Paul Schrader was angry. He was coming off the massive success of writing Taxi Driver, but he wanted to direct, and he wanted to talk about the gears that grind people down. He ended up giving us the blue collar 1978 movie simply titled Blue Collar. It wasn't just a movie about a heist. Honestly, it was a autopsy of the American Dream performed on a cold factory floor in Detroit.

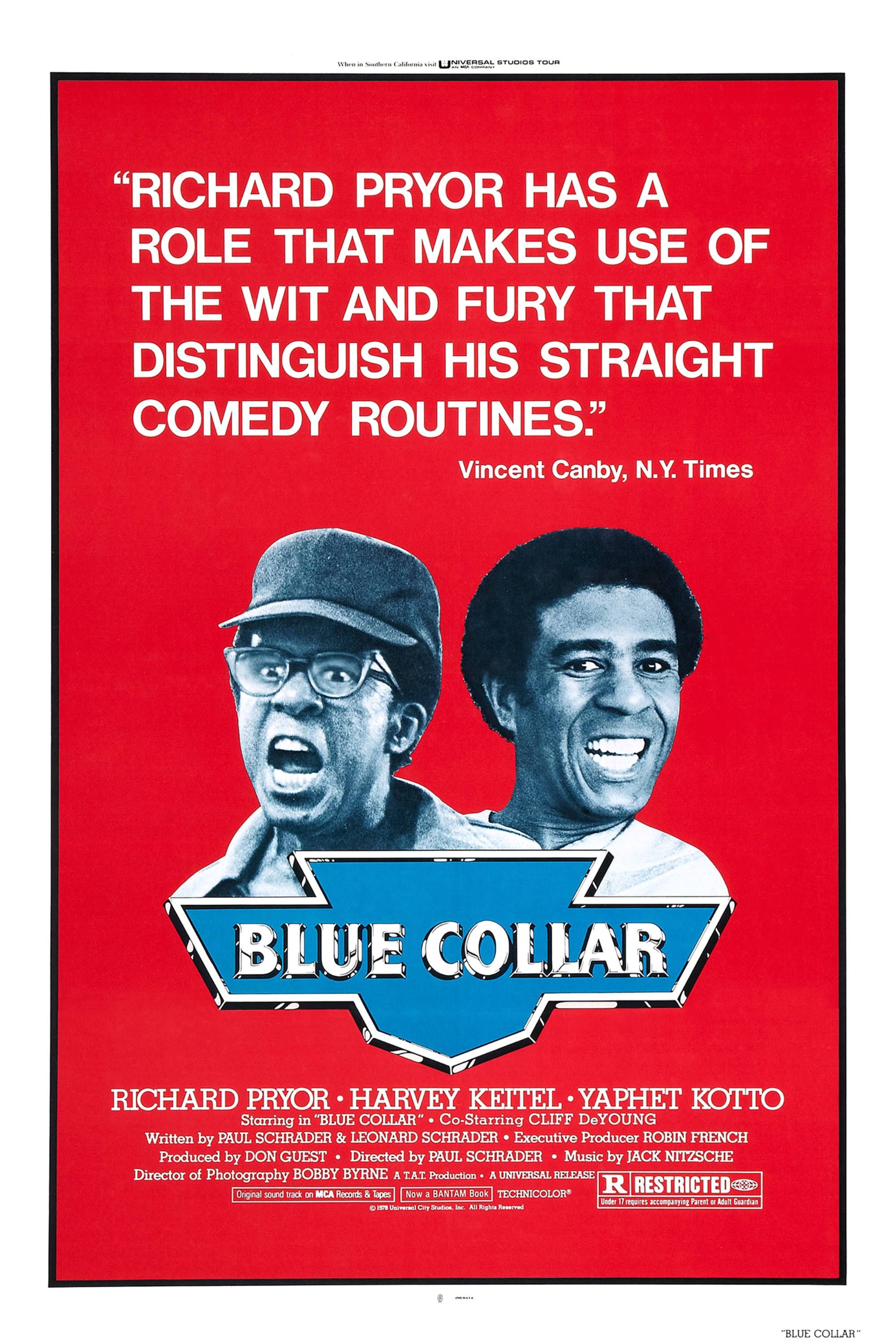

If you haven't seen it, the plot sounds like a standard crime flick. Three guys—Zeke (Richard Pryor), Jerry (Harvey Keitel), and Smokey (Yaphet Kotto)—work on an auto assembly line. They’re broke. They’re tired. They decide to rob their own union’s safe. But what they find isn't a mountain of cash; it's a paper trail of corruption that proves their "protectors" are just as predatory as the bosses.

It's a masterpiece. It's also a miracle it got finished, considering the lead actors supposedly hated each other so much that production was a literal war zone.

The Chaos Behind the Camera

You can't talk about Blue Collar without talking about the tension. This wasn't a "happy set." Schrader has famously recounted how the three leads—Pryor, Keitel, and Kotto—clashed constantly. There are stories of physical altercations. Schrader reportedly had a nervous breakdown during filming because the atmosphere was so toxic.

