Hollywood used to be safe. You had the good guys in white hats, the bad guys in black hats, and a very clear line between who you were supposed to cheer for and who you wanted to see rot in jail. Then the Bonnie and Clyde 1967 movie came along and basically set the rulebook on fire. It didn't just break the rules; it laughed while doing it. Honestly, it's hard to explain to someone who wasn't there—or who hasn't studied film history—just how much of a middle finger this movie was to the status quo.

Arthur Penn, the director, took a script that had been passed around like a hot potato and turned it into a cultural earthquake. Warren Beatty wasn't just the star; he was the engine. He fought for this project when everyone else thought a movie about two serial killers who were also "kind of" in love was a terrible idea. And look, on paper, it sounds messy. It is messy. But that’s why it works.

The Blood, the Banter, and the End of the Hays Code

Before 1967, violence in movies was polite. Someone got shot, they clutched their chest, and they fell over without a drop of blood hitting their pristine shirt. The Bonnie and Clyde 1967 movie changed that in the first ten minutes. It’s violent. Not just "for its time," but actually, genuinely jarring.

The ending? It’s legendary.

If you haven’t seen it, the "ballet of death" where the duo is ambushed by a posse of lawmen involves more squibs and fake blood than most entire filmographies of that era combined. It lasted less than a minute but felt like an eternity. Critics at the time, like Joe Morgenstern from Newsweek, initially hated it. He called it a "stinking shot of red ink." But then something weird happened. He went back, watched it again with a younger audience, and realized he was wrong. He actually wrote a second review retracting his first one. That almost never happens in the world of professional criticism.

What makes the movie stay with you isn't just the gore. It’s the tonal whiplash. One second you’re watching a slapstick chase scene with banjo music (the iconic "Foggy Mountain Breakdown"), and the next, someone is getting their face blown off. It’s uncomfortable. It makes you feel like a voyeur. You’re laughing at these two idiots playing with guns, and then you’re hit with the reality that they are, you know, actually killing people.

