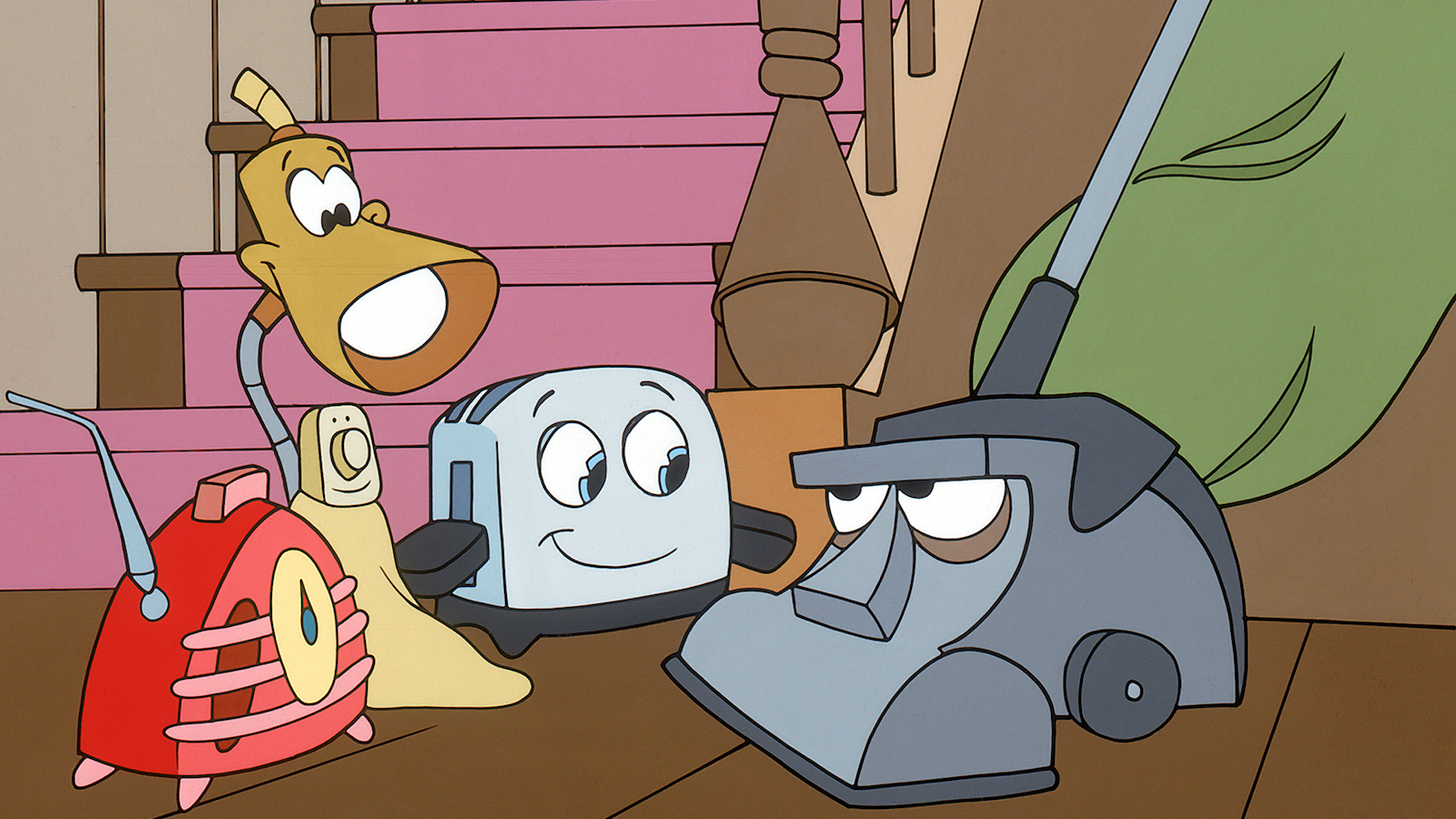

You probably remember the singing appliances. Maybe you remember the catchy "City of Light" tune or the way the Blanky looked like it desperately needed a wash. But if you sit down and actually rewatch The Brave Little Toaster movies, you’ll realize something pretty quickly. These aren't just cute Disney-adjacent flicks. They’re actually kind of terrifying. Honestly, they’re existential horror movies disguised as children's animation.

The 1987 original, produced by Hyperion Pictures, wasn't even a Disney movie at first, though Disney eventually handled the home video distribution. That distinction matters. Because it wasn't a "pure" Disney product, it was allowed to go to some incredibly dark places. We’re talking about "Worthless," the song where cars literally sing about their own deaths while being crushed into scrap metal. It’s heavy stuff.

