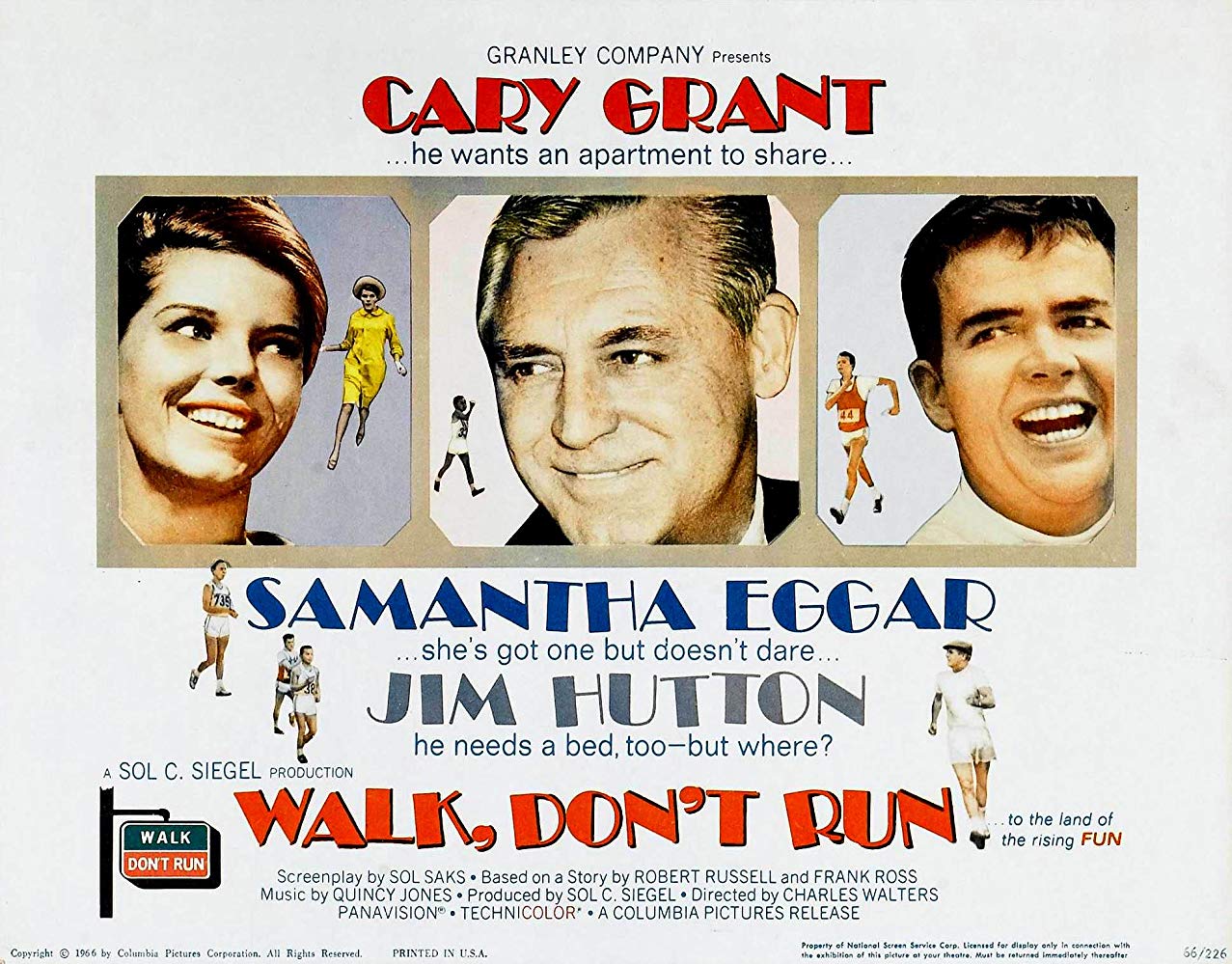

If you’ve ever watched a movie and felt like you were witnessing the end of an era, you were probably watching a film from the mid-sixties. Hollywood was changing. Fast. The old guard of suave, mid-Atlantic accented leading men was being pushed out by the grit of the New Hollywood movement. But before the door closed entirely, we got one last charming, breezy masterpiece set against the backdrop of the Tokyo Olympics. Honestly, the cast of Walk Don’t Run 1966 is what makes this movie more than just a footnote in cinematic history. It was Cary Grant's final bow. He knew it, the director knew it, and if you watch closely, you can see him passing the torch in real-time.