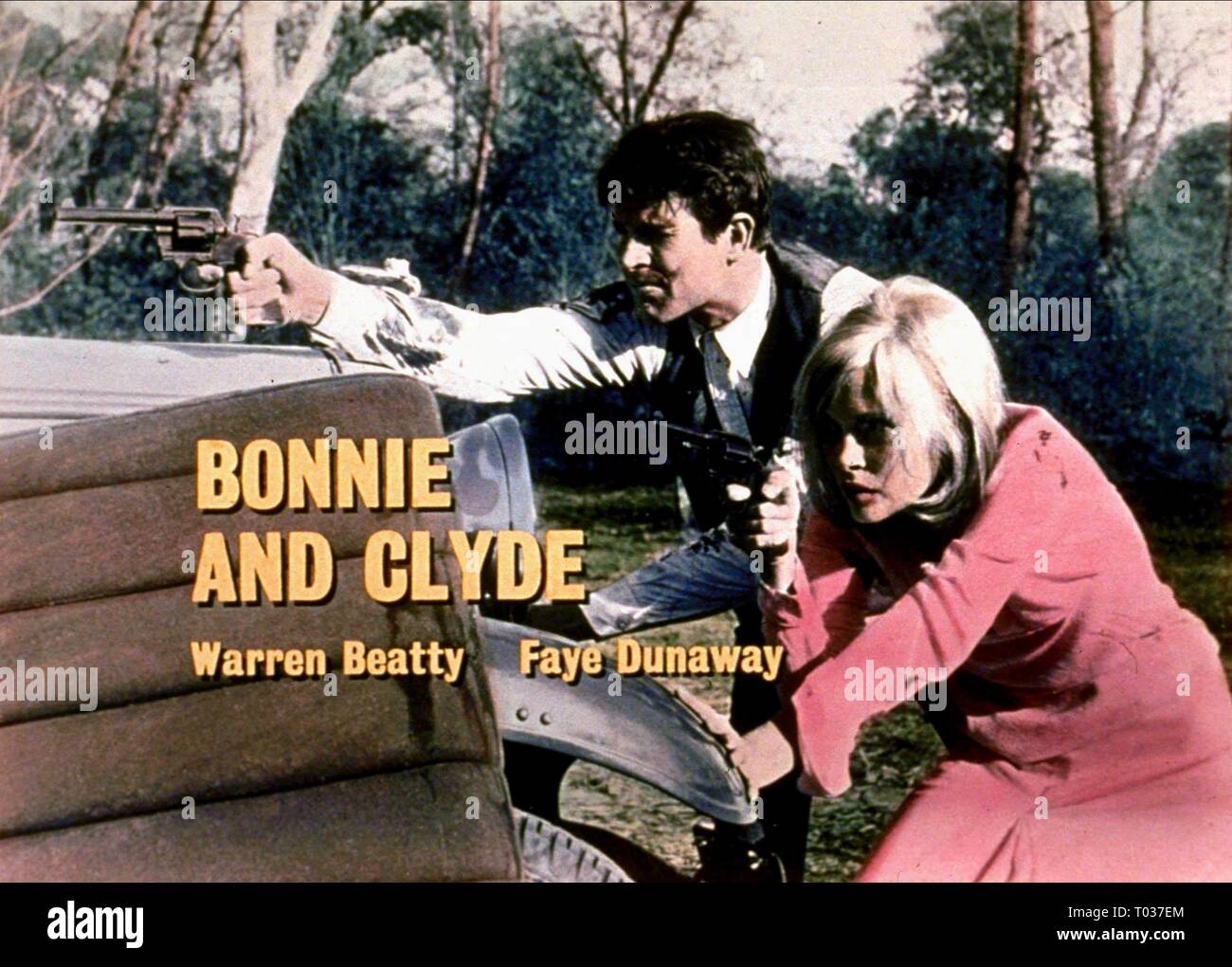

Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway: Anti-Heroes We Didn't Know We Wanted

Let’s talk about the casting because it’s basically perfect. Faye Dunaway as Bonnie Parker brought this weird, jittery, sexual frustration to the screen that was totally new. She wasn’t just a "gangster’s moll." She was bored. She was a waitress in a dead-end town who saw a guy stealing her mom’s car and thought, Yeah, that’s better than this. And Beatty. He played Clyde Barrow not as some alpha-male mastermind, but as a guy who was actually pretty insecure and, notably for the time, sexually impotent for much of the film.

📖 Related: Wrong Address: Why This Nigerian Drama Is Still Sparking Conversations

That was a huge risk.

Think about it: the biggest male star in Hollywood playing a character who couldn't perform? It humanized him in a way that made the violence feel even more tragic and pathetic. They weren't legends. They were just kids in over their heads.

The Reality vs. The Screenplay

Look, if you’re looking for a 100% accurate historical documentary, the Bonnie and Clyde 1967 movie is going to annoy you. David Newman and Robert Benton, the writers, took some massive liberties.

For starters, the real C.W. Moss was actually a composite of several people, mainly W.D. Jones and Henry Methvin. The real Frank Hamer—the Texas Ranger who hunted them down—wasn't some humiliated buffoon who got captured and spat on by the duo. In real life, Hamer was a legendary, highly competent lawman who never even met them until the day he helped put 167 bullets into their car.

Hamer’s widow actually sued the filmmakers for defamation because of how he was portrayed. She won an out-of-court settlement. So, if you're watching this for a history lesson, take it with a grain of salt. The movie is about the feeling of the Great Depression and the birth of the counterculture, not a chronological record of the Barrow Gang’s crimes.

Why It Still Matters in 2026

You might wonder why we're still talking about a movie from nearly sixty years ago. It’s because it paved the way for everything we love now. Without Bonnie and Clyde, you don't get The Godfather. You don't get Pulp Fiction. You don't get the "New Hollywood" era of the 70s where directors like Scorsese and Coppola were allowed to be gritty and weird.

