You’ve probably seen the grainy clips of Satchel Paige or Josh Gibson. Those guys were giants. But there’s a specific, weirdly joyful corner of baseball history that usually gets buried under the weight of the "serious" Negro League documentaries. I'm talking about the Bingo Long Traveling All Stars.

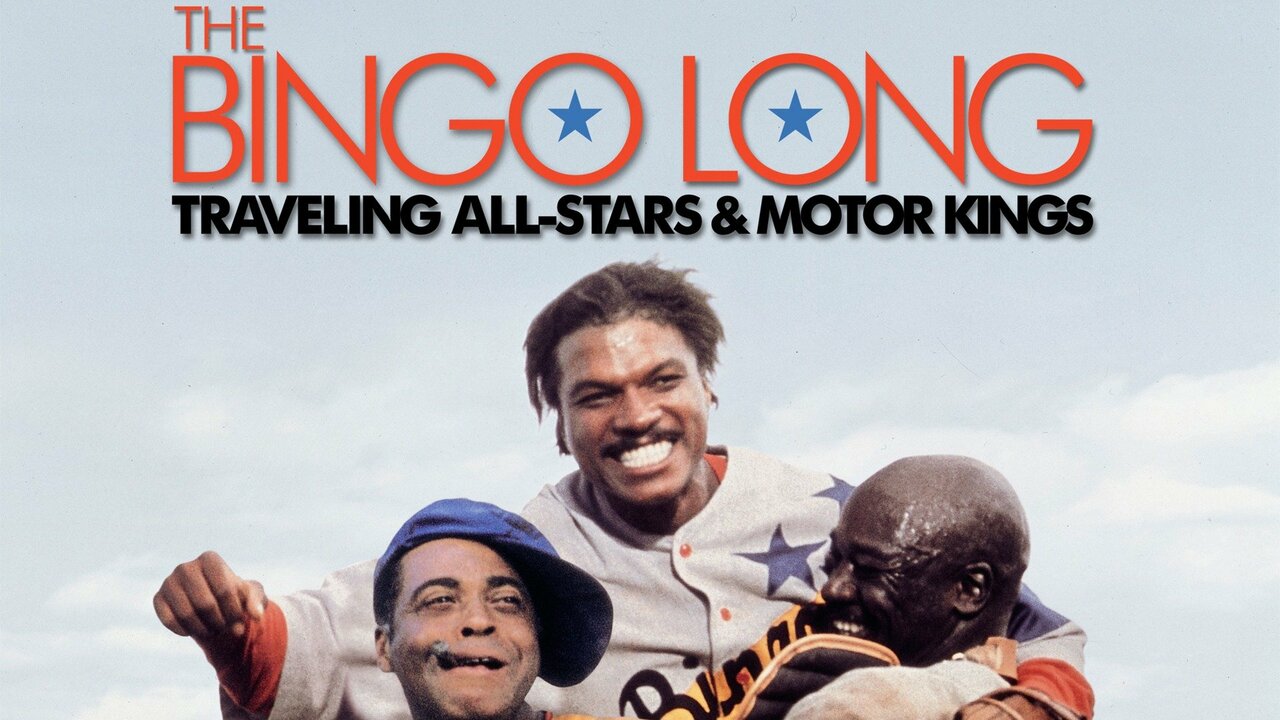

Most people know it as a 1976 movie starring Billy Dee Williams, James Earl Jones, and Richard Pryor. Honestly, it’s one of those films that somehow feels like a party and a history lesson at the exact same time. It’s loosely—and I mean loosely—based on a novel by William Brashler. But the heart of it? That’s real. It’s about the "barnstorming" era, a time when Black ballplayers had to be part athlete, part magician, and part stuntman just to get a paycheck.

The Reality Behind the Bingo Long Traveling All Stars

Let’s get one thing straight: the Negro Leagues weren't just about the stats. They were about survival. In the 1930s, if you were a Black ballplayer, you were basically owned by the league moguls. The movie kicks off with Bingo Long (played by a peak-charisma Billy Dee Williams) getting fed up with Sallison Potter, a team owner who treats his players like property.

Bingo decides to go rogue. He steals the best talent—including a powerhouse catcher named Leon Carter— and hits the road.

This wasn't just movie drama. This was "barnstorming."