The Legend Steps Aside: Cary Grant as Sir William Belvedere

It’s weird to think of Cary Grant as a matchmaker instead of the guy getting the girl. For decades, he was the guy. The one who got Audrey Hepburn, Grace Kelly, and Deborah Kerr. But in this remake of the 1943 film The More the Merrier, Grant intentionally took the "Charles Coburn role." He plays Sir William Belvedere, an English industrialist who arrives in Tokyo for the 1964 Olympics and finds himself without a hotel room.

He ends up subletting half of an apartment from a young Englishwoman, then proceeds to sublet half of his half to an American athlete. It’s a classic farce setup. Grant is 62 here. He looks fantastic, of course, but there’s a self-awareness in his performance. He isn't trying to be the 30-year-old romantic lead anymore. Instead, he uses that legendary comedic timing to push the two younger leads together.

You’ve gotta appreciate the humility there. Most stars of his caliber would have fought for a script where they still got the girl. Grant didn’t. He reportedly turned down roles in My Fair Lady and The Music Man around this time because he felt he was too old. By the time he joined the cast of Walk Don’t Run 1966, he was done. This was his swan song, and he played it with a mischievous, "Grandpa-matchmaker" energy that feels incredibly warm.

Samantha Eggar: The Woman Caught in the Middle

Samantha Eggar plays Christine Easton, the woman who made the mistake of renting out her space. Eggar was coming off a massive high after her Oscar-nominated performance in The Collector (1965). She was the "it" girl of the moment. In this film, she’s tasked with being the straight woman to the chaos surrounding her.

She's British, she's organized, and she's engaged to a very boring diplomat played by John Standing. Eggar’s chemistry with Grant is lovely—it’s more like a father-daughter or mentor-protege vibe. She brings a necessary groundedness. Without her acting as the "voice of reason," the movie would just be three people shouting in a tiny apartment.

👉 See also: Cuatro estaciones en la Habana: Why this Noir Masterpiece is Still the Best Way to See Cuba

Interestingly, Eggar has mentioned in interviews that working with Grant was an education in professionalism. He was obsessive about the details. He cared about the lighting, the way the suits fit, and the rhythm of the jokes. You can see that polish in her performance; she holds her own against a titan.

Jim Hutton and the Passing of the Torch

Then there’s Jim Hutton. He plays Steve Davis, the American Olympic walker (yes, race walking is the sport here, which is inherently funny). Hutton was often compared to a young Jimmy Stewart. He was tall, lanky, and had this "aw-shucks" American charm.

Grant personally liked Hutton. In fact, there’s a persistent story that Grant saw Hutton as a potential successor for the kind of light comedy he excelled at. In the film, Grant’s character literally strips Hutton down to his shorts and pushes him into a room with Eggar. It’s a metaphorical passing of the baton. Hutton is great here. He’s clumsy but sincere.

Sadly, Hutton never quite hit the "Cary Grant" levels of superstardom, though he later found massive success on TV as Ellery Queen. But in 1966, he was the perfect foil for Grant's sophisticated meddling. Watching them together is a treat because you’re seeing two different styles of screen acting—the old-school precision of the 30s vs. the more relaxed, naturalistic vibe of the 60s.

The Supporting Players Who Made Tokyo Feel Real

While the trio of Grant, Eggar, and Hutton carries the weight, the rest of the cast of Walk Don’t Run 1966 fleshes out this strange, transitional version of Tokyo.

✨ Don't miss: Cry Havoc: Why Jack Carr Just Changed the Reece-verse Forever

- John Standing (Julius Haversack): He plays the fiancé. He’s the guy you’re supposed to want the heroine to leave. He does "stuffy and preoccupied" perfectly.

