Ever wonder why you suddenly start seeing those "Keep It Real" commercials right around the time the temperature drops? It isn't just a coincidence or some collective seasonal fever. It's actually the result of a very specific, very legal, and honestly pretty fascinating group called the Christmas Tree Promotion Board. Most people have never heard of them. They operate in the background of the agricultural world, making sure that when you go to buy a tree, you’re looking at a Douglas Fir or a Fraser Fir instead of a box from a big-box retailer containing a plastic replica made overseas.

It’s kind of a wild concept when you think about it.

The Christmas Tree Promotion Board (CTPB) is what’s known as a "checkoff program." If you’ve heard of "Got Milk?" or "Beef: It’s What’s For Dinner," you already know how this works. Basically, the industry taxes itself to pay for marketing. It isn't a government agency funded by your tax dollars, even though it was established under the authority of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Instead, it’s funded by the farmers themselves. Specifically, growers who produce more than 5,000 trees annually pay a small fee per tree—currently 15 cents—into a collective pot.

That pocket change adds up fast.

The Fight for the American Living Room

The real reason the Christmas Tree Promotion Board exists is a bit of a survival story. Back in the 1960s and 70s, real trees owned the market. There wasn't really a choice. But then, the artificial tree industry started getting really good at what they do. They started selling "convenience." No needles to vacuum. No watering. No fire hazards (or at least, fewer perceived ones). By the early 2000s, the real tree industry was in a tailspin. Market share was plummeting.

The industry realized they couldn't fight back as individual small farms. A family farm in Oregon doesn't have the budget to run a national ad campaign. But 3,000 farms? Together, they have a voice.

The CTPB was officially kicked off in 2015 after years of internal debate within the industry. Some farmers hated the idea. They didn't want the government involved in their business, even if it was just to oversee the fund. Others saw it as the only way to keep their kids' inheritance—the farm—from being turned into a subdivision. Honestly, it was a messy start. There was even a brief "Christmas tree tax" controversy that blew up in the media, which was mostly a misunderstanding of how the funding worked. But once the dust settled, the board got to work.

👉 See also: E-commerce Meaning: It Is Way More Than Just Buying Stuff on Amazon

How the Money Actually Gets Spent

You might think they just buy billboards. They do, but it’s way more data-driven than that. They track "sentiment." They want to know why a 28-year-old in a city apartment chooses a fake tree over a real one. Usually, the answer is "I don't want to deal with the mess."

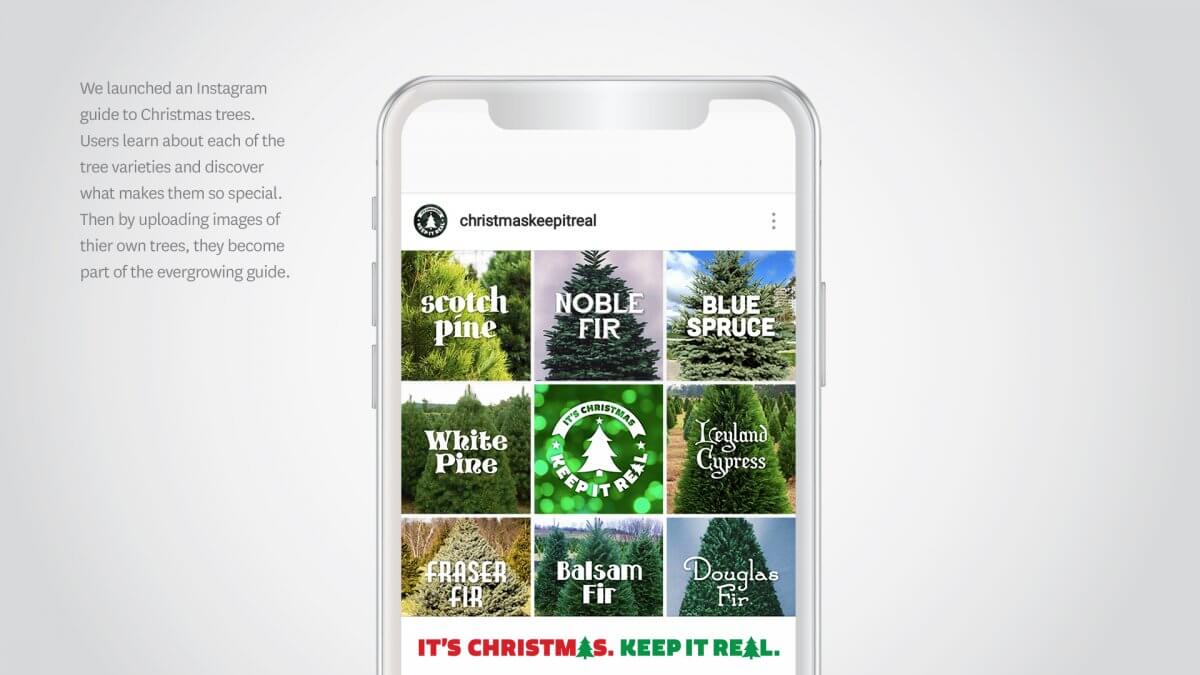

So, the Christmas Tree Promotion Board creates content that tackles that head-on. They partner with influencers. They run digital ads targeting people who just moved into new homes. They focus heavily on the "experience"—the smell, the trip to the farm, the tradition. They’ve basically rebranded the "mess" of needles as a hallmark of authenticity. It’s brilliant marketing.

- Research: They fund studies on how to keep trees fresher longer.

- Education: They provide retailers with kits on how to care for the inventory so the trees don't look dead by December 10th.

