If you walk into the Long Room at Trinity College Dublin, everyone is crowded around the Book of Kells. It’s the superstar. It’s flashy. But honestly? If you want to understand where Western art actually found its soul, you need to look at the Book of Durrow.

It’s smaller. It’s older. It’s weirder.

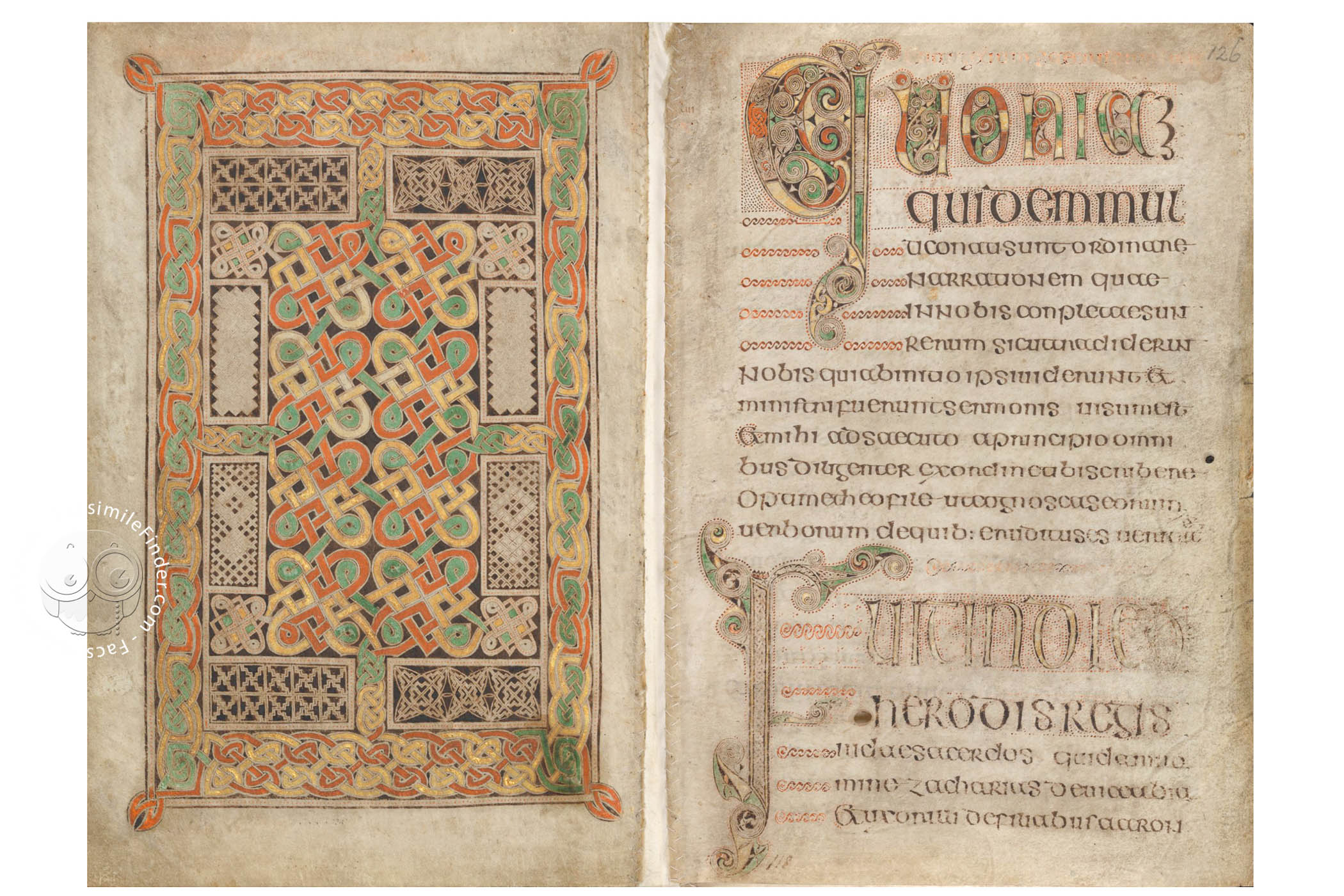

The Book of Durrow is basically the "indie prequel" to the blockbuster that is Kells. Created around 650–700 AD, this manuscript is the earliest fully decorated Insular Gospel book we have. While Kells is a maximalist explosion of color, Durrow is a masterclass in clean, geometric obsession. It’s the bridge between the late Roman world and the wild, knot-obsessed art of the Celts and Anglo-Saxons.

People argue about where it came from. Some say Iona in Scotland. Others swear by Northumbria in Northern England. But for centuries, its home was the monastery at Durrow in County Offaly, Ireland. It stayed there so long that locals eventually started thinking the book had literal magic powers.

The Book of Durrow and the "Holy Water" Myth

History is messy. Sometimes, it’s even a bit gross. By the 17th century, the Book of Durrow wasn't just viewed as a religious text; it was a veterinary tool.

I’m serious.

