Walk into the nave of Chartres Cathedral on a sunny afternoon and you’ll see people doing something weird. They aren't looking at the altar. They’re staring at the floor. They are watching "the light." Specifically, they're waiting for a beam of sunlight to pass through a tiny hole in a stained-glass pane and hit a specific white stone on the floor. It’s a precision astronomical event staged in 12th-century glass. But the real show is higher up. The Chartres Cathedral rose window isn't just a pretty circle of glass; it’s a high-tech survival of a lost way of seeing the world.

Honestly, calling it "art" feels like an understatement. It’s more like a hard drive.

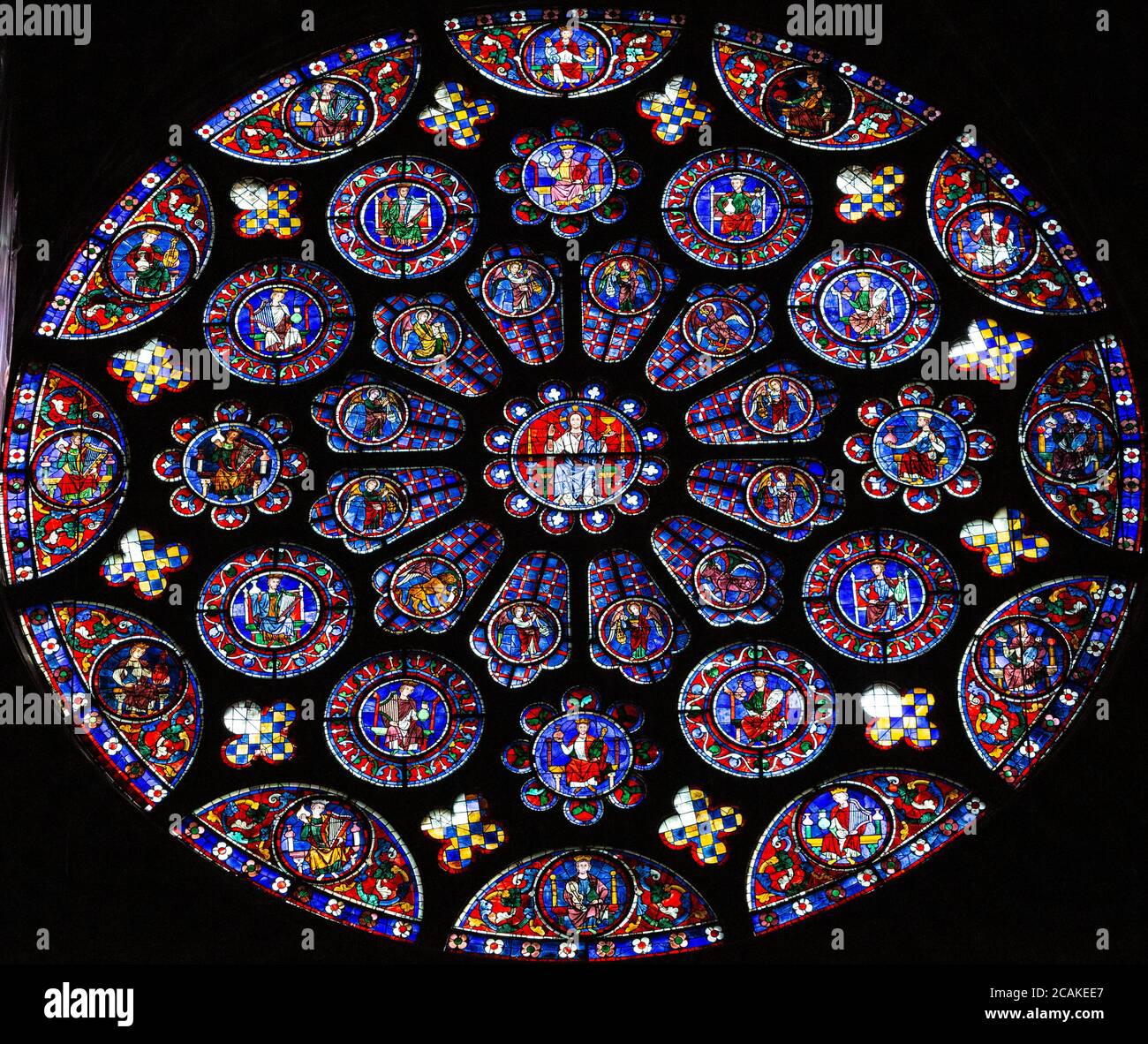

Most people visit Chartres on a day trip from Paris, snap a photo of the West Rose, and leave. They miss the point. They see colors—cobalt, ruby, emerald—but they don't see the math. The builders of Chartres were obsessed with "Divine Proportion." They believed that because God created the universe using number and weight, they could bridge the gap between Earth and Heaven by building with those same numbers. When you look at the North Rose, you aren't just looking at Mary and the prophets. You’re looking at a geometry lesson that was meant to keep your soul from drifting away.

The blue that nobody can quite copy

If you’ve spent any time reading about medieval art, you’ve heard of "Chartres Blue." It’s a specific, luminous shade of cobalt that seems to glow even when there’s almost no light outside. It’s legendary. During the World Wars, the local townspeople were so terrified of losing the glass that they painstakingly removed every single panel and hid them in the countryside. Every. Single. One.

Why the obsession? Because the recipe for that blue was effectively lost for centuries.

Medieval glassmakers didn't have a Pantone swathe. They used metal oxides. To get that specific Chartres Blue (bleu de Chartres), they used a soda-based glass colored with cobalt imported from the Lahn Valley in Germany. It’s chemically different from the potash-based glass used in later centuries. It has a higher refractive index. Basically, it catches the light and bounces it around inside the glass before letting it hit your eye. It’s bright. Even on a grey, rainy Northern French day, the windows look like they’re plugged into a battery.

