Black and white film has a way of hiding things in the shadows that color just can't replicate. When you look at the cast of the original Cape Fear, you aren't just looking at a list of 1960s Hollywood icons; you're looking at a masterclass in psychological friction. Most people today immediately think of Robert De Niro’s tattooed, over-the-top Max Cady from the 1991 Scorsese version. He was loud. He was monstrous. But Robert Mitchum? Mitchum was something else entirely. In the 1962 original, directed by J. Lee Thompson, the horror wasn't in the shouting. It was in the stillness.

It’s actually wild how much the 1962 version relies on the sheer presence of its leads rather than special effects. Gregory Peck plays Sam Bowden, the "good" lawyer, but even he feels a bit frayed at the edges. You've got this collision between the ultimate cinematic hero of the era and the ultimate cinematic anti-hero. It’s a miracle the film even got past the censors of the time, considering how much it hinted at sexual violence—a topic that was basically radioactive in early '60s cinema.

The Men Behind the Malice: Mitchum vs. Peck

Robert Mitchum didn't need to hit the gym to be scary. He just had to lean against a wall. As Max Cady, he brought a greasy, low-life confidence that made audiences feel like they needed a shower. Interestingly, Mitchum was initially hesitant to take the role. He reportedly told the director that the character was "too much of a bastard." But once he signed on, he leaned into the predatory nature of the role with a terrifying casualness. He used his real-life reputation as a Hollywood "bad boy" to fuel the performance.

Gregory Peck, on the other hand, was the moral compass of America. Coming off the heels of To Kill a Mockingbird, he was the personification of justice. That’s what makes his role in the cast of the original Cape Fear so vital. If you put a lesser actor against Mitchum, the movie falls apart because Cady would just steamroll them. Peck provides the necessary weight. He’s the immovable object to Mitchum’s unstoppable, degenerate force.

The chemistry between them wasn't just professional; it was physical. During the filming of the final fight in the Georgia marshes, Mitchum—who was famously strong—actually struck Peck by accident. Peck didn't break character. He later said that he felt the blow for days, but it added a level of realism to Bowden’s desperation that you simply cannot fake with a stuntman.

✨ Don't miss: Why October London Make Me Wanna Is the Soul Revival We Actually Needed

Polly Bergen and the Burden of the Victim

Polly Bergen played Peggy Bowden, and honestly, her performance is often unfairly sidelined when people talk about this movie. She had to portray a specific kind of mid-century housewife terror. In the 1960s, the "damsel in distress" trope was everywhere, but Bergen gave Peggy a sense of mounting atmospheric dread. She wasn't just screaming; she was watching her domestic safety evaporate.

There’s a scene where Cady corners her, and the way Bergen uses her eyes to convey the realization that her husband cannot protect her is haunting. It’s a shift from confidence to total vulnerability. While the remake gave the wife character more of a "flawed marriage" subplot, the 1962 original kept it focused on the external threat. This made Peggy’s isolation feel even more claustrophobic.

Supporting Players Who Built the Tension

You can't talk about the cast of the original Cape Fear without mentioning Telly Savalas. Long before he was Kojak, he was playing private detective Charles Sievers. Savalas brings a cynical, street-smart energy to the film that contrasts with Peck’s idealistic lawyer. He’s the one who tells Bowden what he doesn't want to hear: that the law won't save him.

Then there’s Lori Martin as Nancy Bowden, the daughter. This was the most controversial part of the casting. The threat Cady poses to the child is the dark heart of the movie. Martin had to play a role that was incredibly mature for her age, navigating scenes that suggested a level of predatory behavior that was almost unheard of in 1962. The British Board of Film Censors actually demanded 161 cuts before they would let the movie be shown in the UK, mostly due to the implications involving the daughter.

🔗 Read more: How to Watch The Wolf and the Lion Without Getting Lost in the Wild

- Martin Balsam as Mark Dutton: The police chief caught between his friendship with Bowden and the limitations of his badge.

- Jack Kruschen as Dave Grafton: A small-town lawyer who represents the kind of "hired gun" Cady uses to stay on the streets.

- Barrie Chase as Diane Taylor: The woman Cady brutally attacks early in the film, proving to the audience (and Bowden) exactly what he is capable of.

Why the 1962 Cast Hits Differently

The 1991 remake is a great movie, but it's a "movie-movie." It's stylized. The 1962 film feels like a police report. The cast of the original Cape Fear didn't have the benefit of a Bernard Herrmann score that was re-recorded in high-fidelity (though they had the original haunting score). They had to rely on the "theatricality of the mundane."

Mitchum’s Cady doesn't look like a supervillain. He looks like a guy you'd see at a bus station. That’s why it works. It taps into the primal fear that a "nobody" can ruin your life just because he has the time and the spite to do it.

The Legend of the "Cameo" Full Circle

One of the coolest bits of trivia for film buffs is how the 1991 version paid homage to this original lineup. Martin Scorsese brought back Gregory Peck, Robert Mitchum, and Martin Balsam for his remake.

Peck played the sleazy lawyer Lee Heller—basically the opposite of his 1962 character. Mitchum played Lieutenant Elgart, the weary cop. Seeing them share the screen one last time was a "passing of the torch," but for many purists, their 1962 performances remain the definitive versions. It’s a rare case where the original actors were so iconic that the remake felt it had to include them just to gain legitimacy.

