You're feeling that scratchy throat. It’s mid-November. You wonder if that "thing" going around the office is actually the flu or just a nasty cold that'll quit after a few days of Vitamin C and soup. This is exactly when most people start Googling the CDC flu map to see if their state is glowing red with high activity. But here is the thing: most of us are reading that map totally wrong. It isn't a weather radar. It doesn't show you where the flu is going to be tomorrow afternoon.

It's actually a historical record of where the flu was about a week ago.

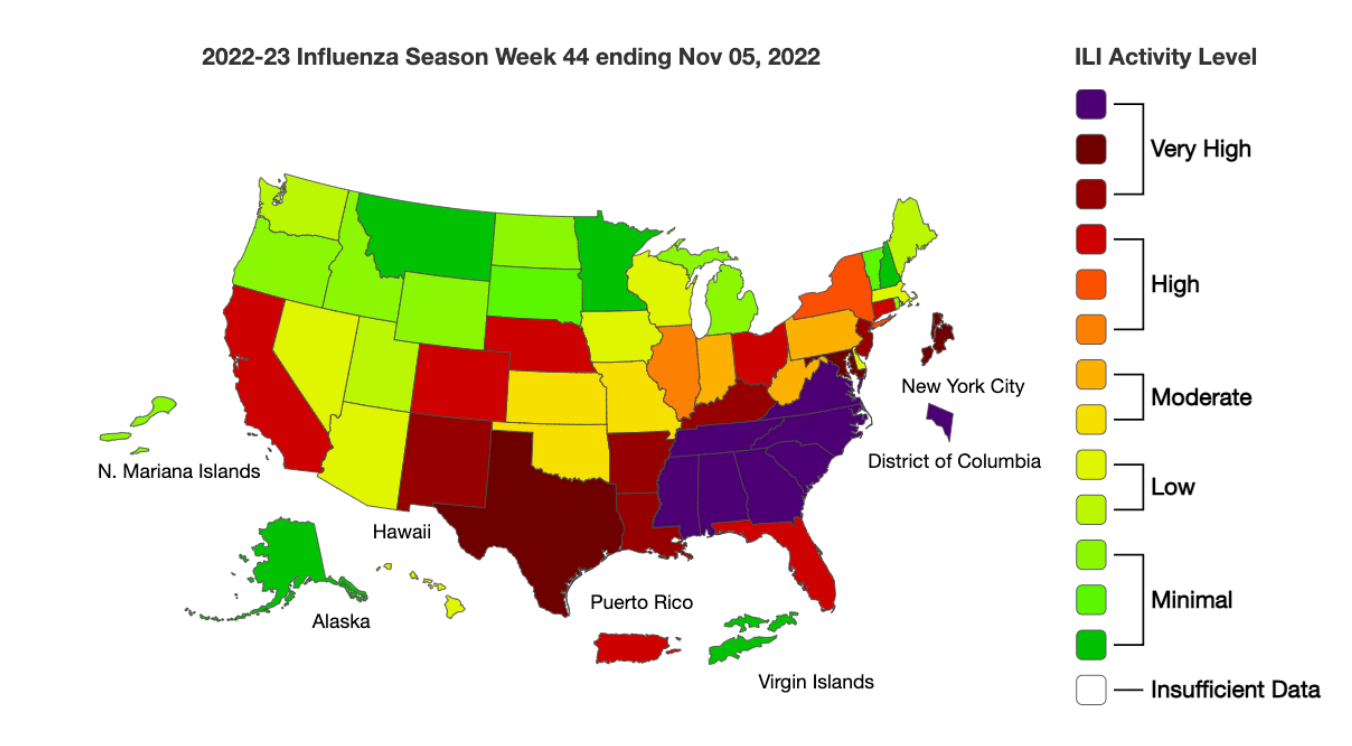

Data lags. That is the reality of public health surveillance in a country as massive as the United States. When you look at the Weekly U.S. Influenza Surveillance Report—which the pros call "FluView"—you’re seeing a massive, complex aggregation of clinical lab results, emergency room visits, and even death certificates. It takes time to process that. If the map shows your state is in the "Purple" or "Very High" category, the virus has likely already peaked or is currently tearing through your local elementary schools. You're seeing the wake of the ship, not just the bow.