When people talk about this franchise, they usually focus on the first film. But there’s a whole trilogy here. You’ve got The Brave Little Toaster to the Rescue and The Brave Little Toaster Goes to Mars. If the first movie was about the fear of being abandoned, the sequels tackled everything from animal testing to the cold vacuum of space. It’s a wild ride that most 90s kids still haven't fully processed.

The Weird History Behind the Original Classic

Before it was a movie, The Brave Little Toaster was a novella by Thomas M. Disch. Disch was a serious science fiction writer, and that DNA is all over the film. He didn't write "kid stuff." He wrote about the human condition. When Jerry Rees directed the adaptation, he kept that edge. It’s why the vacuum, Kirby, has a near-mental breakdown. It’s why the AC unit literally explodes out of pure, unadulterated rage.

The animation team was a powerhouse of future talent. Did you know Joe Ranft, who went on to be a massive creative force at Pixar, worked on this? Or that it was one of the first films to really experiment with computer-generated imagery for the movement of the toaster’s reflections? It was ground-breaking.

But let's talk about the "clown" scene. You know the one. The Toaster has a nightmare where a fire-breathing clown dressed as a fireman whispers "run" before trying to drown him. It’s a core memory for an entire generation of traumatized toddlers. That scene alone proves the creators weren't interested in making a safe, generic cartoon. They wanted to explore the anxiety of being obsolete.

The budget was tight. Really tight. Around $2.3 million, which even in the 80s was peanuts for a feature-length animation. Yet, the voice acting is top-tier. Phil Hartman—the legend—voiced the Air Conditioner and the Hanging Lamp. Jon Lovitz brought a frantic, insecure energy to the Radio. These weren't just "funny voices." They were characters struggling with the fact that their "Master" had grown up and left them behind.

Why the Sequels Feel So Different

If you watched the sequels back-to-back with the original, you probably noticed a shift. The animation looks thinner. The colors are brighter. That’s because To the Rescue and Goes to Mars were produced simultaneously in the late 90s, almost a decade after the first one. They were direct-to-video projects.

👉 See also: Questions From Black Card Revoked: The Culture Test That Might Just Get You Roasted

To the Rescue takes a weird turn into social commentary. The appliances are now living in a veterinary clinic, and the plot revolves around a computer virus and a ring of people selling lab animals for experiments. It's surprisingly gritty for a movie featuring a talking toaster. We see the appliances trying to save a bunch of animals—including a rat named Ratso—from a grim fate. It lacks the poetic melancholy of the first movie but replaces it with a frantic, "save the day" energy.

Then things get truly bizarre.

In The Brave Little Toaster Goes to Mars, they... well, they go to Mars. The Master’s baby gets teleported to the red planet, and the appliances hitch a ride on a microwave and a bag of popcorn to go get him. It sounds like a fever dream. It basically is. But even here, the movie sneaks in some heavy themes. The "Great Supreme Commander" on Mars is a giant refrigerator who wants to invade Earth because he thinks humans are wasteful. It’s an environmentalist message wrapped in a space opera.

Interestingly, while Goes to Mars was released last, it was actually produced before To the Rescue. The release order got swapped, which creates some minor continuity hiccups if you’re looking closely. Most kids didn't care, but for the lore-obsessed, it’s a fun bit of trivia.

The "Worthless" Scene: A Deep Dive into Existential Dread

We have to talk about the junkyard. It is arguably the most famous sequence in the entire The Brave Little Toaster movies library. The song "Worthless" is a masterpiece of dark storytelling. Each car that goes into the crusher tells its life story in about four bars of music.

One car was a race car. One was a hearse. One was a "surfer wagon."

They aren't just machines; they are sentient beings who have accepted their own execution. They sing about how they "can't go on" and how they've reached the end of the road. It’s incredibly bleak. The imagery of the giant magnet lifting them to their doom is reminiscent of some of the darkest moments in cinema history.

✨ Don't miss: The Reality of Sex Movies From Africa: Censorship, Nollywood, and the Digital Underground

Why did this work? Because it tapped into a universal human fear: the fear of being replaced. In the 80s, the world was shifting. High-tech gadgets were replacing old-school machinery. The appliances in the movie represent the "old guard." They are analog in a digital world. When the Toaster and his friends reach the city and see the "Cutting Edge" appliances—the sleek, chrome, modern versions of themselves—they don't feel inspired. They feel threatened.

The "Cutting Edge" song is the perfect foil to "Worthless." It’s cold, synthesizer-heavy, and arrogant. It represents the soulless nature of consumerism. The movie is basically telling us that being "new" doesn't mean you're better; it just means you haven't been thrown away yet.