Louis IX—Saint Louis himself—donated the North Rose. You can see his royal lilies (the fleurs-de-lis) at the bottom. He wasn't just being a generous donor; he was marking his territory. He wanted his lineage baked into the very light of the cathedral.

Geometry is the hidden language

Look at the structure. It’s a circle, obviously. But it’s a circle built on the number twelve.

Twelve apostles. Twelve tribes of Israel. Twelve signs of the zodiac. Twelve months in a year. For the medieval mind, twelve was the number of the "universal." It represented the intersection of the spiritual (the number three) and the material (the number four). 3 x 4 = 12.

The West Rose, which is the oldest of the three big ones, dates back to around 1215. It depicts the Last Judgment. In the center sits Christ. Radiating out from him are the circles of the chosen and the damned. It’s supposed to be overwhelming. Imagine being a 13th-century peasant. You live in a hut made of mud and straw. You see mostly brown, grey, and green your whole life. Then you walk into this stone cavern and see a 40-foot-wide explosion of pure, saturated color.

It would have felt like looking at a different dimension.

🔗 Read more: Omaha Nebraska to Salt Lake City Utah: The Reality of the 950-Mile Westward Push

What the North Rose tells us about power

The North Rose is my personal favorite because it’s so incredibly moody. It’s dedicated to the Virgin Mary, which makes sense because Chartres' big claim to fame is the Sancta Camisia—the tunic Mary supposedly wore when she gave birth to Jesus.

But look closer at the figures surrounding the central medallion. You’ve got kings of the Old Testament. David, Solomon, Rehoboam. They aren't just there for Sunday school vibes. They are there to legitimize the French monarchy. By placing the ancestors of Christ in the window, the designers were telling the public that the current King of France was part of that same holy lineage. It’s political propaganda disguised as theology.

And then there's the "Black Virgin."