Yet, that friction is exactly why the movie feels so electric. When you see Zeke, Jerry, and Smokey screaming at each other in a small kitchen, that isn't just "great acting." It’s real frustration bleeding through the lens. The movie captures a specific kind of claustrophobia. It’s the feeling of being trapped in a life where your paycheck is already spent before you receive it, and your only friends are the people drowning right next to you.

Most films about the working class try to be "inspiring." They give you a hero who stands up to the man and wins. Blue Collar doesn't care about your feelings. It shows how the system is designed to keep the working class fighting each other so they don't look up and see who’s actually holding the whip.

🔗 Read more: Mike Judge Presents: Tales from the Tour Bus Explained (Simply)

Why the Blue Collar 1978 Movie Still Hits Different

Look at the assembly line scenes. They were filmed at the Checkpoint Checker Plant in Kalamazoo, Michigan. It’s loud. It’s dirty. The cinematography by Bobby Byrne doesn't try to make the machinery look cool or "industrial chic." It looks like a monster that eats time and health.

The movie handles race in a way that feels decades ahead of its time, too. In 1978, seeing a Black man and a white man as genuine, equal friends—sharing beers, complaining about their wives, and planning a crime—wasn't the norm for Hollywood. But the film also shows how the union uses race as a tool.

The Strategy of Division

There is a haunting quote from Smokey late in the film that basically summarizes the entire thesis of the blue collar 1978 movie. He talks about how the company and the union "work together to keep the guys at each other's throats."

"They pit the lifers against the new kids, the old against the young, the Black against the white. Everything they do is to keep us in our place."

It’s a cynical take, but in the context of the late 70s—with the decline of the American auto industry and the rise of automation—it was incredibly prescient. The film argues that solidarity is the only threat to the status quo, which is why the status quo spends so much energy destroying it.

💡 You might also like: Big Brother 27 Morgan: What Really Happened Behind the Scenes

Richard Pryor’s Greatest Performance

People forget how good of an actor Richard Pryor was. We think of the stand-up, the frantic energy, the "Live on the Sunset Strip" era. But in Blue Collar, he is restrained. He plays Zeke with a simmering, quiet desperation.

There’s a scene where he’s trying to explain to a union rep why he needs a loan or a break, and the look of defeat on his face is devastating. He’s a man who has done everything "right"—he works hard, he has a family—and he still can't afford to fix his daughter's teeth. It’s a performance that should have been nominated for every award under the sun.

Harvey Keitel brings a different kind of intensity. He’s the "family man" who realizes his loyalty has been a lie. Yaphet Kotto is the soul of the movie. He plays Smokey with a weary wisdom. He knows the game is rigged, but he tries to find a way to live with dignity anyway.

The Ending That No One Forgets

Without spoiling the absolute final frames, the conclusion of the blue collar 1978 movie is one of the most famous freeze-frames in cinema history. It’s a visual representation of a fractured brotherhood.

The heist fails not because they got caught by the cops, but because the system absorbed them. It offered them just enough—a promotion here, a threat there—to turn them against one another. It’s a bleak ending. It leaves you feeling angry. And honestly? That’s the point. Schrader didn't want you to leave the theater feeling good; he wanted you to leave feeling like you needed to change something.

📖 Related: The Lil Wayne Tracklist for Tha Carter 3: What Most People Get Wrong

Realism vs. Hollywood Gloss

In 1978, we also had The Deer Hunter and Coming Home. Those were "big" movies about the trauma of Vietnam. But Blue Collar was about the trauma of Monday morning.

It rejected the "poverty porn" tropes. These characters aren't saints. They’re flawed, they make bad decisions, and they’re often mean to the people they love. But the movie never loses sight of why they are that way. It blames the environment, not just the individuals.

Actionable Insights for Modern Viewers

If you’re planning to watch or re-watch this classic, keep these things in mind to get the most out of it:

- Watch the backgrounds. Notice the posters, the dirt on the walls, and the way the factory workers actually move. It’s a time capsule of an industry that basically doesn't exist in the same way anymore.

- Listen to the score. Jack Nitzsche’s soundtrack is gritty and bluesy. It uses "Hard Workin' Man" by Captain Beefheart, which sets the tone perfectly.

- Compare it to "The Irishman" or "The Wolf of Wall Street." Notice how Schrader handles crime differently than Scorsese. In Blue Collar, crime isn't a way to get rich; it's a desperate attempt to stop drowning.

- Research the "Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement" (DRUM). While the movie is fictional, the tensions between Black workers and the UAW in Detroit were very real during this era.

The blue collar 1978 movie remains a staple of American cinema because it refuses to lie to its audience. It doesn't offer a "fix" for the problems it presents. It just holds up a mirror to the assembly line and asks us if we like what we see.

For anyone interested in the history of film or the history of labor, it’s mandatory viewing. It’s raw, it’s violent, and it’s deeply human. It shows that sometimes, the most dangerous thing you can do is realize that you're being played.