Sidney Lumet had a problem. He wanted to film Agatha Christie's most famous puzzle, but he knew the plot was basically a locked-room mystery where everyone just sits around talking. To make it work, he needed more than just actors. He needed icons. He needed the kind of star power that could make a train carriage feel like a royal court. When we talk about the cast of 1974 Orient Express, we aren't just talking about a movie lineup. We’re talking about a historic gathering of EGOT winners, Shakespearean legends, and old Hollywood royalty that will likely never be replicated.

Honestly, looking back from 2026, it’s wild to see how many "Greatest of All Time" contenders were crammed into those Pullman coaches.

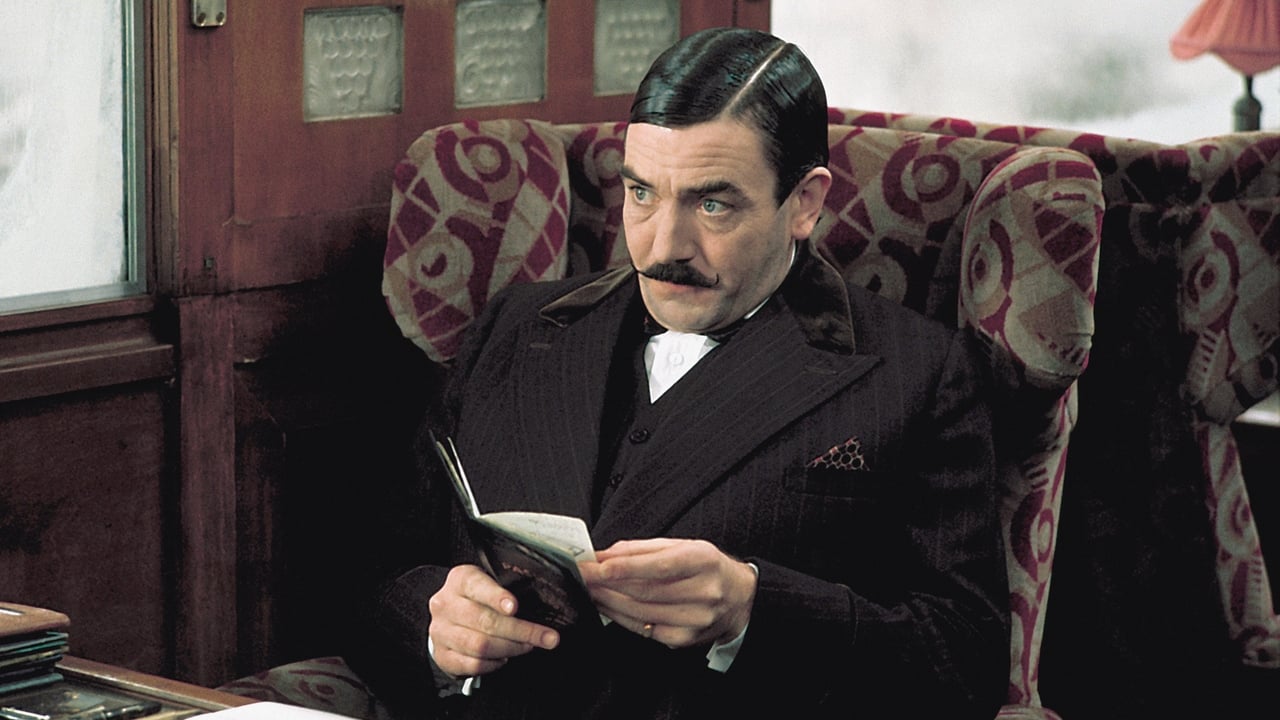

Albert Finney was only 38 when he took on Hercule Poirot. Think about that for a second. He was playing a man decades older, padded with pillows and hidden under a thick layer of greasepaint and a dye job that made his hair look like patent leather. He wasn’t the first choice—Lumet actually wanted Alec Guinness—but Finney brought a frantic, high-strung energy to the Belgian detective that felt dangerously close to a nervous breakdown. It worked.

The sheer gravity of the ensemble

Usually, movies have one or two "anchors." This film had a dozen.

You had Ingrid Bergman playing Greta Ohlsson, the "backward" missionary. Interestingly, Lumet initially wanted her for the role of Princess Dragomiroff. Bergman, showing the kind of instinct that wins Oscars, refused. She wanted the small, awkward role of the nurse. She had one long, five-minute interrogation scene filmed in a single take. She won her third Academy Award for it. Just five minutes of screen time. That is the level of efficiency we're dealing with here.

Then there’s Lauren Bacall. She played Mrs. Hubbard, the loud, abrasive American who doesn't know when to stop talking. Bacall was basically playing a version of her own public persona but dialed up to eleven. She provided the friction. Without her, the movie would have been too polite, too British, too quiet.

