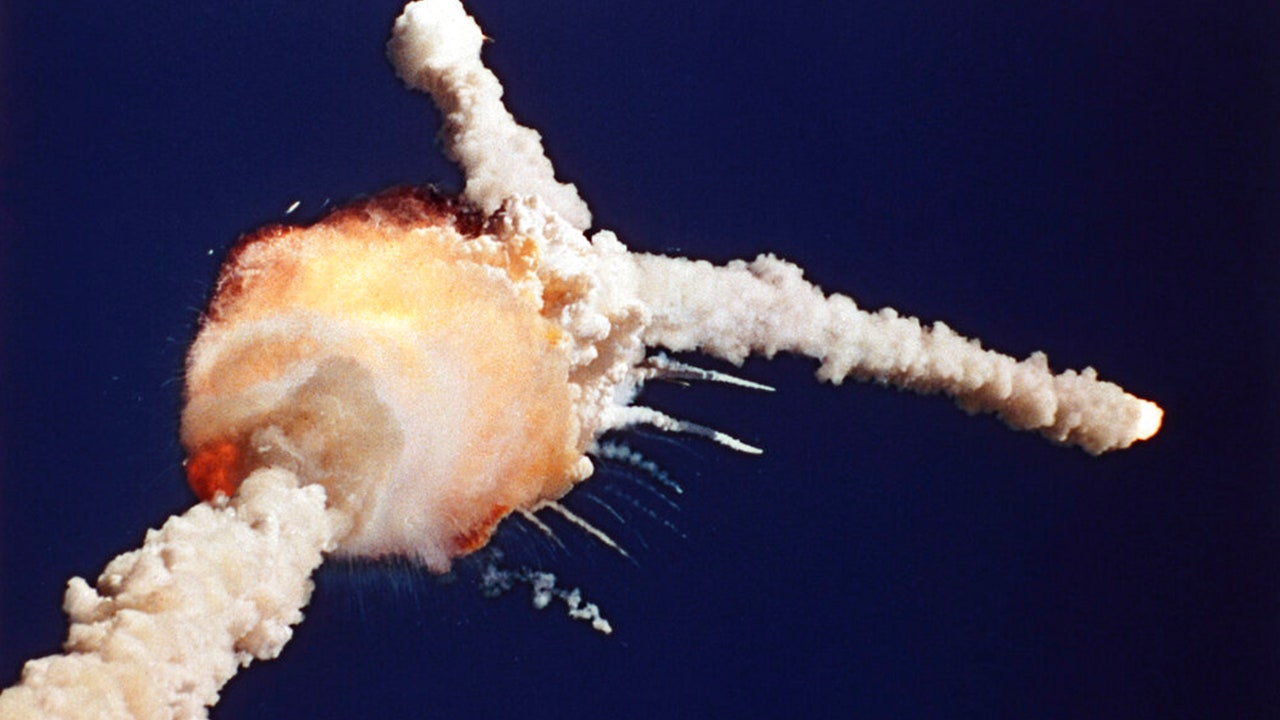

It was too cold. That’s the simplest, most devastating truth about the Challenger shuttle disaster 1986. On the morning of January 28, the temperature at Kennedy Space Center was hovering around 36 degrees Fahrenheit. For Florida, that’s freezing. For a massive piece of hardware like the Space Shuttle Challenger, it was a death sentence. Most people remember where they were. If you were a kid in the 80s, you were probably watching it in a classroom because Christa McAuliffe, a social studies teacher from New Hampshire, was on board. She was supposed to be the first "ordinary" citizen in space. Instead, 73 seconds after liftoff, the world watched a white cloud of smoke split into two jagged forks over the Atlantic.

The disaster wasn't just a "freak accident."

It was a failure of engineering, sure, but more than that, it was a failure of communication. NASA was under immense pressure to prove that space travel could be routine. They wanted to show that the shuttle could fly dozens of times a year. They had a schedule to keep. But machines don’t care about schedules.

The O-Ring Problem Nobody Wanted to Hear About

To understand what went wrong, you have to look at the Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs). These are the two white, pencil-like rockets strapped to the side of the main orange fuel tank. They are built in segments. Where those segments meet, there are joints sealed by two rubber rings called O-rings. Their entire job is to prevent hot, pressurized gases from leaking out during launch.

Rubber gets stiff when it’s cold. Think about a garden hose left out in the winter. It doesn't bend; it cracks.

Roger Boisjoly, an engineer at Morton Thiokol (the company that built the boosters), knew this. He had been sounding the alarm for months. He even wrote a memo famously stating that if the seal failed, it would result in "a catastrophe of the highest order." On the night before the launch, there was a frantic teleconference. Boisjoly and his colleagues pleaded with NASA to postpone. They pointed out that the O-rings had never been tested at temperatures below 53 degrees.

NASA officials were frustrated. Lawrence Mulloy, a NASA manager, reportedly snapped, "My God, Thiokol, when do you want me to launch — next April?" Under pressure, Thiokol management overrode their own engineers. They gave the "go" for launch. They ignored the data because they wanted to stay on the good side of their biggest client. It’s a classic case of groupthink that still gets taught in business ethics classes today.

