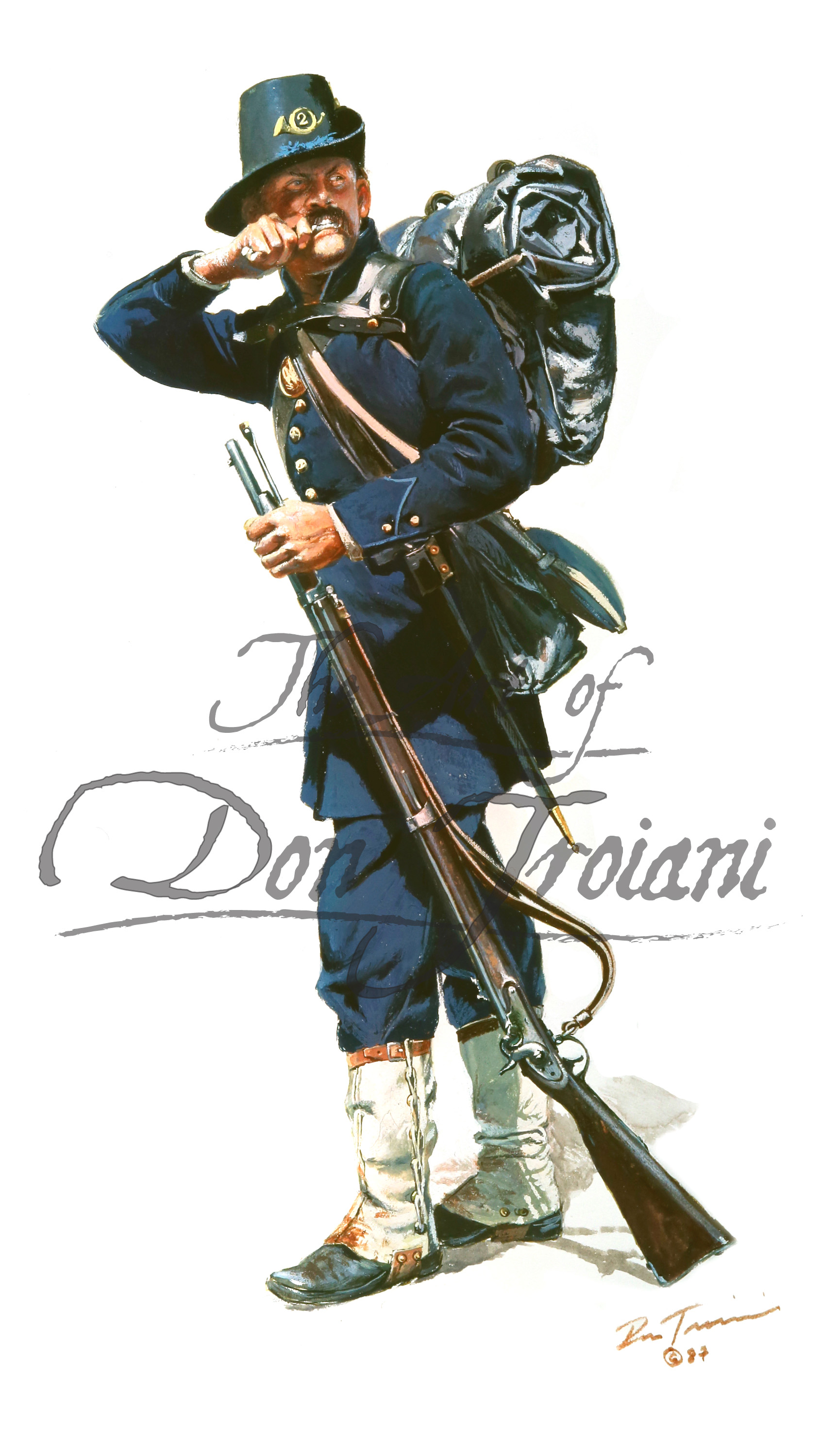

Black hats. That’s usually the first thing people notice in the old tintypes. While the rest of the Union Army was trudging through the mud in standard-issue forage caps—those floppy, blue things that looked like oversized baseball hats—these guys from the Midwest were rocking tall, stiff, black felt Hardee hats. It was a choice. A statement. They looked like giants, and frankly, they fought like they were invincible.