🔗 Read more: Jack Blocker American Idol Journey: What Most People Get Wrong

A literal Who's Who of 20th-century acting

- Sean Connery was fresh off his struggle to escape the shadow of James Bond. Playing Colonel Arbuthnot gave him the chance to be stiff, upright, and intensely Scottish in a way that felt grounded.

- Vanessa Redgrave played Mary Debenham with a sort of ethereal, cool detachment that perfectly balanced Connery’s intensity.

- Wendy Hiller as Princess Dragomiroff looked like a fragile bird of prey made of ancient lace and iron.

- John Gielgud played the valet, Beddoes. Imagine having one of the greatest stage actors in the history of the English language playing a man who spends half the movie ironed into the background.

It's sorta ridiculous.

Why this specific lineup worked where others failed

Since 1974, we’ve had Kenneth Branagh’s star-studded versions and the Peter Ustinov era. They’re fine. But they often feel like "stunt casting." You see the celebrity first, then the character. In the cast of 1974 Orient Express, Lumet managed to subvert the fame of his stars.

The trick was the claustrophobia.

The set was built with movable walls, but it was still tiny. These actors were physically trapped together for weeks. Anthony Perkins, famous for Psycho, played Hector McQueen. He brought this twitchy, nervous energy that felt like a callback to Norman Bates, but refined for a high-society setting. He and Richard Widmark—playing the victim, Ratchett—created a palpable sense of dread before the first scream was even heard.

The production was a logistical nightmare. Because everyone was a massive star, the "above the title" billing was a headache. They ended up listing the stars in alphabetical order to avoid any ego bruising. That’s why the opening credits feel like a march of the titans.

💡 You might also like: Why American Beauty by the Grateful Dead is Still the Gold Standard of Americana

The forgotten performances

Most people remember Bergman and Finney. But look at Michael York as Count Andrenyi and Jacqueline Bisset as the Countess. They brought a tragic, youthful glamour to a cast that was otherwise dominated by the "old guard." They represented the beauty that the central crime had destroyed.

And then there’s Martin Balsam as Bianchi. He’s the audience surrogate. He’s the one jumping to conclusions, getting excited, and letting Poirot (and us) know just how impossible the case is. His chemistry with Finney is the heartbeat of the film’s pacing.

The Agatha Christie seal of approval

Agatha Christie was notoriously unhappy with adaptations of her work. She generally hated them. She thought they missed the point or made Poirot look silly.

However, she attended the premiere of the 1974 film. It was her final public appearance. She reportedly liked it, though she did have one specific complaint about Finney. She thought his mustache wasn't quite grand enough. If the only thing the Queen of Crime can find fault with is the length of a mustache, you’ve probably made a masterpiece.

Technical mastery behind the faces

You can’t talk about the cast without the lighting. Geoffrey Unsworth, the cinematographer, used heavy diffusion. He wanted the movie to look like a memory, or a dream. This softened the actors' features, making the veterans look timeless and the younger stars look like porcelain dolls.

📖 Related: Why October London Make Me Wanna Is the Soul Revival We Actually Needed

The costumes by Tony Walton were equally vital. They weren't just "period dress." They were armor. Every silk scarf and heavy wool overcoat told you about the social standing of the passenger. When you see the cast lined up in the dining car for the final reveal, the visual composition is like a Renaissance painting.

How to truly appreciate the 1974 ensemble today

If you're going to revisit this classic, don't just watch it for the "whodunnit." Most people know the ending by now. Watch it for the "how-they-do-it."

Pay attention to the background of shots. Watch how Sean Connery reacts when he’s not the focus of the scene. Notice the way Wendy Hiller uses her hands. There is a density of craft here that modern CGI-heavy blockbusters can't replicate. It’s a masterclass in ensemble acting where no one is trying to "steal" the movie, yet everyone is playing at 100%.

To get the most out of a rewatch, try these steps:

- Focus on the interrogation sequence: Watch how Finney changes his posture and accent slightly depending on who he is talking to. He’s a chameleon.

- Look for the "silent" acting: The scenes where the train is stuck in the snow are great for observing how the actors convey boredom and rising panic without dialogue.

- Compare the 1974 version to the 2017 remake: Notice the difference in "weight." The 1974 cast feels like they belong in that era; the modern versions often feel like contemporary actors playing dress-up.

- Check out the "Making Of" documentaries: There are several retrospectives that detail the legendary "Orient Express" dinner parties the cast had during filming. It explains why their chemistry feels so lived-in.

The 1974 film remains the definitive version of this story because it understood that the Orient Express wasn't just a train. It was a stage. And on that stage, you needed the greatest players in the world. They delivered. Case closed.