73 Seconds of False Hope

When the engines ignited at 11:38 AM, a puff of black smoke immediately appeared near the bottom of the right SRB. This was the O-ring failing instantly. The cold had made it too brittle to seal the gap. Usually, aluminum oxides from the burning fuel would have plugged the leak, and for a few seconds, they actually did.

But then, Challenger hit a patch of extreme wind shear.

The shuttle was buffeted by the strongest winds ever recorded during a launch. This jarring motion knocked the temporary "plug" of aluminum oxide loose. A plume of flame erupted from the side of the booster like a blowtorch. It pointed directly at the main external fuel tank.

💡 You might also like: Twitter Video Download: What Most People Get Wrong

Inside the cockpit, the crew had no idea.

Commander Dick Scobee, Pilot Michael J. Smith, Mission Specialists Judith Resnik, Ellison Onizuka, Ronald McNair, and Gregory Jarvis, along with Christa McAuliffe, were doing their jobs. At 68 seconds, Scobee received the command, "Challenger, go at throttle up." He replied, "Roger, go at throttle up." Those were the last words.

At 73 seconds, the flame burned through the fuel tank. The liquid hydrogen ignited. The shuttle didn't actually "explode" in the way we see in movies. It was aerodynamic structural failure. The tank collapsed, releasing a massive fireball, and the orbiter was torn apart by the sheer force of the air hitting it at nearly twice the speed of sound.

The Tragic Fate of the Crew

There is a common misconception that the crew died instantly.

Evidence suggests otherwise. The crew cabin was built to be incredibly tough. It broke away from the rest of the shuttle in one piece. Investigators later found that several Personal Egress Air Packs (PEAPs) had been activated. These were manual emergency air supplies. Someone—likely Mike Smith—had reached over to turn them on for his crewmates.

The cabin continued to climb for miles before beginning a long, terrifying two-minute fall toward the ocean. There were no parachutes. There was no escape system. They hit the water at over 200 miles per hour. The impact was what killed them, not the initial breakup of the shuttle. It’s a haunting detail that makes the Challenger shuttle disaster 1986 feel much more personal and tragic than a mere technical malfunction.

The Rogers Commission and Richard Feynman’s Ice Water

President Ronald Reagan appointed the Rogers Commission to figure out what happened. It included big names like Neil Armstrong and Chuck Yeager. But the real star was physicist Richard Feynman. He hated the bureaucracy of the investigation. He wanted to see the hardware.

In a famous televised hearing, Feynman took a piece of the O-ring material, squeezed it with a C-clamp, and dropped it into a glass of ice water.

After a minute, he took it out. The rubber didn't bounce back. It stayed compressed. In one simple, unscripted moment, he showed the entire world exactly why the shuttle had been lost. He bypassed the hundreds of pages of NASA's technical jargon and proved that the "safety" of the shuttle was often based on wishful thinking rather than hard science.

📖 Related: What Was Invented by Thomas Edison and the Real Story Behind the Light Bulb

Feynman later wrote in his personal appendix to the report: "For a successful technology, reality must take precedence over public relations, for nature cannot be fooled."

Why It Still Matters in the Age of SpaceX

NASA stopped flying shuttles for nearly three years after the disaster. They redesigned the SRB joints. They added a bailout system (though it wouldn't have saved the Challenger crew in that specific scenario). They changed the culture—or so they thought.

Then came the Columbia disaster in 2003.

Again, it was a known issue (foam shedding) that managers chose to downplay. It seems that large organizations have a "memory" problem. As years pass, the lessons learned in blood start to fade, replaced by budget concerns and schedule pressure.

Today, we are in a new space race. Companies like SpaceX and Blue Origin are launching rockets at a pace NASA never dreamed of. The stakes are higher than ever. The Challenger shuttle disaster 1986 serves as a permanent warning for the private sector. When you start treating spaceflight as "routine," that’s exactly when it becomes most dangerous. You can't "move fast and break things" when there are humans on top of the rocket.

✨ Don't miss: iPhone 16 different sizes: Which one actually fits your hand?

Lessons You Can Actually Use

We aren't all rocket scientists, but the failures that led to 1986 happen in every office and every industry. Here is how to apply the "Challenger mindset" to your own work:

- Listen to the "No" in the room. If an expert on your team is telling you something is unsafe or won't work, don't ask them to "prove" it's dangerous. Ask yourself if you have proof that it's safe. Flip the burden of proof.

- Beware of "Normalization of Deviance." This is a term coined by sociologist Diane Vaughan regarding Challenger. It’s when you see a small problem, ignore it, and nothing bad happens—so you start to think the problem isn't a problem. Eventually, it catches up to you.

- Keep communication lines flat. The engineers knew the risk, but the top-level managers who made the final launch decision didn't have all the facts. If the person at the top doesn't know what the person at the bottom is worried about, the system is broken.

- Data over ego. Never let a deadline or a PR win dictate a technical decision. The "go" for launch should always be based on the hardware, not the calendar.

The wreckage of Challenger is now buried in sealed Minuteman missile silos at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station. It’s not a museum. It’s a grave and a reminder. Every time we look at the stars, we owe it to those seven individuals to remember that the cost of exploration is high, but the cost of silence is even higher.