If you’ve ever gone down the rabbit hole of Union Army history, you eventually hit a wall of statistics that all point to one group: the civil war iron brigade. They weren't just "good" soldiers. They were statistical anomalies. Originally composed of the 2nd, 6th, and 7th Wisconsin, and the 19th Indiana, they were later joined by the 24th Michigan. They were the only all-Western brigade in the Eastern Theater for a long time. These were guys who grew up clearing timber and wrestling plows in the "Old Northwest," and they brought a certain kind of rugged, frontier violence to the sophisticated slaughter of the Virginia campaigns.

It’s easy to get lost in the mythology. But the reality? The reality was much bloodier.

The Myth of the Black Hats

They weren't born the "Iron Brigade." In the early days of 1861, they were just a bunch of farm boys and immigrants—lots of Germans and Norwegians—who didn't know how to salute properly. Their first commander, Rufus King, was a literal newspaper editor. But then came John Gibbon. Gibbon was a West Point guy, a regular army stickler who hated the "volunteer" look. He's the one who forced them into those ridiculous black hats and white leggings. The men hated him for it. They called him a tyrant.

But then came Brawner’s Farm.

It was August 28, 1862. The sun was going down near Groveton, Virginia. The brigade stumbled right into Stonewall Jackson’s division. We’re talking about a stand-up, face-to-face musketry duel at less than a hundred yards. No cover. No trenches. Just two lines of men standing in a field shooting each other in the face for over an hour. It was some of the most concentrated killing of the entire war. Jackson’s men, seasoned veterans, were stunned. They expected these "Westerners" to break. They didn't.

That night, the legend started. It’s said that during the battle of South Mountain, General George McClellan saw them pushing up the National Road against heavy fire and remarked that they must be made of iron. Whether he actually said those exact words is debated by some historians, but the name stuck. The civil war iron brigade had arrived, and the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia learned to look for the black hats. If you saw those hats, you knew you were in for a long, terrible day.

🔗 Read more: Finding Another Word for Calamity: Why Precision Matters When Everything Goes Wrong

Why the Midwest Produced Different Soldiers

There’s this weird geographical tension in 1860s America. The Easterners in the Army of the Potomac often looked down on the Westerners as unrefined. But that lack of "refinement" translated into a terrifying durability.

The 24th Michigan joined the brigade later, and they had a chip on their shoulder. They had to prove they belonged with the "Old Brigade." At Gettysburg, they proved it so hard they basically ceased to exist as a functioning unit.

Think about the physical reality of these men. Most were over six feet tall in an era where the average height was much lower. They were healthy. They were used to physical labor that would break a modern person. When they marched, they covered ground faster than almost any other unit. But more than that, they had a weirdly tight bond. Because they were all from the same region, they weren't just fighting for "The Union." They were fighting for their neighbors. If you ran, everyone back in Madison or Indianapolis would know by the next mail delivery.

Gettysburg: The Day the Iron Broke

If you go to McPherson’s Ridge in Gettysburg today, it’s peaceful. In July 1863, it was a slaughterhouse. This was the civil war iron brigade’s finest and most tragic hour. They were the first infantry on the scene to support John Buford’s cavalry.

They smashed into Archer’s Tennessee brigade in Herbst’s Woods. They even captured General James J. Archer himself—the first time a general in Lee’s army had been captured since Lee took command. But the cost? It was unsustainable.

The 26th North Carolina was across from them. Two of the most tenacious units of the war just ground each other into dust. By the time the Iron Brigade retreated through the town of Gettysburg to Cemetery Hill, the 24th Michigan had lost 363 out of 496 men. Read that again. That’s an 80% casualty rate. The 2nd Wisconsin went in with 302 men and came out with 69.

