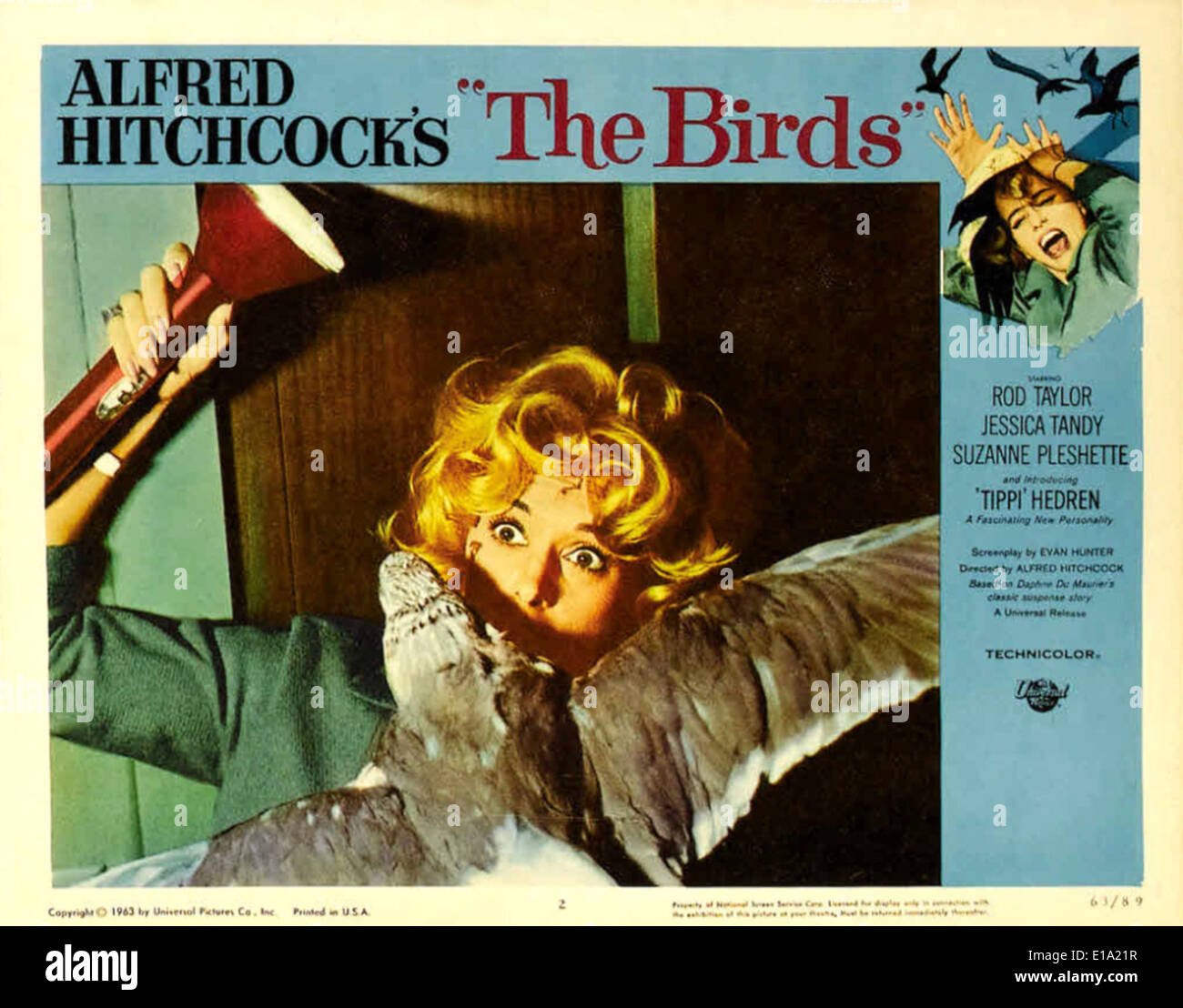

It starts with a simple, cheeky flirtation in a San Francisco pet shop. Tippi Hedren, playing the wealthy socialite Melanie Daniels, meets Rod Taylor’s Mitch Brenner, and the banter is light, almost like a romantic comedy from a different era. But then the air changes. You can feel it. When we talk about The Birds Alfred Hitchcock movie, we’re not just talking about a 1963 thriller; we’re talking about a fundamental shift in how cinema handles the "unknown."

There is no explanation. None.

Most horror movies give you a reason. A curse, a chemical spill, a disgruntled ghost with a grudge. Hitchcock didn’t care about that. He purposefully stripped away the "why," leaving us with the terrifying reality of nature simply turning its back on humanity. It’s visceral. It’s messy. It’s arguably the most frustratingly brilliant thing he ever filmed.

