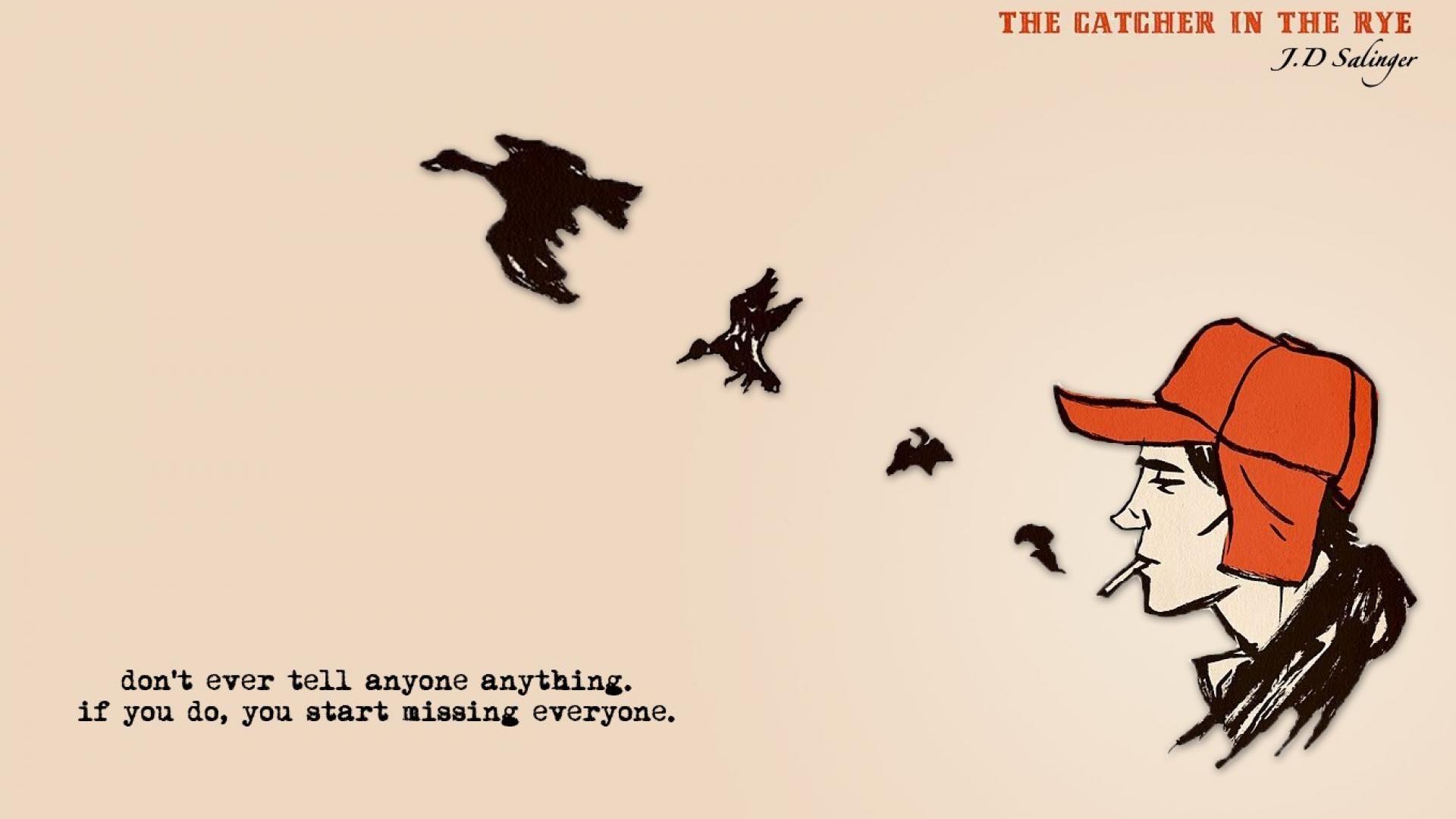

If you haven't read The Catcher in the Rye since high school, you probably remember Holden Caulfield as a whiny kid in a red hunting hat who called everyone a "phony." It’s the classic trope. But honestly, reading J.D. Salinger’s 1951 masterpiece as an adult is a completely different trip. You realize pretty quickly that Holden isn’t just some privileged brat wandering around New York City; he’s a grieving, traumatized teenager desperately trying to find a shred of authenticity in a world that feels like a giant performance.

J.D. Salinger didn’t just write a book. He captured a specific frequency of human loneliness.

Even in 2026, the novel remains one of the most frequently challenged and banned books in American libraries. Why? People cite the profanity or the "immoral" behavior, but really, it's because the book is a mirror. It forces us to look at the transition from childhood to adulthood and admit that it's mostly just a process of losing your soul piece by piece to social conventions.

The Mystery of J.D. Salinger and the Birth of Holden

Salinger was a bit of a ghost. After the massive success of the novel, he basically vanished into the woods of Cornish, New Hampshire. He wasn't doing it for the "aesthetic" like some modern influencer might. He was legitimately haunted.

He actually carried the first few chapters of The Catcher in the Rye with him while he was fighting in World War II. Think about that. He was landing on Utah Beach on D-Day with Holden Caulfield in his pocket. Experts like biographer Ian Hamilton have pointed out that the cynicism and the deep-seated "edge" in the writing likely came from Salinger’s own shell-shocked perspective. When Holden talks about the "phoniness" of the world, it’s not just teenage angst—it’s the perspective of a man who saw the literal horrors of war and then came home to find people obsessing over movies and social status.