How the CDC Flu Map Actually Works (And Why It’s Not a Forecast)

The map is basically a snapshot of ILI. That stands for Influenza-Like Illness. Doctors use this term because, honestly, they don't test every single person who walks in with a fever and a cough. Testing is expensive. It takes time. Instead, the CDC tracks how many people are visiting healthcare providers for a fever of 100°F or higher, plus a cough or a sore throat.

If a huge percentage of people in Atlanta are hitting the ER with those symptoms, Georgia starts turning a darker shade of red on the map.

The ILINet System

The backbone of this whole operation is the Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network (ILINet). It consists of over 3,500 healthcare providers across all 50 states, Puerto Rico, the District of Columbia, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. These people are the unsung heroes of data. Every week, they report the total number of patients seen for any reason and the number of those patients with ILI by age group.

But it’s not just about raw numbers. The CDC compares current activity to a "baseline." This is why a "High" level in Maine might look different than a "High" level in Florida. The baseline is calculated based on the previous three seasons of non-influenza weeks. It’s a way of saying, "Compared to what is normal for this time of year in this specific place, how bad is it?"

The Weird Logic of "Activity Levels"

The map uses a scale from 1 to 13.

- Minimal (Levels 1-3)

- Low (Levels 4-5)

- Moderate (Levels 6-7)

- High (Levels 8-10)

- Very High (Levels 11-13)

You might see your state jump from a 4 to a 9 in a single week. That’s a massive spike. It usually means the virus has hit the "exponential growth" phase. One kid brings it to a birthday party, and by Tuesday, half the class is out. By Thursday, the parents are calling out of work. By the time that data reaches the CDC and gets plotted on the CDC flu map, the "outbreak" is already well underway.

Kinda scary? Sorta. But it’s the best tool we have for resource allocation. Hospitals use this data to decide if they need to cancel elective surgeries or set up "flu tents" to handle the overflow in the ER.

💡 You might also like: Why Your Heart Skips a Beat: The Reality of Palpitations and When to Actually Worry

The Different Types of Flu on the Radar

Not all flu is created equal. The map doesn't differentiate between strains at a glance, but the deeper reports do. Usually, we're talking about Influenza A and Influenza B.

Historically, Influenza A (like H1N1 or H3N2) is the big bad wolf. It tends to cause more severe seasons and more hospitalizations. H3N2, in particular, is a beast for the elderly. Influenza B, on the other hand, often shows up later in the season. It’s sometimes called the "spring flu," though that’s a bit of a misnomer. It can be just as miserable, especially for children.

In some years, like the 2019-2020 season, we saw an unusual "double peak." Influenza B hit early and hard in December, which was weird. Then, just as that started to fade, Influenza A took over. The map stayed red for months. It felt like the season that would never end.

Why Your Local Map Might Be Lying to You

Okay, "lying" is a strong word. Let's say "obscuring the truth."

The CDC flu map shows state-level data. But states are big. If you live in upstate New York, your actual risk might be near zero, even if New York City is currently a viral hotspot that’s turning the whole state "Very High" on the map.

Some states provide county-level data on their own Department of Health websites. If you really want to know what’s happening in your backyard, you have to go deeper than the national map. Look at the "Percent Positivity" from local labs. If 25% of the flu tests coming back from your local clinic are positive, it doesn't matter what the color of the state is on the CDC website—you are in the thick of it.

The Role of Wastewater Surveillance

This is the "new" cool thing in public health. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, we've gotten much better at checking our poop for viruses.

Wastewater monitoring is often a leading indicator. People shed the virus in their waste before they feel sick enough to go to the doctor. Sometimes, the wastewater levels will spike 4 to 7 days before the CDC flu map shows an uptick in ILI. It’s like a biological early warning system. While the CDC is integrating this more, it’s still a separate data stream for many people. If you see flu DNA spiking in your city's sewage, buy your tissues and elderberry syrup now.

Hospitalization and Mortality: The Grim Stats

The map tracks activity, but the "FluView" report tracks the consequences.

The CDC estimates that influenza has resulted in between 9 million and 41 million illnesses annually since 2010. The death toll is anywhere from 12,000 to 52,000 people a year. These aren't just numbers; they are a reflection of how the virus interacts with a population that has varying levels of immunity.

