I still remember the smell of the old library copy of Mossflower. It was that distinct mix of vanilla-scented decaying paper and something slightly earthy. Fitting, honestly. When you crack open any book in the Brian Jacques Redwall series, you aren’t just reading a story about mice in habits; you’re stepping into a sensory overload.

Jacques didn’t just write books. He built a world out of gravel, honey, and sharpened steel.

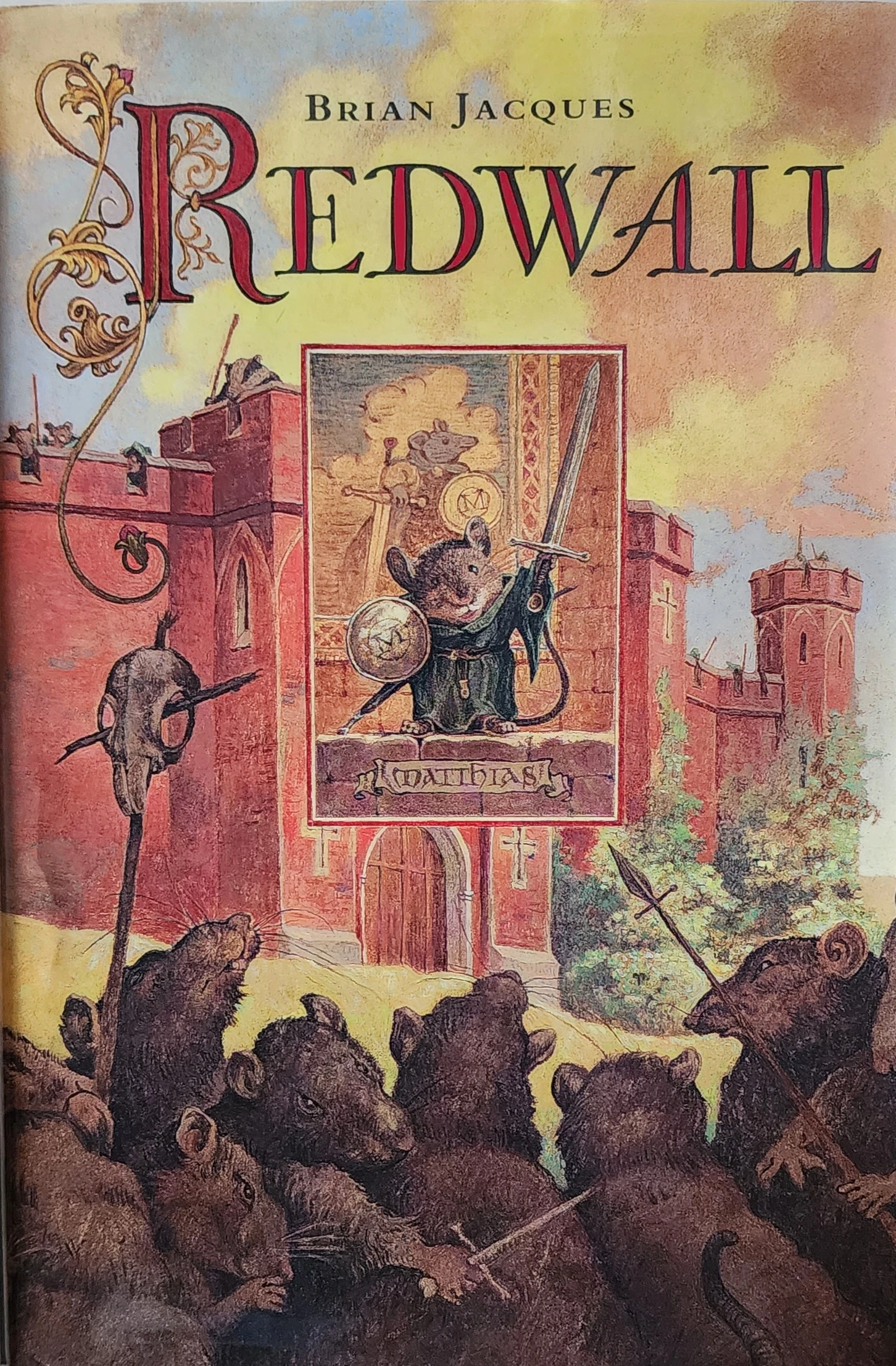

Most people think of Redwall as "Redwall," the first book published back in 1986. But the series is a sprawling, 22-book behemoth that spans centuries of fictional history. It’s weirdly violent for kids' fiction. It’s also incredibly hungry. If you’ve ever felt a sudden, inexplicable craving for deeper-than-ever turnip'n'tater beetroot pie or strawberry cordial, you can blame Brian. He wrote those descriptions for children at the Royal School for the Blind in Liverpool, using words to paint the textures and tastes they couldn't see. That’s why the prose feels so thick.

It’s tactile.

The unexpected grit of Mossflower Country

Let’s get one thing straight: these aren't cute stories. Sure, the protagonists are mice, squirrels, and otters. But the stakes are life and death. Always. Jacques didn't shy away from the brutality of nature or the cold reality of a siege. In the Brian Jacques Redwall series, characters you love die. They die in battle, they die of old age, and sometimes they die in ways that feel deeply unfair.

