dollar budget to see the sun’s texture, though you won't get the DKIST "popcorn" from your backyard.

👉 See also: How Do You Make Facebook Friends List Private Without Breaking Your Profile

Most people think they can just point a telescope at the sun. Don't do that. You will go blind instantly. Permanent damage. Instead, hobbyists use Hydrogen-alpha (H-alpha) filters. These filters block out almost all light except for a very specific red wavelength.

When you look through an H-alpha scope, the sun isn't a white or yellow ball. It’s a deep, textured crimson. You can see prominences—huge loops of plasma—leaping off the edge. You can see "filaments" which are just prominences seen against the bright face of the sun.

The Limits of Our Vision

Even with the clearest picture of the sun, we are still struggling with "seeing." Earth's atmosphere is like looking through a swimming pool. The air ripples. That’s why DKIST uses "adaptive optics."

It’s a mirror that deforms itself 2,000 times per second to cancel out the atmospheric shimmer. It’s basically noise-canceling headphones, but for light.

Even then, we’re only seeing the surface. The interior of the sun is opaque. We have to use helioseismology—basically measuring "sunquakes"—to figure out what’s happening inside. It’s like trying to figure out what’s inside a Christmas present by shaking it and listening to the rattle.

The Future of Solar Photography

We aren't done. The next step is a multi-messenger approach. We want to sync up the clearest picture of the sun with real-time data from the Parker Solar Probe and the Solar Orbiter.

Imagine seeing a magnetic thread snap in Hawaii, then seeing the Solar Orbiter catch the resulting flare from the side, while the Parker Probe flies through the actual cloud of particles a few hours later. That’s the "holy grail" of solar physics.

We’re living in a golden age of astronomy that nobody is really talking about. Everyone loves James Webb and its distant galaxies, but the sun is the only star we can see in high definition. It’s our laboratory. Everything we learn about the sun applies to the billions of other stars in the universe.

Putting the Data to Work

If you’re interested in tracking this yourself, you don't have to wait for a press release. The data from these telescopes is often public.

- Check SpaceWeather.com: This is the daily "weather report" for the sun. It tracks sunspots and incoming flares.

- Visit the NSO (National Solar Observatory) Gallery: They host the raw and processed images from the DKIST. You can download the clearest picture of the sun in its full, multi-gigabyte glory.

- Use the JHelioviewer: This is a free tool that lets you browse through images from multiple solar observatories. You can create your own time-lapse movies of solar flares.

- Follow the Solar Cycle: The sun goes through an 11-year cycle. We are currently approaching "Solar Maximum." This means more spots, more flares, and more opportunities for record-breaking photos.

The sun isn't a static object. It’s a living, breathing, magnetic beast. The more we look at it, the more we realize how little we actually know. Every time we get a clearer picture, we find ten more things we can't explain. And honestly, that's the best part.