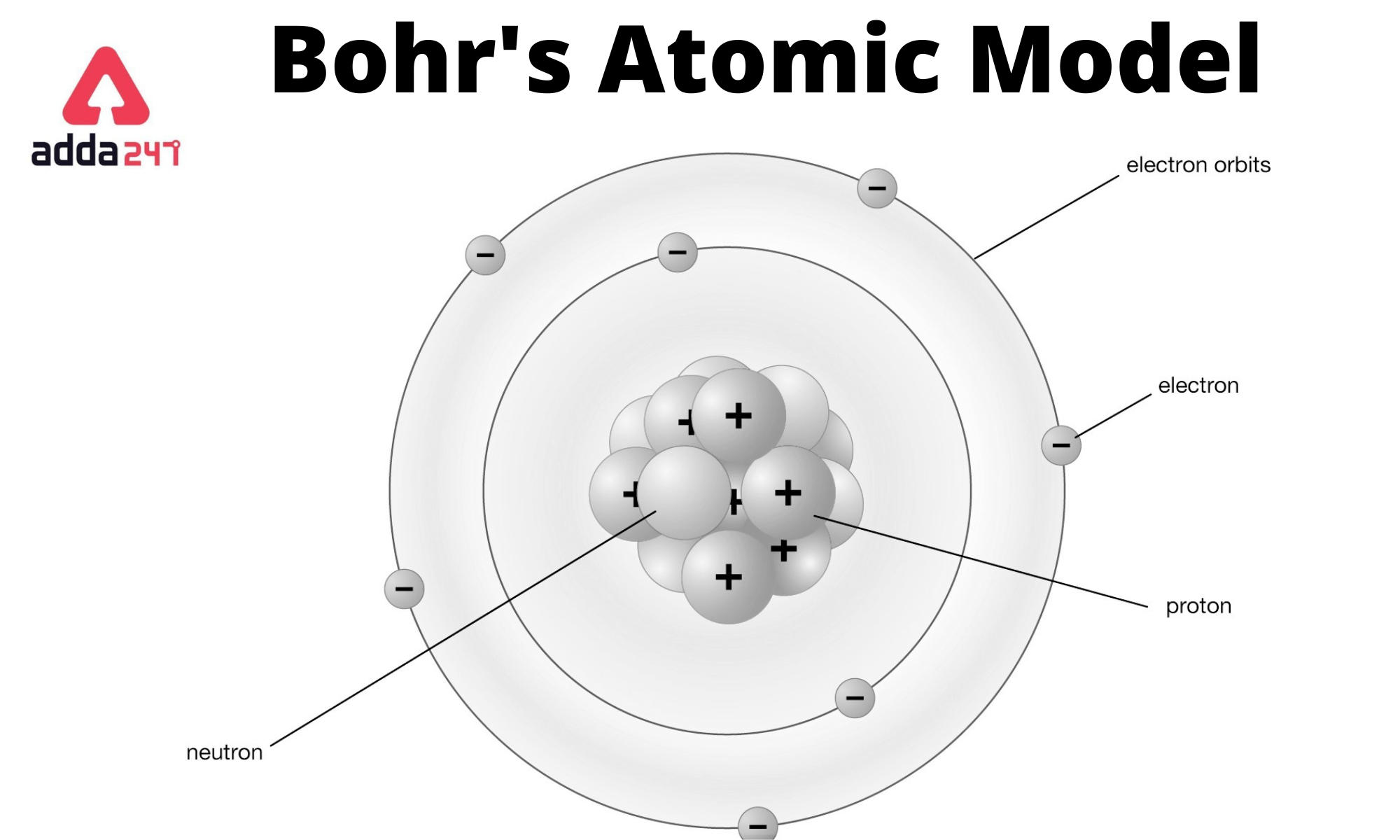

Think back to your middle school science classroom. You probably remember a poster on the wall showing an atom that looked like a tiny solar system. There’s a clump of red and blue balls in the middle, with little electrons zipping around in perfect circles like planets orbiting a sun. That image is the Bohr atomic model, and honestly, it’s one of the most successful "wrong" ideas in the history of science.

It’s been over a century since Niels Bohr sat down in 1913 to figure out why atoms don't just spontaneously collapse. Before he came along, the scientific community was in a bit of a crisis. If you followed the classical physics of the time, an atom shouldn't even exist. Electrons are negatively charged, and the nucleus is positive. They should just spiral inward and go kaboom. But they don't. Bohr’s big "aha!" moment changed everything, even if we’ve since moved on to even weirder quantum mechanics.

The Problem Bohr Had to Solve

Before we get into what the Bohr atomic model actually is, we have to look at the mess Niels Bohr inherited. Ernest Rutherford had already proven that atoms have a dense, positive nucleus. That was a huge deal. But there was a massive flaw. According to Maxwell’s electromagnetism, a moving charged particle (like an electron) should constantly lose energy. If it loses energy, it slows down. If it slows down, the nucleus sucks it in.

The universe should have lasted about a nanosecond. It didn't.

Bohr was a young Danish physicist working under Rutherford, and he decided to do something radical. He basically said, "What if the old rules of physics just don't apply at the atomic level?" He took Max Planck’s brand-new idea of "quanta"—the notion that energy comes in specific chunks rather than a smooth stream—and applied it to the atom. It was a gamble that fundamentally shifted how we view reality.