💡 You might also like: Is Lincoln Lawyer Coming Back? Mickey Haller's Next Move Explained

How to Appreciate the 1962 Original Today

If you're going to dive into this classic, don't just watch it for the plot. Watch the body language. Notice how Mitchum occupies space. Notice how Peck’s posture degrades as the movie progresses.

- Watch the "Egg Scene": Look at how Mitchum uses a simple prop—a jar of eggs—to create a sense of disgusting intimacy and threat.

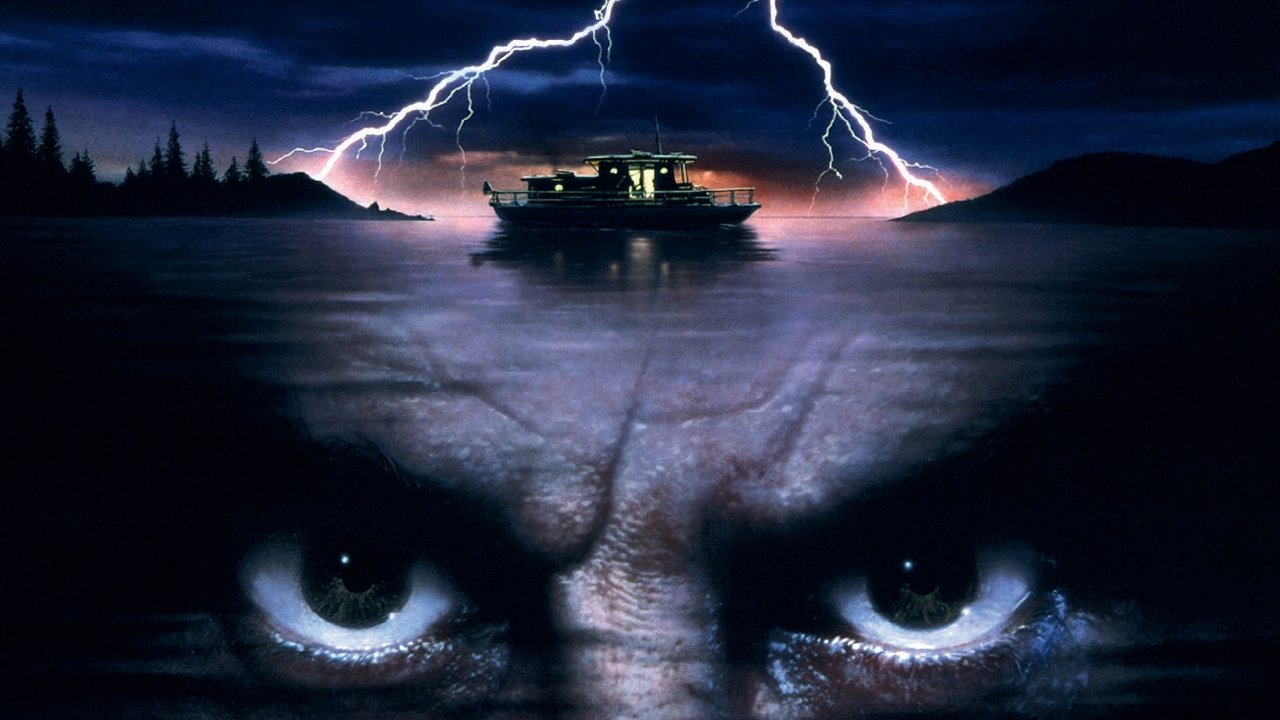

- Compare the Finales: The 1962 ending is much more grounded than the house-boat-on-fire spectacle of the 90s. It feels more like a desperate scuffle in the dirt.

- Check the Lighting: Pay attention to the noir influences. The shadows are practically extra characters in the cast of the original Cape Fear.

The 1962 Cape Fear isn't just a thriller; it's a document of a turning point in Hollywood. It was the moment the "perfect" American family realized that the monsters weren't just in horror movies—they were walking down the street in Panama hats, whistling a tune, and waiting for the sun to go down.

To truly understand the impact, you have to look past the modern tropes. Forget the gore. Forget the jump scares. Focus on the psychological warfare. The way Mitchum delivers his lines with a Southern drawl that feels like sandpaper on silk is something no remake could ever truly capture. It is a masterclass in restraint, proving that what you don't see—and what an actor doesn't do—is often the scariest thing of all.

Next Steps for Film Enthusiasts

To get the most out of your screening, compare the 1962 version with the 1991 remake back-to-back. Focus specifically on the character of Max Cady. While De Niro focuses on the "philosophy" and "rebirth" of the character, Mitchum focuses on the "animal." You will find that the 1962 version relies heavily on the tension of what might happen, whereas the 1991 version is about the inevitability of what is happening. Additionally, research the "Hays Code" restrictions of 1962 to see just how much the director and cast had to fight to get the film's darker themes onto the screen. This context makes the performances of the cast of the original Cape Fear even more impressive, as they had to convey "taboo" threats through subtext and atmosphere rather than explicit dialogue.