There is a lot of scholarly debate about why the central figure of Mary in the North Rose (and the famous statue in the crypt) is so dark. Some say it's just the aging of the lead and the glass. Others, like historian Jean Markale, suggest it taps into much older, pre-Christian traditions of the "Earth Mother." Whatever the "truth," the effect is hypnotic. The deep reds and purples of the North Rose create a cool, contemplative atmosphere that contrasts sharply with the fiery, sun-drenched South Rose.

The South Rose: A different kind of energy

The South Rose is the "New Testament" window. It’s focused on Christ in Glory. If the North is about lineage and the past, the South is about the future and the triumph of the soul.

What’s wild is how these windows interact with the sun. Because the Earth tilts, the sun hits the South Rose directly during the day, flooding the church with warm light. The North Rose, facing the colder part of the sky, stays mysterious and blue. The architects knew this. They designed the glass density to account for the intensity of the sun on each side of the building.

It’s an analog computer.

- The West Rose: Focuses on the end of time (Last Judgment).

- The North Rose: Focuses on the Incarnation and the past (Old Testament).

- The South Rose: Focuses on the eternal reign of Christ.

The 2017 restoration controversy

You can't talk about the Chartres Cathedral rose window today without mentioning the "cleaning."

A few years ago, the French government finished a massive restoration of the cathedral interior. They didn't just clean the windows; they painted the soot-covered stone walls a creamy white with fake "masonry lines" painted on top. People lost their minds. Critics like Martin Filler called it a "cultural disaster."

The argument was that the dark, atmospheric "Gothic" look we’ve loved for centuries was actually just 800 years of dirt and candle smoke. The restorers claimed they were bringing the cathedral back to its original 13th-century appearance.

The effect on the windows was radical.

When the walls were dark, the windows were the only source of light. They popped like neon signs. Now that the walls are light, the contrast is lower. Some say the windows have lost their "punch." Others argue that for the first time in centuries, we can actually see the details of the glass because our eyes don't have to struggle with the extreme shadows of the nave.

It’s a trade-off. Do you want the "authentic" bright 1200s experience, or the "romantic" dark 1800s experience? There’s no right answer.

📖 Related: Nashville Weather by Month: What Most People Get Wrong

How to actually "read" the glass

Most tourists walk through in twenty minutes. Don't do that. If you want to actually see the Chartres Cathedral rose window, you need binoculars. Seriously. Bring a pair of bird-watching binoculars.

Without them, the windows are just patterns. With them, you see the tiny details: the expressions on the faces of the prophets, the specific tools held by the "tradesmen" who funded the windows (like the bakers and the furriers), and the intricate floral borders.

- Start at the bottom: Medieval windows are usually read from bottom to top, left to right, like a comic book.

- Look for the "donors": Usually in the bottom corners. You’ll see vine-dressers or stone-cutters. It was their way of saying "we paid for this."

- Watch the floor: If you’re there around noon on the summer solstice, look for the "St. John’s Light" hitting that specific stone I mentioned earlier.

- Ignore the crowds: Sit in a chair, put your head back, and just let your eyes adjust for ten minutes. The colors change as your pupils dilate.

The glass isn't just a window. It’s a filter for reality. The people who built Chartres didn't think of "light" as just physics. They thought of it as lux nova—the new light of the divine. They wanted to transform the harsh, biting sun of the French countryside into something soft, colored, and holy.

What to do next

If you're planning a trip or just obsessed with Gothic architecture, don't just look at photos. The scale is impossible to capture on a screen.

- Check the weather: Go on a day with "intermittent clouds." The way the windows "turn on and off" as clouds pass over the sun is a religious experience even if you aren't religious.

- Read Malcolm Miller: He is the legendary guide who has spent over 60 years deciphering these windows. His books are the gold standard for understanding the "literacy" of the glass.

- Visit the "Centre International du Vitrail": It’s just a few steps from the cathedral. They show you how the glass is actually made, which makes you realize how insane it was to build these things in the 1200s.

Go to Chartres. Stand under the West Rose. Forget your phone for a second. Just look up and realize that 800 years ago, someone figured out how to turn a stone wall into a kaleidoscope. That’s a kind of magic we still haven't quite topped.