When the map stays "Very High" for more than 3 or 4 weeks, the hospitalization rates for people over 65 usually skyrocket. This puts a massive strain on the healthcare system. It's not just about the flu; it's about the fact that if you have a heart attack during a peak flu week, the ER might be too crowded to see you immediately. That is the secondary danger of the flu map's red zones.

Pediatric Deaths: The Stat No One Wants to Talk About

Every year, the CDC tracks pediatric deaths. It is a heartbreaking metric. In a "good" year, it might be 30 or 40. In a "bad" year, it can exceed 200.

A striking fact from CDC data: about 80% of the children who die from the flu were not fully vaccinated. This is why the map is so vital for pediatricians. When they see activity rising, they start sending out those "get your shot" reminders with a lot more urgency.

The Flu Vaccine and the "Match"

Every February, the World Health Organization (WHO) meets to decide which strains should go into the next year's vaccine. They have to guess. They look at what’s circulating in the Southern Hemisphere (like Australia) during their winter (our summer).

Sometimes they nail it. Sometimes the virus mutates, a process called "antigenic drift."

If the virus "drifts" away from the vaccine, you might see the CDC flu map stay red even in areas with high vaccination rates. This doesn't mean the vaccine is useless. It usually still prevents the most severe outcomes—like ending up on a ventilator—but it might not stop you from feeling like you were hit by a truck for five days.

Common Misconceptions About the Map

People think "Moderate" means they are safe. It doesn't.

"Moderate" just means the levels are higher than the baseline but not yet at "crisis" levels for the healthcare system. You can still catch a life-altering case of the flu in a "Low" activity state. Transmission is happening everywhere, all the time, during the winter months.

👉 See also: Calories in a Hash Brown McDonald's: What You're Actually Eating for Breakfast

Another big one: People think the map shows "Stomach Flu."

Nope.

The flu is respiratory. Gastroenteritis (what people call stomach flu) is usually Norovirus or something else entirely. The CDC flu map has nothing to do with vomiting or diarrhea unless those are secondary symptoms of a massive systemic respiratory infection, which is rare in adults.

What You Should Actually Do With This Information

Don't just stare at the map and panic. Use it as a trigger for behavior change.

If the map is showing an upward trend in your region:

- Wash your hands. Really wash them. 20 seconds. Sing the song.

- Stop touching your face. This is the hardest habit to break, but it’s how the virus gets from the doorknob to your mucus membranes.

- Get the shot. Even if it’s late in the season. January isn't too late. February isn't too late.

- Check your "sick day" stash. Do you have Ibuprofen? Do you have a thermometer that actually works? Do you have enough electrolyte drinks?

The Future of Tracking: AI and Beyond

We are getting better at this. Researchers are now using Google search trends and social media sentiment to try and "nowcast" the flu. If a thousand people in Des Moines suddenly search for "body aches and chills," there’s a good chance an outbreak is starting.

The CDC is also moving toward more "molecular" surveillance. They want to know exactly which sub-clades of the virus are moving through which cities. This could eventually lead to "precision" public health warnings. Imagine getting a notification on your phone: "H3N2 is currently high in your zip code; the current vaccine is a 70% match. Take precautions."

We aren't quite there yet. For now, we have the map.

Actionable Steps for Flu Season

- Bookmark the Weekly FluView. Check it every Friday afternoon when it's updated. This gives you a head start on your weekend plans. If things are looking "High," maybe skip the crowded indoor concert.

- Look at the "Age Group" breakdown. The CDC provides data on who is getting hit hardest. If it's hitting kids specifically, be extra careful with school events.

- Trust your local DOH. Your state’s Department of Health website often has a more granular version of the CDC flu map. Find it.

- Listen to your body. If you feel "off" and the map is red, stay home. Don't be the person who brings the "Moderate" activity level to "High" at your local gym.

The map is a tool for the public, but it's a shield for the healthcare system. By understanding that the red colors mean the virus is already there—not just coming—you can make better choices about your health and the health of the people around you. Stay hydrated, keep your distance from "the office cougher," and use the data to stay one step ahead of the season.

Next Steps for You:

Check the current CDC flu map status for your specific region today. If your state is in the "Moderate" to "Very High" range, ensure your household is stocked with fever-reducers and a working thermometer. If you haven't received a seasonal vaccination, consult your pharmacist about current strain matches for this year's circulating viruses. For more localized data, search for your state's "Department of Health Respiratory Virus Surveillance" report to see county-level trends that the national map might overlook.