📖 Related: Charlie Gunn Lynnville Indiana: What Really Happened at the Family Restaurant

The MacGeoghegan family, who were the hereditary guardians of the book at the time, used to take the manuscript and dip it into troughs of water. They believed that if a cow was sick, drinking "book-infused" water would cure it. We know this because Henry Jones, a Scoutmaster General and later Bishop of Meath, mentioned it when he eventually took possession of the book. You can still see the water damage on some pages today. It’s a miracle the thing didn't just disintegrate into a pile of soggy vellum.

This isn't just a fun piece of trivia. It tells us something deep about how these objects were viewed. To the medieval and early modern mind, the Word of God wasn't just a set of instructions. It was a physical substance. It was power.

Why the "Man" of Matthew Looks Like a Lego Character

One of the first things you notice when looking at the Book of Durrow is the Evangelist symbols. In Christian tradition, the four Gospel writers are represented by a Man (Matthew), a Lion (Mark), a Calf (Luke), and an Eagle (John).

But look at the Man of Matthew.

He doesn't have arms. He’s basically a colorful, checkered rectangle with a head and two feet sticking out of the bottom. Scholars call this the "bell-shaped" figure. To a modern eye, it looks primitive, maybe even a bit funny. But look closer at the pattern on his "cloak." It’s a sophisticated millefiori design, mimicking the high-end enamel work found in Anglo-Saxon metalwork, like the treasures found at Sutton Hoo.

👉 See also: Charcoal Gas Smoker Combo: Why Most Backyard Cooks Struggle to Choose

The artist wasn't bad at drawing people. They just didn't care about realism. They cared about pattern.

A Different Way of Seeing

In the 7th century, the Mediterranean world was obsessed with trying to make things look "real." But the monks in the North? They were into abstraction. They wanted to capture the essence of a thing through geometry.

- The Lion of Mark (who is actually positioned before the Gospel of John in this specific book, which is a whole other mystery) is covered in stylized red and green spots.

- The borders are filled with "interlace"—those complex, weaving ribbons that look like they have no beginning or end.

- The "Carpet Pages" are pure decoration, meant to prepare the reader’s mind for the sacred text that follows.

These Carpet Pages are a huge deal. They look incredibly similar to Coptic (Egyptian Christian) textiles and even Islamic prayer rugs. It shows that the monks in Ireland and Britain weren't isolated. They were part of a massive, global network of artistic exchange.

The Mystery of the "Wrong" Order

If you’re a Bible scholar, the Book of Durrow might give you a headache. In most Bibles, the order of the Evangelists is Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. Durrow follows the "Vulgate" text but uses the "Pre-Vulgate" or "Old Latin" arrangement for its symbols.

This means the symbols are all swapped around compared to what we’re used to. It’s one of the main reasons experts like Bernard Meehan or the late Françoise Henry spent decades debating exactly which monastery produced the book. If the symbols follow an older tradition, does that mean the book was made in a place that was stubborn about its history? Or was the artist just following a specific, rare model brought over from Italy or Spain?

✨ Don't miss: Celtic Knot Engagement Ring Explained: What Most People Get Wrong

We don't know. That’s the beauty of it.

The Material Reality of Vellum

Writing this book was an athletic feat. Vellum is made from calfskin. To make a book the size of the Book of Durrow, you need a lot of cows. Specifically, scholars estimate it took about 150-200 calfskins to produce the pages.

The ink wasn't just ink, either.

- Black came from iron gall or soot.

- Red came from red lead or cinnabar.

- Yellow came from orpiment (which is basically arsenic—don't lick the pages).

- Green was often made from verdigris (copper rust).

The monks were essentially chemists. They were mixing toxic minerals with egg whites and honey to make sure the Word of God would stay vibrant for a thousand years. It worked.

How to Experience the Book of Durrow Today

You don't just "read" the Book of Durrow. You study the rhythm of it. If you ever get the chance to see it in person at Trinity College, or even just look at the high-resolution scans provided by the library, pay attention to the diminuendo.

This is a specific artistic trick where the first letter of a page is massive, and the next few letters gradually get smaller until they reach the size of the regular text. It’s like a visual "fade-in." It’s designed to guide your eye and your soul into the scripture.

Actionable Ways to Engage with This History

- Visit Trinity College Dublin Virtually: The Library of Trinity College has digitized the entire manuscript. You can zoom in until you see the actual pores in the calfskin. It’s better than seeing it behind glass.

- Compare it to Sutton Hoo: Look up the "Great Gold Buckle" from the Sutton Hoo ship burial. Notice the snakes? Then look at the interlace in the Book of Durrow. The "pagan" metalwork and the "Christian" book are speaking the exact same visual language.

- Trace the Patterns: If you’re into art or mindfulness, try drawing a section of Durrow’s interlace. You’ll quickly realize that the monks had a level of focus and mathematical precision that is almost impossible to replicate with a pen and paper today. It’s a form of meditation.

- Read up on the Northumbrian-Irish Connection: To really get the nuance, check out the work of Michelle Brown. She’s one of the leading experts on how these cultures blended together to create "Insular" art.

The Book of Durrow isn't just a dusty relic. It’s the survivor of Viking raids, "holy water" drownings, and centuries of neglect. It represents the moment when the North of Europe stopped being "barbaric" in the eyes of the South and started creating the most sophisticated art in the known world. It’s small, it’s stained, and it’s perfect.