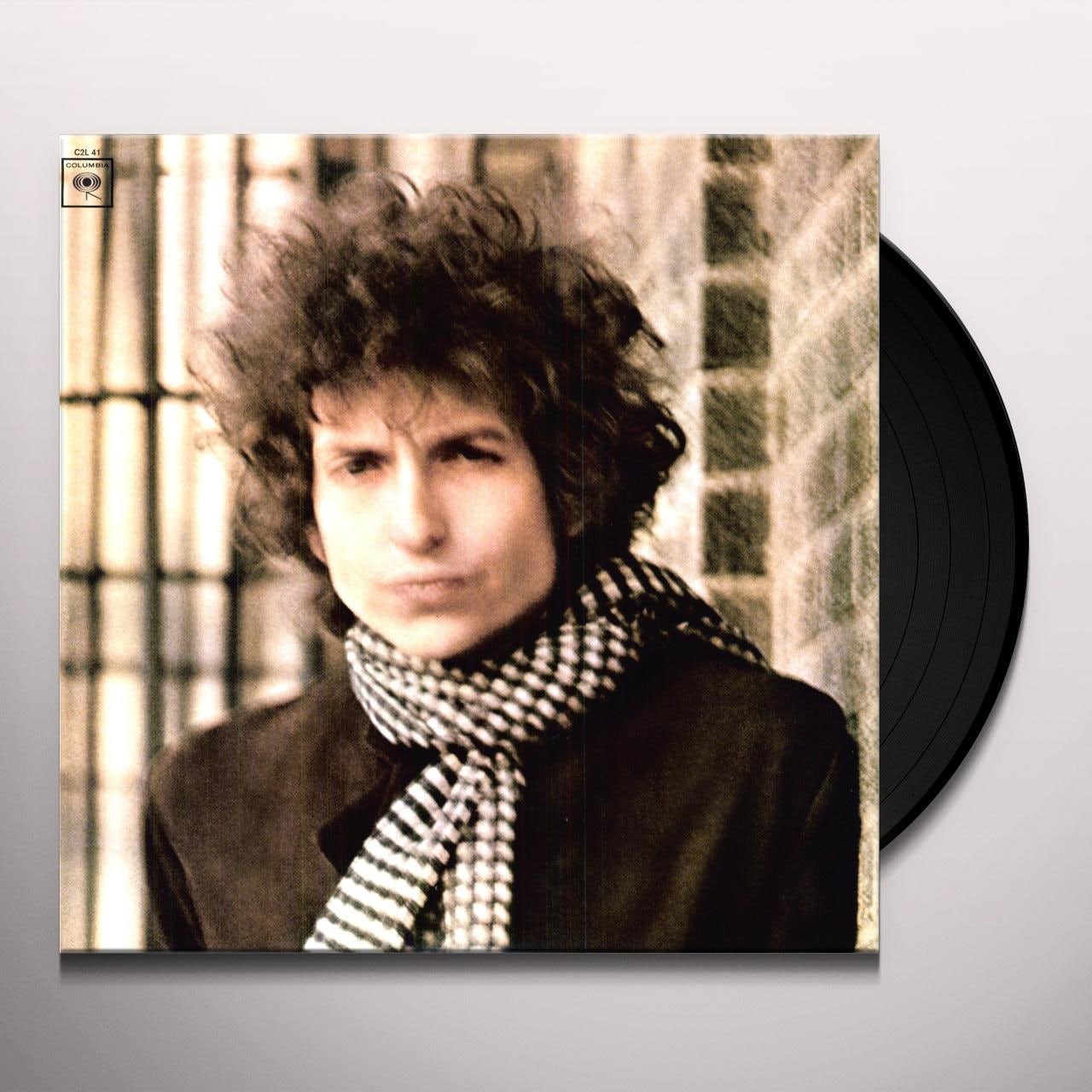

It was 1966. Bob Dylan was vibrating at a frequency nobody else could quite hear yet. He’d already pissed off the folk purists by going electric at Newport, and he’d survived the grueling "judgment" of the UK tour. But he was looking for a sound. Not just any sound, but that "thin, wild mercury sound" he’d later describe to Ron Rosenbaum. He found it in Nashville. He found it on the Blonde on Blonde album by Bob Dylan, a record that basically broke the mold of what a pop LP was allowed to be.

Think about it. In '66, most bands were still trying to figure out how to write a three-minute radio hit. Dylan showed up with a double album. A sprawling, messy, poetic, hilarious, and heartbreaking double album.

The Nashville Gamble

You’ve gotta understand how weird it was for a New York folk-rock icon to head down to Tennessee back then. Most of his peers thought he was crazy. Nashville was the land of "square" country music, session pros in suits, and rigid studio rules. But Dylan’s producer, Bob Johnston, knew exactly what he was doing. He wanted to get Dylan away from the distractions of the city and put him in a room with the "Nashville Cats"—guys like Charlie McCoy, Kenneth Buttrey, and Joe South.

These guys were pros. They played on everything. But they weren't used to Dylan. Honestly, the first sessions were a bit of a culture clash. Dylan would sit at a piano for hours, tinkering with lyrics while the band just sat there, waiting. Sometimes they’d wait until 3:00 AM just to record one take.