- Miiko Taka (Aiko Kurawa): You might remember her from Sayonara with Marlon Brando. Here, she adds a layer of local authenticity to the film.

- Ted Hartley (Yuri Andreyovitch): He plays a Russian athlete. It’s a small role, but it highlights the Cold War tensions that were always bubbling under the surface of the Olympics, even in a rom-com.

Why the Location Was the Secret Fourth Star

Director Charles Walters, who did High Society, decided to shoot on location in Tokyo. This was a big deal. The city was rebuilding, showing off its post-war modernization. The film captures a very specific moment in Japanese history.

You see the crowded streets, the mix of traditional architecture and mid-century modern interiors. The apartment itself is a character. It’s tiny. It’s cramped. It forces the cast of Walk Don’t Run 1966 to physically interact in ways that drive the comedy. Grant is constantly ducking under doorways or squeezing past people. It’s physical comedy at its most refined.

The Mystery of Cary Grant’s Retirement

People always ask: why did he quit after this? He was still a top box-office draw. He could have worked for another twenty years.

The truth? He had a daughter, Jennifer, in 1966. He wanted to be a father more than he wanted to be a movie star. He also realized that the "New Hollywood"—the world of The Graduate and Easy Rider—didn't have a place for a man who refused to look unkempt on screen. He left on a high note. Walk Don’t Run isn't his best movie (that’s probably North by Northwest or The Awful Truth), but it’s his most relaxed. He looks like he’s having fun.

Technical Mastery Behind the Scenes

It wasn't just the actors. The score by Quincy Jones—yes, that Quincy Jones—is incredible. It’s jazzy, light, and perfectly captures the energy of a city on the move. It’s one of those rare 60s scores that doesn't feel dated. It feels "cool."

🔗 Read more: Colin Macrae Below Deck: Why the Fan-Favorite Engineer Finally Walked Away

The cinematography by Christopher Challis makes Tokyo look like a neon wonderland. Even the mundane scenes of race walking are shot with a dynamic energy. Challis was a legend, having worked on The Red Shoes and Tales of Hoffmann. He brought a lush, Technicolor sensibility to a movie that could have just been a static stage play.

Misconceptions About the Movie

Some people think this is a sports movie. It isn't. The Olympics are just a plot device to explain why there are no hotel rooms. If you go in expecting a gritty look at athletic competition, you’ll be disappointed.

Others think it’s a remake of a movie no one saw. Actually, The More the Merrier was a huge hit during WWII. The 1966 version updates the setting from a housing shortage in D.C. to a housing shortage in Tokyo. It’s a "transposition" that actually works because the themes of crowded cities and accidental intimacy are universal.

What You Should Take Away From It

If you’re going to revisit the cast of Walk Don’t Run 1966, do it for the vibes. It’s a "comfort food" movie. It represents a time when movies were meant to be pleasant, well-dressed, and slightly absurd.

Practical Steps for Your Next Rewatch:

- Watch "The More the Merrier" (1943) first. It helps you appreciate the changes they made to the script and how Grant interpreted the role differently than Charles Coburn did.

- Look at the background. The footage of 1964 Tokyo is historically significant. It’s a documentary of a lost city in many ways.

- Pay attention to Grant’s wardrobe. Even when he’s playing a guy who’s "roughing it," he’s wearing some of the finest tailoring ever seen on film. He actually provided a lot of his own clothes for his movies.

- Listen to the Quincy Jones score. It’s available on most streaming platforms and stands alone as a great piece of mid-century jazz.

The film is a reminder that you don't always need a massive explosion or a high-stakes villain to make a movie work. Sometimes, you just need three talented people stuck in an apartment, trying to figure out who sleeps where. It was the end of the road for Cary Grant, but man, what a way to go out. He didn't fade away; he just walked—don't run—off into the sunset.

Next Steps for Film History Buffs:

Check out the Criterion Channel’s collection on "New Hollywood" to see exactly what kind of movies started winning Oscars the year after Grant retired. It provides a stark contrast to the polished world of Sir William Belvedere. You can also look into the history of the 1964 Tokyo Olympics to see how much of the film's "crowded city" vibe was based on reality versus Hollywood set design.