👉 See also: Is Heroes and Villains Legit? What You Need to Know Before Buying

Real teams like the Indianapolis Clowns did exactly this. They traveled in beat-up cars through the rural Midwest and South, playing anyone who’d have them. They’d play local white semi-pro teams, factory squads, whoever. To keep the crowds coming (and to keep the local sheriffs from kicking them out of town), they had to "clown." We’re talking about synchronized dance routines on the way to the plate, comedy sketches in the infield, and shadows-ball—where they’d play an entire inning with no actual baseball, just miming the whole thing so fast the crowd couldn't keep up.

Some critics, like Armand White, hated this. They felt the movie made the struggle look "jolly." But if you talk to the actual veterans of those leagues, like the legendary Buck O'Neil, they’ll tell you the humor was a weapon. It was how they stayed sane in a country that didn't want them in the "Big Leagues."

Who were these guys supposed to be?

The movie doesn't hide its inspirations. If you know your baseball history, the characters are basically Easter eggs.

- Bingo Long is a stand-in for Satchel Paige. There’s a scene where Bingo calls his entire outfield into the dugout and proceeds to strike out the side. Satchel actually did that. Frequently.

- Leon Carter (James Earl Jones) is the heavy-hitting catcher. That’s Josh Gibson, the "Black Babe Ruth."

- Charlie Snow (Richard Pryor) is the most tragic and funny part of the whole thing. He’s obsessed with breaking into the majors, so he tries to pass himself off as Cuban ("Carlos Nevada") or Native American ("Chief Takahoma"). It sounds ridiculous, but players actually tried this back then because the "color line" was specifically against Black Americans, not necessarily other ethnicities.

The Motown Connection and 1970s Hollywood

It’s kind of wild that this movie even exists. It was produced by Berry Gordy and Motown Productions. Think about that. The guy who gave us Marvin Gaye and The Supremes decided to make a period-piece baseball movie.

✨ Don't miss: Jack Blocker American Idol Journey: What Most People Get Wrong

It was John Badham’s directorial debut. Yeah, the guy who later did Saturday Night Fever.

The film had a $9 million budget, which was huge for 1976, and it pulled in over $33 million. People loved it. But more importantly, it gave a job to real Negro League veterans. Look closely at the credits. You’ll see names like Samuel "Birmingham Sam" Brison, who actually played for the Birmingham Black Barons. Brison once said that watching the movie was like watching his own life story, which is about as high as praise gets for a "comedy."

Why the Ending Still Sparks Debate

The Bingo Long Traveling All Stars eventually get their big showdown. They play a winner-take-all game against the league stars to prove they deserve to be back in the "official" Negro Leagues. They win, obviously.

But then the scout shows up.

🔗 Read more: Why American Beauty by the Grateful Dead is Still the Gold Standard of Americana

He wants "Esquire" Joe Calloway. Joe is the young, flashy outfielder—the Jackie Robinson/Willie Mays archetype. Bingo gives Joe his blessing to go to the majors, and the movie ends on a bittersweet note. Bingo is planning bigger and crazier stunts to keep his team alive, while Leon Carter looks on, knowing that once the best players leave for the white leagues, the Negro Leagues are dead.

It’s a nuanced take on "integration." Usually, we treat Jackie Robinson’s debut as a purely 100% happy ending. But for the Black communities that owned these teams, it was the end of a massive economic engine. The movie captures that tension perfectly.

How to Experience This History Today

If you actually want to understand the world of the Bingo Long Traveling All Stars, don't just stop at the movie.

- Watch the Documentary: Look for There Was Always Sun Shining Someplace. It’s a 1983 doc narrated by James Earl Jones that features real interviews with the legends.

- Visit Kansas City: The Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in KC is the holy grail. It’s not just jerseys; it’s the stories of the cars, the hotels, and the barnstorming life.

- Read the Book: William Brashler’s novel is grittier than the movie. It’s less "buddy comedy" and more "survival of the fittest."

The legacy of these players isn't just that they were good at baseball. They were entrepreneurs who built something out of nothing when the rest of the world told them to stay in the shadows. Next time you see a highlight reel of a modern player doing something "flashy," just remember: Bingo Long and his crew were doing it in the mud of a Midwestern field 90 years ago, and they were doing it with a smile.

To get the full picture, track down a copy of the 2007 Blu-ray or DVD commentary by John Badham. He breaks down which stunts were real and which were Hollywood fluff, giving you a much deeper appreciation for the actual athleticism required to "clown" while playing professional-level ball.