Al Kooper, who played organ on the sessions, famously said that the Nashville guys were used to having a chart. Dylan didn't give them charts. He gave them a vibe. He gave them a feeling. And somehow, that friction between Nashville’s precision and Dylan’s chaotic genius created something that sounds like it’s perpetually about to fall apart but never quite does. That’s the magic of the Blonde on Blonde album by Bob Dylan. It’s the sound of a tight band trying to follow a guy who doesn't know where he’s going until he gets there.

💡 You might also like: Why This Is How We Roll FGL Is Still The Song That Defines Modern Country

That "Mercury" Sound Explained

What does "thin, wild mercury sound" actually mean? It’s metallic. It’s bright. It’s loose.

Take a track like "I Want You." It’s bouncy, almost like a nursery rhyme, but there’s this underlying tension in the guitars. Or "Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat," where the blues licks are so biting they practically snarl at you. This isn't the heavy, distorted psych-rock that would come a few years later. It’s cleaner. Sharper.

Then you have "Visions of Johanna." If you haven't sat in a dark room with headphones and listened to this track, you haven't really heard the 1960s. It’s arguably the greatest song ever written. It’s not just a song; it’s a short story, a painting, and a fever dream rolled into seven minutes. The way the bass wanders around Dylan’s voice is just... perfect. It captures that 4:00 AM feeling when the party’s over, the heat is clicking in the pipes, and you’re stuck in your own head.

The Surrealism of the Lyrics

Dylan was reading a lot of Rimbaud and Verlaine. He was also probably taking a lot of... well, let’s just say he wasn't just drinking coffee. The lyrics on the Blonde on Blonde album by Bob Dylan are a massive leap from Highway 61 Revisited. They’re more abstract.

📖 Related: The Real Story Behind I Can Do Bad All by Myself: From Stage to Screen

- "The peddler now speaks to the countess who’s pretending to care for him."

- "Mona Lisa must have had the highway blues, you can tell by the way she smiles."

- "Your debutante just knows what you need, but I know what you want."

He was mixing high art with street slang. He was mocking the "establishment" while simultaneously becoming the biggest thing in it. It’s sarcastic. It’s "kinda" mean in places, but it’s also incredibly vulnerable. "Just Like a Woman" is a masterclass in that weird space between loving someone and being absolutely exhausted by them. Some people call it sexist; others see it as a raw portrait of a crumbling relationship. It’s likely both.

Breaking the 12-Minute Barrier

The album ends with "Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands." This song takes up an entire side of the second vinyl record. Over eleven minutes long. In 1966, that was unheard of.

The story goes that the session musicians thought the song was ending at the three-minute mark, then the five-minute mark, but Dylan just kept going. You can hear the band's energy shift as they realize they’re in for the long haul. Kenny Buttrey’s drumming on this track is legendary. He stays perfectly in the pocket, building the tension stanza by stanza. It was a tribute to his then-wife, Sara Lownds, and it’s one of the few times on the record where Dylan sounds truly, deeply sincere without a hint of his usual irony.

Why It Still Matters Today

Music critics like Greil Marcus and Robert Christgau have spent decades deconstructing this record. Why? Because it’s the blueprint. Before this, albums were mostly a collection of singles and filler. After the Blonde on Blonde album by Bob Dylan, the "album" became an art form in itself.

👉 See also: Love Island UK Who Is Still Together: The Reality of Romance After the Villa

It influenced everyone. You can hear its DNA in The Velvet Underground, in R.E.M., in Beck, and in basically every indie songwriter who’s ever picked up an acoustic guitar and a harmonica. It’s the sound of a man who realized he didn't have to be a "protest singer" or a "folk hero." He could just be an artist.

Common Misconceptions

People often think this was a drug-fueled accident. While there was definitely a "vibe" in the studio, the craftsmanship is undeniable. Dylan was a workaholic. He’d spend hours on a single rhyme. The Nashville session guys were the best in the world. This wasn't a fluke. It was a calculated attempt to capture a specific atmosphere.

Another myth is that it was an immediate universal success. While it did well, plenty of people were still confused. They wanted another "Blowin' in the Wind." Instead, they got "Rainy Day Women #12 & 35" with its marching band brass and "everybody must get stoned" refrain. It was provocative. It was meant to be.

How to Truly Experience Blonde on Blonde

If you’re new to the record, don't just put it on as background music while you’re doing dishes. It won't work. It’s too dense.

- Get the Mono Mix: Many purists argue that the mono mix is the "true" version. The stereo mixes of the 60s were often rushed and sound a bit thin. The mono version has more punch.

- Read the Lyrics: Not while you're listening—that's too distracting. Read them like poetry later. You’ll find internal rhymes you missed.

- Watch 'No Direction Home': Martin Scorsese’s documentary gives incredible context to this specific era of Dylan’s life.

- Listen for the Mistakes: The little cracks in Dylan’s voice, the slight hesitation in a guitar lick—those are the bits that make it human.

The Blonde on Blonde album by Bob Dylan isn't just a relic from the 60s. It’s a living thing. Every time you listen, you hear a different line or a different instrument peeking through the "mercury" haze. It’s an invitation to get lost.

To get the most out of your next listen, pay close attention to the transition between "Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again" and "Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat." The shift from surrealist storytelling to sharp, satirical blues is one of the best 1-2 punches in music history. Also, track down the "Bootleg Series Vol. 12: The Cutting Edge" if you want to hear the raw evolution of these songs—it’s a fascinating look at how much work went into making something sound this effortless.