- Media Relations: When a news outlet runs a story about "real trees causing fires," the CTPB is the group that calls them up with actual data to provide context.

The Environmental Argument You Didn't Expect

One of the biggest wins for the Christmas Tree Promotion Board has been leaning into the "green" aspect of real trees. For a long time, people thought cutting down a tree was bad for the environment. It feels counterintuitive to cut something down to be "eco-friendly."

But the CTPB hammered home a different reality. Real trees are a crop, just like corn or wheat. For every tree cut down, farmers usually plant one to three more. While those trees are growing (which takes about 6 to 10 years), they’re absorbing carbon dioxide and providing a habitat for wildlife. Meanwhile, most artificial trees are made of PVC and lead in factories overseas and eventually sit in a landfill for a thousand years.

By framing the real tree as the "sustainable" choice, the board tapped into the values of younger generations. It changed the conversation from "real vs. fake" to "natural vs. plastic."

It’s Not Just About Ads

The board is made up of actual growers. People like Beth Walterscheidt or Derek Ahl. These are folks who spend their summers shearing trees in the heat so they grow in that perfect cone shape. When they sit in a board meeting, they aren't just looking at spreadsheets; they’re looking at the future of their livelihood.

✨ Don't miss: Shangri-La Asia Interim Report 2024 PDF: What Most People Get Wrong

They oversee a budget that usually hovers around $2 million to $3 million a year. In the world of national advertising, that’s actually a tiny amount. To put it in perspective, a single 30-second Super Bowl ad costs more than double their entire annual budget. This forces them to be incredibly scrappy. They can't outspend the big retailers, so they have to outsmart them with viral social media campaigns and grassroots PR.

Why This Matters to You (Even If You Don't Care About Farming)

The Christmas Tree Promotion Board is a case study in how a legacy industry survives in a modern world. It’s about the tension between convenience and tradition.

If they fail, the real tree industry likely shrinks into a niche, luxury product. Prices go up because supply drops as farms close. The "cut-your-own" farm experience, which is a staple of American winter culture, starts to disappear. By stabilizing the demand, the CTPB helps keep these farms viable.

There's also the economic ripple effect. Real trees are a $1 billion+ industry in the U.S. That money stays largely in rural communities. Oregon, North Carolina, Michigan, and Pennsylvania are the heavy hitters. When you buy a real tree, you're essentially supporting a domestic supply chain that involves truck drivers, seasonal laborers, and local retail lots.

Common Misconceptions About the Board

People often get two things wrong. First, they think it’s a government subsidy. It isn't. Not a cent of the marketing budget comes from the federal treasury. The USDA just provides the legal framework to make sure everyone pays their fair share and the money isn't embezzled.

Second, people think the board sets the prices of trees. They don't. Supply and demand do that. If there’s a shortage—like the one we saw a few years ago caused by the 2008 financial crisis (farmers planted fewer trees then, which hit the market a decade later)—the CTPB can’t do much about the price. They just try to make sure you still want the tree even if it costs ten dollars more than it did last year.

🔗 Read more: Private Credit News Today: Why the Golden Age is Getting a Reality Check

What Most People Get Wrong About "Real" Trees

There is this persistent myth that real trees are a major cause of house fires. The Christmas Tree Promotion Board spends a lot of time fighting this. Statistically, Christmas tree fires are incredibly rare. According to the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA), they account for a tiny fraction of one percent of all home fires. Most of those happen because of faulty wiring or candles, not the tree itself spontaneously combusting.

The board’s "Real Trees" campaign emphasizes hydration. If you keep the tree watered, it’s almost impossible to ignite with a standard spark. They've shifted the narrative from "trees are dangerous" to "just water your tree, it's fine."

The Logistic Nightmare of the Holidays

Imagine trying to coordinate the harvest and shipment of 25 to 30 million living things in a three-week window. That’s what the industry deals with every year. The CTPB helps by providing data to growers about where the demand is shifting. If people in Texas are suddenly obsessed with Nordmann Firs, the board's research helps growers in the Pacific Northwest prepare for that shift years in advance.

It's a slow-motion business. You can't just "print" more trees if you have a good sales year. You have to wait eight years for the next batch to grow. That makes the board’s job of "demand leveling" vital. They need to keep interest steady so growers don't overplant or underplant.

Actionable Steps for the Conscious Consumer

If you want to support the industry and make the most of what the Christmas Tree Promotion Board is trying to preserve, here is how you actually do it without getting overwhelmed by the marketing.

- Check the trunk: When buying from a lot, ask for a fresh cut (about half an inch off the bottom). If the tree was cut weeks ago, the sap has sealed the bottom, and it won't drink water.

- The "Bounce" Test: Pick up the tree and bounce the stump on the ground. A few brown needles falling off is normal. A rain of green needles means the tree is already toast.

- Recycle, don't trash: Almost every city has a "Treecycle" program where they turn old trees into mulch or use them for erosion control in coastal areas. This completes the "green" cycle the CTPB talks about.

- Support Local: If you can, go to a choose-and-cut farm. It cuts out the middleman and ensures the farmer gets the maximum profit, which keeps that land from being paved over.

The Christmas Tree Promotion Board might seem like just another bureaucratic entity, but it’s really the heartbeat of a very old-school industry trying to stay relevant in a high-tech world. They are the reason that, despite the convenience of a box in the attic, millions of people still choose to drag a heavy, sap-covered, needle-dropping piece of nature into their homes every December. It’s a victory of sentiment over logic, and in the world of business, that’s the hardest win of all.