The Technical Nightmare of Bodega Bay

Hitchcock was a perfectionist, often to a fault, and the production of this film was a logistical gauntlet. Before CGI existed, you couldn't just "program" a swarm of crows to gouge someone's eyes out. You had to use real birds, mechanical props, and a whole lot of optical layering.

Ub Iwerks, the legendary animator who helped create Mickey Mouse, was the secret weapon here. He used a process called "sodium vapor" photography—essentially an early, more sophisticated version of a green screen—to matte the birds into the scenes. It’s why the compositions still look hauntingly dense today. If you look closely at the scene where the children run down the hill from the schoolhouse, the layering of the crows is a masterpiece of technical composition.

But it wasn't just technical trickery.

The "real" birds were often quite dangerous. Ray Berwick, the trainer on set, spent months working with crows, gulls, and ravens. They weren't exactly cooperative actors. They bit. They scratched. They were essentially wild animals forced into a high-stress environment.

The Attic Scene and Tippi Hedren

Honestly, what happened to Tippi Hedren during the filming of the famous attic scene is legendary for all the wrong reasons. Hitchcock told her they would use mechanical birds for that sequence. He lied.

👉 See also: Weenie Man Song Lyrics: What Most People Get Wrong

For five days, Hedren was trapped in a room while trainers threw live gulls and ravens at her. One of them nearly took her eye out. By the end of the week, she suffered a complete nervous breakdown. A doctor ordered her to take a week off, to which Hitchcock reportedly complained because it would delay production. It’s a dark chapter in film history that colors how we view the movie today. It wasn't just acting; it was genuine, sustained trauma captured on 35mm film.

Why the Soundscape Replaced the Music

You’ve probably noticed something weird while watching: there is no traditional musical score. No violins, no pounding drums. This was a radical choice by Hitchcock and his frequent collaborator Bernard Herrmann. Instead of a soundtrack, they used the "Remi Gassmann and Oskar Sala" electronic sound designs.

The birds don't just squawk; they screech in a synthesized, unnatural way that hits a specific frequency designed to make the human ear uncomfortable. By removing the comfort of a musical cue—which usually tells an audience how to feel—Hitchcock left the viewers in a vacuum of silence and bird cries. It makes the attacks feel more random. More inevitable.

The Ending That Frustrated Everyone

When the movie premiered, people were actually angry about the ending. We’re used to "The End" appearing over a resolved plot. Instead, we see the Brenner family and Melanie slowly driving away through a landscape covered in thousands of perched birds.

They don't "win." They just escape for a moment.

Hitchcock actually considered an even darker ending where the Golden Gate Bridge was covered in birds, implying the entire world had fallen. He ultimately chose the more quiet, eerie uncertainty of the drive away from Bodega Bay. This ambiguity is exactly why the film stays in your brain. It’s an open wound.

Common Misconceptions About the Plot

- The birds were vengeful: People often try to find a "sin" the characters committed to trigger the attacks. Is it Melanie's vanity? Is it Mitch's mother's jealousy? Hitchcock's notes suggest there is no moral correlation. Nature is just indifferent.

- It’s a "monster" movie: It’s actually closer to a disaster film. The "monster" is the environment itself.

- The effects are dated: While some blue-fringing occurs in the matte shots, the sheer volume of real birds used creates a level of physical reality that modern CGI often lacks.

Survival Lessons from the Screen

If you find yourself analyzing the film from a modern lens, the survival tactics used by the characters are surprisingly grounded. They boarded up windows. They stayed low. They avoided loud noises. In the context of the 1960s, these were also subtle nods to Cold War anxieties—the idea that at any moment, the sky could fall and your home would no longer be a sanctuary.

To truly appreciate The Birds Alfred Hitchcock movie, you have to watch it without looking for a "point." You have to let the atmosphere do the work. It’s a study in tension, pacing, and the breakdown of social order.

Actionable Steps for the Cinephile:

- Watch the "Schoolhouse" sequence with the sound off: Notice how Hitchcock uses "pure cinema"—the editing and the visual buildup—to create dread without a single sound.

- Compare to Daphne du Maurier’s original story: The movie is loosely based on her short story. Reading it provides a much bleaker, more claustrophobic British perspective on the same concept.

- Visit Bodega Bay: Many of the filming locations, including the Tides Restaurant (rebuilt but on the same site) and the Potter Schoolhouse, still exist in Northern California.

- Look for the Hitchcock Cameo: He appears very early, walking two Sealyham Terriers out of the pet shop as Melanie enters. It’s a classic "blink and you'll miss it" moment that sets the tone for his god-like presence over the unfolding chaos.

The film remains a masterclass because it refuses to play by the rules. It denies us a villain to hate and a hero who can save the day with a shotgun. It just leaves us standing in the driveway, looking at the sky, wondering if the crows on the telephone wire are just resting or waiting.