The Central of Georgia Railway isn't just a collection of rusted spikes and rotted ties buried in the Georgia red clay. It’s actually one of the most significant pieces of American industrial history that most people—even those living right on top of its old right-of-way—barely understand. You’ve probably seen the old brick depots in towns like Savannah or Macon. Maybe you’ve even walked the "Rails-to-Trails" paths that replaced the tracks. But the sheer scale of what this company did for the South is staggering.

It started in 1833. That's early. Really early for railroads. Back then, it was the Central Rail Road and Canal Company of Georgia. They eventually dropped the canal part because, honestly, trains were just better. The goal was simple: get cotton from the interior of Georgia down to the port of Savannah. Without this specific line, Savannah might have ended up as a sleepy coastal town instead of the massive global shipping hub it is today.

The Empire of the Southeast

By the time the late 1800s rolled around, the Central of Georgia Railway was a behemoth. It wasn't just a Georgia thing. It stretched into Alabama and even reached up toward Chattanooga, Tennessee. This wasn't some minor branch line. We’re talking about a network that controlled thousands of miles of track.

If you look at the old maps from the early 20th century, the system looks like a giant spiderweb with Savannah at the center. It connected the coal mines of Birmingham to the textile mills of the Piedmont. It moved peaches. It moved timber. More importantly, it moved people. For decades, if you were traveling through the deep South, you were likely sitting on a Central of Georgia coach.

The company had a weirdly complicated relationship with other giants. For a while, the Illinois Central owned a massive stake in it. Then the Southern Railway—a huge rival—tried to buy it out. The Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) actually stepped in and said "no" because they were worried about a monopoly. It wasn’t until 1963 that the Southern Railway finally got permission to fully absorb it. Even then, the "Central" identity was so strong that they kept the name on locomotives for years.

📖 Related: Novotel Perth Adelaide Terrace: What Most People Get Wrong

The Savannah Shops: A Miracle of Engineering

You cannot talk about the Central of Georgia Railway without mentioning the Roundhouse Railroad Museum (now the Georgia State Railroad Museum) in Savannah. It is, quite literally, the most complete antebellum railroad repair facility in the United States. It's a miracle it survived the Civil War. When Sherman marched to the sea, he destroyed a lot of railroad infrastructure, but this complex largely escaped total annihilation.

Walking through there today is eerie. You see the massive turntable used to spin locomotives so they could enter the repair bays. You see the black-smith shops and the boiler rooms. It feels heavy. The air smells like old grease and coal dust even a century later. Most people don't realize that the Central of Georgia was one of the largest employers in the state for a long time. These shops weren't just for fixing engines; they were the high-tech hubs of the 19th century.

What happened to the passenger trains?

The "Nancy Hanks II" is probably the most famous name associated with the line. Named after a racehorse (which was named after Abraham Lincoln’s mother—it’s a whole thing), this train was the gold standard for travel between Savannah and Atlanta. It was fast. It was sleek. People loved it.

But then the 1950s happened.

👉 See also: Magnolia Fort Worth Texas: Why This Street Still Defines the Near Southside

Cars got cheaper. Eisenhower started the Interstate Highway System. Suddenly, taking a train from Macon to Atlanta seemed slow and restrictive compared to hopping in a Chevy and driving. The Nancy Hanks II made its last run in 1971. It was a sad day for Georgia railfans. When Amtrak took over most passenger services in the U.S., they didn't keep the Central's old routes. That’s why you can’t easily take a train from Savannah to Atlanta today. It’s a massive gap in our current infrastructure that wouldn't exist if the Central of Georgia were still at its peak.

Why the Route Matters Today

Freight still moves on these lines, mostly under the Norfolk Southern banner. If you stand by the tracks in a place like Tennille or Millen, you'll see the massive freight drags rolling through. They aren't carrying cotton anymore. Now it's intermodal containers, chemicals, and grain.