👉 See also: Who was the voice of Yoda? The real story behind the Jedi Master

Basically, it broke the seal. It proved that audiences were smart enough to handle moral ambiguity. You could like a character who did bad things. You could feel bad for the "villain." That was a revolutionary concept for a mainstream American audience in the late sixties.

A Style That Refused to Die

Beyond the bullets, the movie's influence on fashion was insane. After the movie came out, everyone wanted to look like Faye Dunaway. The berets, the silk scarves, the midi-skirts—it killed the mini-skirt trend almost overnight. Theadora Van Runkle, the costume designer, created a look that felt vintage but also incredibly "mod" and current for 1967.

It wasn't just a movie; it was a vibe.

Even today, you see "Bonnie and Clyde" style editorials in Vogue or Harper’s Bazaar. It gave the Depression era a glamour it definitely didn't have in reality. In real life, Bonnie and Clyde were mostly dirty, tired, and sleeping in stolen cars. In the movie, they looked like rock stars on a road trip.

Breaking Down the Supporting Cast

We can't ignore Gene Hackman. He played Buck Barrow, Clyde's brother, and he was incredible. It was one of his breakout roles. He brought this loud, boisterous, "everything's-a-joke" energy that made the eventual tragedy of his character hit way harder.

And Estelle Parsons? She won an Oscar for playing Blanche Barrow. Some people find her screaming annoying—and she does scream a lot—but it captures the sheer terror of being a normal person caught in a whirlwind of crime. She didn't want to be an outlaw; she just wanted her husband to be okay. Her performance provides the grounded, terrifying reality that Bonnie and Clyde are trying to outrun.

✨ Don't miss: Not the Nine O'Clock News: Why the Satirical Giant Still Matters

The Cultural Context of 1967

You have to remember what was happening in America when this was released. The Vietnam War was televised every night. The civil rights movement was at a boiling point. The "youth" were angry, disillusioned, and tired of the establishment telling them what to do.

The Bonnie and Clyde 1967 movie tapped into that anger.

When Clyde says, "We rob banks," it wasn't just a statement of fact. To an audience in 1967, it felt like an anti-establishment anthem. Banks were the enemy. The government was the enemy. Even though the real Bonnie and Clyde were mostly robbing small grocery stores and gas stations—often hurting poor people—the movie reimagined them as folk heroes fighting a corrupt system.

It’s a bit of a lie, sure. But it’s a powerful one.

How to Appreciate the Film Today

If you're going to watch it (or re-watch it), don't just look at the screen. Listen to it. The sound design was revolutionary. The way the gunshots sound—loud, sharp, and echoing—was a deliberate choice to make the violence feel "present."

- Watch the editing. Dede Allen, the editor, used "jump cuts" and frantic pacing that felt more like French New Wave cinema than a standard Hollywood flick.

- Look at the locations. They filmed on location in Texas, often in the actual towns where the Barrow gang operated. It gives the film a dusty, authentic texture that you just can't get on a studio backlot.

- Notice the silence. Some of the most powerful moments have no music at all. Just the sound of wind or the engine of a Ford V8.

Moving Forward with Film History

The Bonnie and Clyde 1967 movie is more than just a crime flick. It’s a bridge between the old world and the new. If you want to dive deeper into how this movie changed the world, your next step is to look into the "New Hollywood" movement. Check out Easy Rider or The Graduate, which were released around the same time and share that same DNA of rebellion.

Honestly, the best thing you can do is find a high-definition 4K restoration. The colors—the burnt oranges and dusty yellows of the American South—are gorgeous. It doesn't feel like an "old movie." It feels like something that could have been made yesterday, and that’s probably the highest praise you can give any piece of art.

If you're interested in the "true" story, read Go Down Together by Jeff Guinn. It’s widely considered the most accurate account of the real Barrow gang, and it’ll show you exactly where the 1967 movie chose myth over reality. Comparing the two is a fascinating exercise in how Hollywood builds legends.