The book was published by Little, Brown and Company on July 16, 1951. It wasn't an immediate unanimous hit. Some critics hated it. They thought it was "predictable" or "vulgar." But the youth? They grabbed onto it like a lifeline. It sold millions of copies because, for the first time, a book spoke the way teenagers actually spoke—messy, repetitive, and full of contradictions.

📖 Related: Gwendoline Butler Dead in a Row: Why This 1957 Mystery Still Packs a Punch

What Everyone Gets Wrong About the Title

Most people think "the catcher in the rye" is some poetic, high-brow metaphor Salinger cooked up to sound deep. It’s actually based on a mistake. Holden mishears a Robert Burns poem, "Comin' Thro' the Rye."

The line is actually "If a body meet a body, comin' thro' the rye," but Holden hears it as "If a body catch a body."

He builds this whole mental image of thousands of little kids playing in a field of rye on the edge of a cliff. He wants to be the guy who catches them before they fall off the edge. It’s a literal manifestation of his desire to stop time. He doesn't want kids to fall over the "cliff" of adulthood and become the very phonies he despises. It’s heartbreakingly sweet and totally impossible.

The Anatomy of a Phony

Holden uses the word "phony" about 44 times in the book. It’s his catch-all for anything that lacks a soul.

- He hates the movies because they provide a fake version of reality.

- He hates his brother D.B. for "prostituting" himself by writing for Hollywood.

- He hates the guys at Pencey Prep who talk about how many girls they've "necked" with.

But here’s the nuance: Holden is also a total liar. He admits it in the first few pages. "I'm the most terrific liar you ever saw in your life." This is what makes The Catcher in the Rye a masterpiece of the "unreliable narrator." You can't take everything he says at face value. He’s judging everyone else for being fake while he’s walking around under a fake name, telling stories to strangers on trains, and pretending to be older than he is.

👉 See also: Why ASAP Rocky F kin Problems Still Runs the Club Over a Decade Later

He's a hypocrite. And that’s the point. We’re all hypocrites when we’re trying to figure out who the hell we are.

The Dark Side of the Legacy

We have to talk about the "Mark David Chapman" factor. It’s the elephant in the room whenever this book comes up in a serious conversation. In 1980, after Chapman shot John Lennon, he was found sitting on the curb reading his copy of the book. He even wrote "This is my statement" inside the cover.

This led to decades of people associating the book with violence or mental instability. John Hinckley Jr., who tried to assassinate Ronald Reagan, also had a copy.

But blaming Salinger’s book for those events is like blaming the pavement for a car crash. The book deals with alienation. For someone already on the brink, that resonance can be dangerous, but for the other 65 million people who have read it, it's just a way to feel less alone in their own skin. The book doesn't advocate for violence; it advocates for protecting innocence.

Why We Still Care in 2026

You might think a book about a kid in the 1940s wouldn't resonate in a world of TikTok and AI. You’d be wrong.

✨ Don't miss: Ashley My 600 Pound Life Now: What Really Happened to the Show’s Most Memorable Ashleys

In fact, Holden’s obsession with "phoniness" is more relevant now than it was in 1951. We live in the era of the curated life. Everything is a brand. Everyone is performing. Holden would have hated Instagram. He would have lost his mind over LinkedIn "thought leaders."

The alienation Holden feels is the same alienation a 16-year-old feels today when they realize that the adults around them are just playing roles.

The Structure of the Narrative

The book isn't a traditional plot-heavy story. It’s a picaresque. It’s just Holden moving through space over the course of a few days.

- The Departure: He gets kicked out of Pencey Prep (again).

- The City: He wanders New York, checks into a dive hotel, tries to hire a prostitute but just wants to talk, and visits his old teachers.

- The Breakdown: He sneaks into his own house to see his sister Phoebe.

- The Carousel: The climax, such as it is, happens at the zoo.

Watching Phoebe on the carousel is the only time Holden seems truly happy. She’s reaching for the "gold ring"—a symbol of taking risks and growing up—and for once, Holden decides not to stop her. He realizes you have to let kids reach for the ring, even if they might fall. It’s his moment of growth. He accepts the inevitable.

Actionable Insights for the Modern Reader

If you're going to dive into The Catcher in the Rye for the first time—or the tenth—keep these things in mind to actually "get" what Salinger was doing.

- Look for the Allie references. Allie was Holden’s brother who died of leukemia. Almost every "crazy" thing Holden does is actually a symptom of unresolved grief. The red hunting hat? It’s a way to feel connected to Allie’s red hair.

- Don't try to like Holden. You don't have to. He’s annoying. He’s a snob. But try to understand him.

- Pay attention to the ducks. Holden keeps asking where the ducks in Central Park go in the winter. It’s a goofy question, but it’s really about his fear of disappearing. He wants to know that even when things get cold and dark, there’s a place to go.

- Read the "Esme" story next. If you finish the book and want more, read Salinger’s short story For Esme—with Love and Squalor. It’s a more direct look at how war breaks a person and how a child’s innocence can potentially put them back together.

The Catcher in the Rye isn't a "how-to" guide for being a rebel. It’s a "how-to" guide for being human in a world that often feels plastic. It’s messy, it’s profane, and it’s deeply uncomfortable. That’s exactly why it hasn't been forgotten.

Next Steps for Deeper Understanding

To truly appreciate the impact of the novel, your next step should be exploring the context of 1950s post-war America. Read up on the "Silent Generation" and the stifling social conformity of the era; it makes Holden’s rebellion feel much more like a survival tactic than a temper tantrum. You might also want to look into Salinger's Franny and Zooey to see how his themes of spiritual searching evolved after Holden. Finally, visit a local library and ask about their history with the book—it's a great way to see how "dangerous" ideas are still being debated in your own community.