The Voice Cast and the Hartman Legacy

Phil Hartman’s contribution to these movies cannot be overstated. Before he was a Saturday Night Live icon or the voice of Lionel Hutz on The Simpsons, he was an AC unit having a mid-life crisis. Hartman had this incredible ability to make a character sound both pompous and incredibly fragile at the same time.

When the Air Conditioner gets angry at the other appliances for thinking the Master loves them, he’s not just being a jerk. He’s grieving. He’s bolted to the wall. He can’t leave. He’s stuck in a room, watching the world through a window he can’t reach. Hartman’s performance brings a layer of tragedy to a character that could have just been a one-dimensional villain.

Then you have Thurl Ravenscroft. You might not know the name, but you know the voice. He was the voice of Tony the Tiger ("They're G-r-reat!") and the singer of "You're a Mean One, Mr. Grinch." In The Brave Little Toaster, he voices Kirby, the grumpy old vacuum cleaner. Ravenscroft’s deep, rumbling bass gives Kirby a sense of history. He’s the anchor of the group, even if he’s constantly complaining about how much dust he has to eat.

Misconceptions and Forgotten Lore

A common misconception is that this is a Pixar movie. It isn't. However, the DNA is so similar that it’s easy to see why people get confused. John Lasseter, the co-founder of Pixar, actually pitched a 3D-animated version of The Brave Little Toaster to Disney back in the early 80s.

It didn't go well.

🔗 Read more: Alfonso Cuarón: Why the Harry Potter 3 Director Changed the Wizarding World Forever

Lasseter was pushing for computer animation, which was incredibly expensive and unproven at the time. Disney executives weren't convinced, and the tension over the project eventually led to Lasseter being fired from Disney. He then went to Lucasfilm’s computer division, which eventually became Pixar. So, in a weird way, the failure of the 3D Toaster project is what paved the way for Toy Story.

Another thing people forget: the movie was a massive hit at Sundance. It was the first animated film ever exhibited at the Sundance Film Festival. It even won the Special Jury Recognition for Animation. This wasn't just a "kids' cartoon"; it was an indie darling that critics took very seriously.

Technical Details You Probably Missed

The soundtrack, composed by David Newman, is actually quite sophisticated. Newman (part of the legendary Newman film-scoring dynasty) used a mix of orchestral arrangements and early electronic elements to mirror the "appliance" theme.

If you listen closely to the sound design, every appliance has a distinct mechanical "heartbeat."

- The Toaster: A light, metallic clink.

- The Lampy: A buzzing electrical hum.

- The Radio: Static and clicking knobs.

- The Blanket: Soft, muffled movements.

These details make the characters feel grounded. They aren't magical beings; they are mechanical objects that have somehow developed a soul. This "groundedness" is what makes the threats they face—like the storm in the woods or the magnet in the junkyard—feel so dangerous. A toaster shouldn't be outside. A toaster shouldn't be in a waterfall. The stakes are physical and immediate.

How to Revisit the Trilogy Today

If you’re looking to rewatch these, you might find the sequels a bit harder to track down than the original. The first movie is widely available on digital platforms and occasionally pops up on streaming services like Disney+. The sequels are often bundled together in DVD collections.

Is it worth watching the sequels? If you're a completionist or have kids, sure. To the Rescue has some heart, and Goes to Mars is so weird it’s almost worth it for the "spectacle" of seeing a toaster in a space helmet. But the 1987 original remains the gold standard. It’s a movie that respects its audience’s intelligence and doesn’t shy away from the fact that life can be scary, unfair, and exhausting.

The "Master" in the movie, Rob, eventually finds his appliances. He repairs them. He takes them to college. It’s a happy ending, but it’s a hard-earned one. The movie doesn't tell us that everything is perfect; it tells us that loyalty and friendship are what keep us from the scrap heap.

What You Can Do Now

- Check out the original novella: Thomas M. Disch’s The Brave Little Toaster is a short read but offers a much more cynical, satirical look at the story. It’s fascinating to see what the movie changed to make it more "palatable" for film.

- Watch the "Worthless" sequence on YouTube: If you don't have time for the whole movie, just revisit that one song. Watch it with adult eyes. Pay attention to the lyrics. It’s a masterclass in visual storytelling and tone.

- Look for the "Making Of" documentaries: There are some great behind-the-scenes clips of the voice actors recording their lines. Seeing Phil Hartman scream at a microphone as a grumpy air conditioner is a treat.

- Compare the animation styles: Watch five minutes of the first movie and five minutes of Goes to Mars. It’s a great way to see how the industry changed from high-effort theatrical animation to the direct-to-video boom of the late 90s.

- Introduce it to a new generation: If you have kids or niblings, show them the first one. It’s a great litmus test for their attention span and their ability to handle "spooky" themes. Just maybe skip the clown scene if they’re prone to nightmares.