Take Mariel of Redwall. You have a young mousemaid washing up on a shore with nothing but a knotted rope—the "Gullwhacker"—and a burning desire for revenge against a pirate rat named Gabool the Wild. It’s a revenge epic. Or look at Taggerung, which tackles themes of nature versus nurture as an otter is raised by a clan of vermin assassins.

💡 You might also like: Songs by Tyler Childers: What Most People Get Wrong

The villains are legitimately terrifying. Cluny the Scourge isn't just a rat; he’s a psychological nightmare with a detachable tail-spike. Slagar the Cruel wears a silk mask because his face was mangled by an adder. These aren't "misunderstood" villains. They are avatars of greed and chaos. Jacques understood that for heroism to mean anything, the darkness has to be genuinely dark.

Why the feast scenes actually matter

Critics sometimes poked fun at Jacques for the endless pages dedicated to food. He’d spend three paragraphs describing a candied chestnut and then two sentences on a skirmish. But that was the point. The Abbey of Redwall represents peace, community, and the fruits of honest labor. The food is the reward for the struggle.

In a world where a wildcat or a ferret might burn your home down tomorrow, a bowl of hot soup and a piece of crusty bread is a radical act of defiance.

It’s about the "Long Patrol" hares—those gloriously posh, perpetually hungry soldiers of Salamandastron—who live on the edge of the world to protect others. They joke about scones while facing down thousands of enemies. It’s a very British sort of stoicism. Jacques was a merchant seaman, a lighthouse keeper, and a truck driver before he was a world-famous author. You can feel that blue-collar work ethic in every chapter. He respected the baker as much as the warrior.

The timeline is a bit of a mess (and that’s okay)

If you’re trying to read the Brian Jacques Redwall series in chronological order, good luck. You'll be jumping all over the place.

📖 Related: Questions From Black Card Revoked: The Culture Test That Might Just Get You Roasted

Lord Brocktree takes place centuries before the original Redwall, while Eulalia! or The Rogue Crew sit much later in the mythos. Most fans suggest reading in publication order first. Why? Because the legend of Martin the Warrior needs to grow. In the first book, Martin is a semi-mythical figure, a ghost in the rafters. As the series progresses, Jacques goes back to show us the flesh-and-blood mouse who actually held the sword.

Seeing the "origin story" in Mossflower hits harder when you already know the Abbey exists because of his sacrifice. It’s world-building through archaeology. You see the ruins before you see the fortress.

What most people get wrong about the "Formula"

Critics often say every Redwall book is the same.

- A threat emerges.

- A young, unlikely hero finds a quest.

- There’s a riddle to solve.

- A massive battle happens.

- Everyone eats.

While that structure exists, it ignores the nuance of the later books. Jacques started playing with the tropes. In The Outcast of Redwall, he explored whether a ferret—traditionally "evil" in this world—could be raised to be good. The answer was complicated and, honestly, pretty depressing. It challenged the biological determinism that some readers found problematic in the earlier entries.

Then you have the Badger Lords. These are the tanks of the Redwall world. Characters like Sunflash the Gold or Boar the Fighter bring a different scale to the conflict. When a Badger Lord enters "Bloodwrath," the book stops being a whimsical animal tale and turns into a berserker epic. The shift in tone is jarring in the best way possible.

👉 See also: The Reality of Sex Movies From Africa: Censorship, Nollywood, and the Digital Underground

The legacy of the tapestry

The Abbey itself is the main character. It’s a place of sanctuary. In a genre often obsessed with "chosen ones" and royal bloodlines, Redwall is about a collective. The Abbot or Abbess isn't a king or queen; they are healers and administrators. The sword of Martin the Warrior doesn't have magical powers—it’s just a symbol. The strength comes from the person holding it and the community behind them.

This resonates because it feels attainable. Most of us aren't 7-foot-tall warriors. But we can all be the mouse who stands up when a bully shows up at the door.

Jacques passed away in 2011, but the series hasn't faded. With talk of Netflix adaptations and a constant stream of new readers discovering the paperbacks in middle school libraries, the Abbey’s bells are still ringing. It’s a rare feat to create a world that feels both dangerous and incredibly safe at the same time.

How to dive back into Mossflower today

If you’re looking to revisit the Brian Jacques Redwall series or introduce it to someone else, don't just start at page one. Immerse yourself in the specific "vibe" that made these books legendary.

- Start with Mossflower or Redwall: These are the pillars. Mossflower is arguably the better-written book, acting as a prequel that establishes the entire lore of the woods.

- Track the Riddles: Jacques loved wordplay. If you’re reading with a kid, try to solve the poems and anagrams before the characters do. It was his way of making the reader feel like a part of the Abbey’s history.

- The Audiobook Experience: Brian Jacques narrated many of the audiobooks himself, alongside a full cast. Hearing his thick Liverpool accent bring the characters to life is the definitive way to experience the stories. He voiced the moles with a West Country dialect that is just pure gold.

- Look for the Illustrated Versions: If you can find the editions illustrated by Gary Chalk or David Elliot, grab them. The pen-and-ink style captures the "medieval" feel far better than any modern digital cover ever could.

- Cook the Food: There are fan-made Redwall cookbooks (and an official one) floating around. Making a batch of "deeper-than-ever" pie is a legitimate way to connect with the series. Just maybe skip the candied meadow-worms.

The magic of these books isn't in the "epicness" of the battles. It's in the small moments—the lanterns swinging in the wind, the sound of a stream, and the idea that even the smallest creature can hold back the tide of darkness if they have enough heart (and a good meal).