💡 You might also like: False eyelashes before and after: Why your DIY sets never look like the professional photos

They saved the Union position on the first day. They bought the time the rest of the army needed to take the high ground. But the "Iron" was effectively shattered. While the brigade continued to serve through the end of the war, including at the Siege of Petersburg, it was never the same. They had to be reinforced with other units from different states, and the unique "Western" identity started to blur.

Common Misconceptions About the Brigade

People think they were always successful. Honestly, they weren't. They took massive losses because their style of fighting was essentially "refuse to move." That’s brave, but in the age of the rifled musket, it’s also a recipe for extinction.

Another big mistake people make is thinking the Hardee hat was a "special" uniform just for them. It wasn't. It was the official dress hat of the US Army. Most units just threw them away because they were heavy and hot. The Iron Brigade kept them out of spite and pride. They turned a piece of unwanted military gear into a psychological weapon.

And let's talk about the "Western" thing. People often forget that by 1863, the 24th Michigan was arguably the heart of the unit. Even though they were the "new guys," their performance at Gettysburg is what most military historians point to when they talk about the brigade's peak.

How to Experience the History Yourself

If you’re a history buff, you can’t just read about this stuff. You have to see it.

Start at Gettysburg. Stand in the woods near the Willoughby Run. You can see the monuments for the 24th Michigan and the 2nd Wisconsin. It’s haunting. There’s a specific energy there. You can see exactly how close the lines were. You realize that at that distance, you aren't aiming at "the enemy." You are looking into another man's eyes.

📖 Related: Exactly What Month is Ramadan 2025 and Why the Dates Shift

For those closer to the Midwest, the Wisconsin Veterans Museum in Madison is a gold mine. They have actual artifacts, including some of those famous black hats. Seeing the size of the hats helps you realize how much these men stood out on a smoky battlefield.

Insights for the Modern History Enthusiast

The civil war iron brigade teaches us something about "brand identity" before that was even a corporate term. They leaned into their reputation. They knew the Confederates feared them, so they made sure they were visible. It was a form of psychological warfare.

But it also reminds us of the cost of being "the best." The units that get the toughest jobs are the ones that disappear the fastest. The Iron Brigade has the highest percentage of deaths in battle of any brigade in the Federal armies. That’s a heavy legacy. It’s not just about glory; it’s about a generation of Midwestern men who simply never came home.

To truly understand this unit, look past the "iron" nickname. Look at the letters they wrote. They were scared. They were tired. They were often sick with dysentery. But when the order came to move, they put on those ridiculous black hats and walked into the fire.

Moving Forward With Your Research

If you're looking to dive deeper into the gritty details of the Western regiments, stop looking at general overviews. The real gold is in the regimental histories.

- Find the Regimental Histories: Look for "The 24th Michigan of the Iron Brigade" by O.B. Curtis. It was written by a man who was actually there. It’s messy, biased, and absolutely fascinating.

- Visit the National Archives: If you really want to go deep, search the Compiled Military Service Records (CMSR). You can see the individual enlistment papers for the men of the 6th or 7th Wisconsin. Seeing a shaky "X" where a man signed his name makes the history feel real in a way a textbook never will.

- Compare Casualty Stats: Look at Fox’s "Regimental Losses in the American Civil War." It’s a dry book of numbers, but when you see the Iron Brigade units consistently at the top of the list, the "Iron" nickname starts to feel a lot more tragic than heroic.

- Trace the Geography: Use Google Earth to map out the movements from Brawner’s Farm to Antietam’s Cornfield to Gettysburg. You’ll see the sheer mileage these men covered on foot, mostly in wool uniforms, while carrying 40 pounds of gear.

The story of the Iron Brigade isn't a story of easy victory. It's a story of endurance. It's about what happens when "regular" people are asked to do the impossible, and they decide, for better or worse, not to take a single step back.