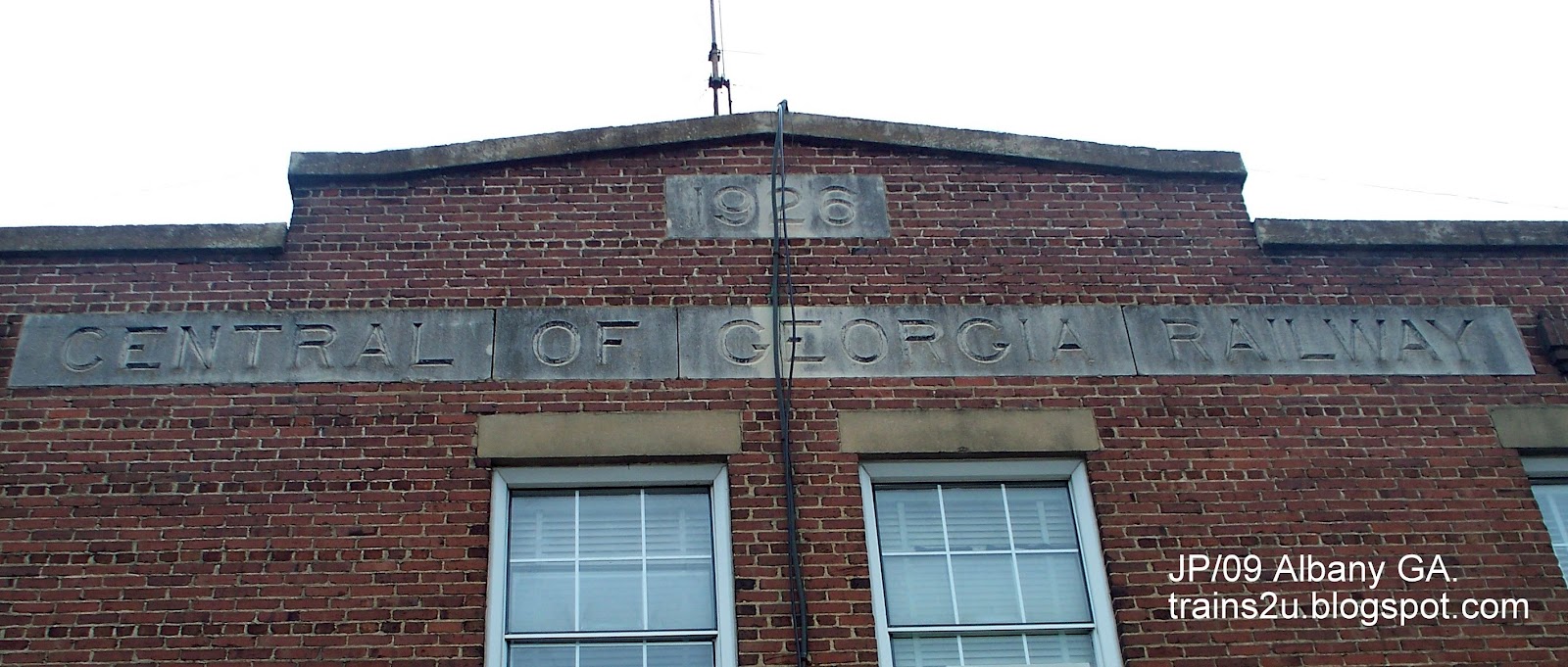

But the real value for most of us now is the preservation. The Central of Georgia Railway left behind an architectural legacy that defines the "look" of rural Georgia. Those small-town depots? They are often the only reason those towns survived the decline of the agricultural boom. Some have been turned into libraries. Others are museums or community centers.

- The Wadley Depot: A classic example of the company's brick architecture.

- The Miller County lines: Crucial for the peanut industry.

- The Macon Terminal: Once a bustling hub where the Central met its competitors.

The engineering was actually ahead of its time. They dealt with the "fall line" of Georgia—where the hilly Piedmont meets the flat Coastal Plain—with incredible precision. They built massive fills and deep cuts that are still stable today, 150 years later. That’s not luck. That’s elite 19th-century civil engineering.

✨ Don't miss: Why Molly Butler Lodge & Restaurant is Still the Heart of Greer After a Century

Misconceptions About the Civil War Era

A lot of people think the railroad was totally dead after 1865. Not true. While Sherman’s troops did the "Sherman’s Neckties" trick—heating rails over bonfires and twisting them around trees—the Central of Georgia rebuilt with terrifying speed. By 1867, they were back in business and actually expanding. They were resilient. They had to be because the entire economy of the South depended on them.

They also operated a steamship line! The Ocean Steamship Company of Savannah was a subsidiary. You could buy one ticket in Atlanta, ride the rail to Savannah, and hop on a luxury steamer to New York or Boston. It was a vertically integrated travel empire long before Delta or United existed.

How to Explore the History Yourself

If you want to actually see what’s left of the Central of Georgia Railway, don't just look at Wikipedia. You have to get out there. The history is physical. It’s in the dirt.

- Visit Savannah First: The Georgia State Railroad Museum is the "holy grail." You can see the original 1850s structures. They even have working steam locomotives on certain days. It's the best way to understand the scale of the operation.

- The Trail of the Silver Comet: While not all of it is Central of Georgia, many rail-trails in the region utilize these old corridors. Walking these paths gives you a sense of the "grade"—how flat the land had to be for a steam engine to pull a thousand tons of freight.

- Small Town Depots: Take a weekend drive through middle Georgia. Stop in towns like Millen, Waynesboro, or Gray. Look for the distinct brickwork of the old depots. Many have historical markers that explain what the specific town produced for the railroad.

- The Southern Museum of Civil War and Locomotive History: Located in Kennesaw, it houses "The General." While that locomotive is famous for the Great Locomotive Chase on the Western & Atlantic, the museum provides essential context for how all these Georgia lines interconnected.

The Central of Georgia Railway was eventually swallowed by Norfolk Southern, but its DNA is everywhere. The curves in the roads, the locations of our cities, and the very way Georgia trades with the world were all dictated by where these tracks were laid in the 1830s. It’s a ghost railroad that still haunts—and helps—the modern economy.

To truly appreciate it, look for the "Flying Turtle" logo on old equipment or in historical society archives. That logo symbolized a company that was slow to start but eventually outpaced everyone else in the region. It remains a masterclass in how infrastructure creates a state's destiny.