How the Bohr Atomic Model Works

Bohr’s theory is built on a few core pillars that seem simple now but were revolutionary then. First, he proposed that electrons orbit the nucleus in very specific paths. These aren't just random orbits; they are fixed "stationary states."

Each orbit has a specific energy level. The one closest to the nucleus has the lowest energy, and they get higher as you move out. Bohr called these "shells" or "n levels." This is why you see $n=1, n=2, n=3$ in textbooks. An electron is allowed to be in a shell, but it is strictly forbidden from being in the space between the shells.

Think of it like a ladder. You can stand on the first rung or the second rung. You can’t stand in the empty air between them.

The Quantum Leap

This is where things get trippy. Bohr explained how light is made. When an atom gets hit with energy—maybe from heat or electricity—an electron can jump from a lower shell to a higher one. This is an "excited state." But electrons are like us on a Sunday afternoon; they want to be at the lowest energy level possible.

When the electron falls back down to its original shell, it has to get rid of that extra energy. It spits out a photon, a tiny packet of light. The color of that light depends exactly on how far the electron fell. This perfectly explained the "emission spectra" of hydrogen—those weird colored lines you see when you look at burning gas through a prism.

Why Bohr Was Actually Wrong (But We Still Use It)

If you talk to a modern quantum chemist, they might roll their eyes a bit at the Bohr atomic model. Why? Because it’s not entirely accurate. It works beautifully for Hydrogen because Hydrogen only has one electron. Once you start adding more electrons (like in Helium or Oxygen), the math starts to fall apart.

Bohr’s model assumes we know exactly where an electron is and how fast it’s going. Werner Heisenberg later came along and proved that’s impossible with his Uncertainty Principle. Electrons aren't little billiard balls on tracks. They are more like "clouds" of probability.

Also, Bohr couldn't explain why some spectral lines are brighter than others or why they split when you put them in a magnetic field (the Zeeman effect).

👉 See also: Another Word for Luddite: Why We Keep Getting This Term Wrong

Despite these flaws, we teach Bohr's model first. Why? Because it introduces the concept of energy quantization without making your brain melt with complex wave functions. It’s a bridge. It takes us from the "everything is a solid object" world of Newton to the "everything is a wave" world of Schrödinger. Without Bohr, we wouldn't have lasers, transistors, or the MRI machines in our hospitals.

Practical Impact of Bohr’s Discovery

It’s easy to dismiss this as old-school textbook fluff, but Bohr’s insights are baked into the technology you’re using to read this.

- LED Lighting: The specific colors in your phone screen are created by electrons jumping between energy levels, just like Bohr described.

- Chemistry Bonding: While the "shells" are more complex (s, p, d, f orbitals), the idea that the outermost electrons dictate how atoms stick together comes directly from the Bohr lineage.

- Spectroscopy: Astronomers use Bohr’s logic to figure out what stars are made of. By looking at the light coming from a star millions of light-years away, they can see the "fingerprints" of electrons jumping in oxygen or iron atoms.

Moving Beyond the Solar System Model

Eventually, the Bohr atomic model gave way to the Quantum Mechanical Model. This newer version treats electrons as "standing waves." Instead of circular orbits, we have "orbitals"—weirdly shaped zones like dumbbells or spheres where an electron is likely to be.

But here is the thing: Bohr knew his model was a placeholder. He was a pragmatist. He famously said, "Everything we call real is made of things that cannot be regarded as real." He knew the universe was weirder than his little circles.

Actionable Takeaways for Science Students and Tech Enthusiasts

Understanding the atom isn't just for passing a chemistry quiz. It's the foundation of modern material science. If you want to dive deeper into how this stuff actually works in the real world, here is how to apply this knowledge:

1. Visualize the shells, but don't take them literally. When you look at a Periodic Table, remember that the rows (periods) actually correspond to the number of electron shells an atom has. That’s why elements in the same column behave similarly—they have the same number of electrons in their "Bohr-style" outer ring.

2. Explore the "Photoelectric Effect."

If you’re interested in solar energy, look up how Einstein and Bohr’s ideas overlap here. Solar panels work because light hits an atom and knocks an electron out of its shell. It’s the Bohr model in reverse.

3. Use the right tool for the job.

If you are doing basic chemistry or explaining how a lightbulb works, the Bohr model is your best friend. It’s clear and intuitive. If you are getting into semiconductor manufacturing or nanotechnology, you’ll need to put Bohr away and pick up the Schrödinger equation.

The Bohr atomic model remains one of the most elegant simplifications in science. It took the chaotic, invisible world of the very small and gave us a map we could actually understand. Even if the map isn't the territory, it’s the reason we found our way to the modern age.

👉 See also: Why the WAVE 3 Weather App is Still the Local Gold Standard

Investigate the emission spectra of different elements using a simple diffraction grating; it’s the quickest way to see Bohr’s energy levels with your own eyes. Check out the work of Arnold Sommerfeld if you want to see how scientists tried to "fix" Bohr's model by adding elliptical orbits before quantum mechanics took over entirely.