Light hits a glass of juice. Some of it passes through, but some gets trapped by the molecules inside. It’s a simple observation, right? But this basic interaction is exactly what the Beer Lambert Law describes, and honestly, without it, modern medicine and chemistry would basically fall apart. You’ve probably used it without realizing it if you've ever had a blood test or checked the water quality in a pool. It is the fundamental "bridge" between how much light a substance absorbs and how much of that substance is actually there.

Most people think of it as a dry, dusty equation from a sophomore chemistry textbook. It isn't. It’s a tool for measurement that scales from the tiny vials in a doctor's office to the vast reaches of interstellar space.

The Beer Lambert Law Explained (Simply)

Let’s get the technical stuff out of the way first so we can talk about why it's cool. The Beer Lambert Law is actually a combination of two different observations made by two different guys—August Beer and Johann Heinrich Lambert—roughly a century apart.

Basically, the law tells us that the absorbance of a solution is directly proportional to its concentration and the distance the light travels through it. If you have a darker cup of coffee, it absorbs more light because it’s more concentrated. That's the "Beer" part of the law. If you have a massive vat of that same coffee, it absorbs even more light because the light has a longer path to travel. That’s the "Lambert" part.

When you mash them together, you get a formula that looks like this:

$$A = \varepsilon \cdot c \cdot l$$

In this equation, $A$ is the absorbance (how much light is "stolen" by the sample). The $\varepsilon$ symbol represents the molar absorptivity—think of this as a constant that describes how "greedy" a specific molecule is for light at a specific wavelength. Then you have $c$ for concentration and $l$ for the path length.

It’s elegant. It's precise. But it’s also a bit of a lie under certain conditions, which we’ll get into later.

Why Does This Actually Matter to You?

You might be wondering why a lab technician cares about how "greedy" a molecule is for light. Well, imagine you’re a doctor trying to figure out if a patient has too much glucose in their blood. You can’t just count the molecules by hand. Instead, you use a spectrophotometer.

This machine shines a specific wavelength of light through a blood sample. By measuring how much light comes out the other side, the machine uses the Beer Lambert Law to calculate the exact concentration of glucose. It’s instantaneous. It’s non-destructive. It’s the backbone of clinical diagnostics.

The law shows up in weird places too:

- Environmental Monitoring: Scientists use it to detect pollutants in rivers. If a certain chemical absorbs UV light, they can tell exactly how much factory runoff is in the water just by "looking" at it with a sensor.

- Food Safety: Ever wonder how juice companies keep the color so consistent? They use absorbance to ensure the concentration of pigments is identical in every batch.

- Astronomy: When we look at light passing through the atmosphere of a distant planet, the way that light is absorbed tells us if there’s oxygen, methane, or water vapor there. We are using the Beer Lambert Law across light-years.

The Real-World Nuance: Where the Law Breaks

Here is the thing about science: "laws" usually have fine print. The Beer Lambert Law is no exception. If you try to use it on a super thick, sludgy syrup, it fails.

Why? Because the law assumes that every molecule acts independently. When a solution gets too concentrated—usually above $0.01\text{ M}$—the molecules get too close to each other. They start bumping into one another, changing their charge distribution, and messing with how they absorb light. This is what chemists call "deviations from linearity."

💡 You might also like: Dyson Sphere: Why Science Fiction’s Biggest Idea is Actually Physics

If you're working in a lab and your graph starts to curve instead of staying in a straight line, you've hit a limitation. You’ve basically crowded the dance floor so much that the light can't get a clear "read" on anyone.

There are also physical factors. If your light source isn't "monochromatic" (meaning it's a mix of colors instead of one pure wavelength), the math gets messy. If the sample is cloudy or "turbid," the light scatters like high beams in fog rather than being absorbed. In those cases, the law isn't "broken," but you’re measuring the wrong thing. You’re measuring scattering, not absorbance.

How to Apply This in a Practical Setting

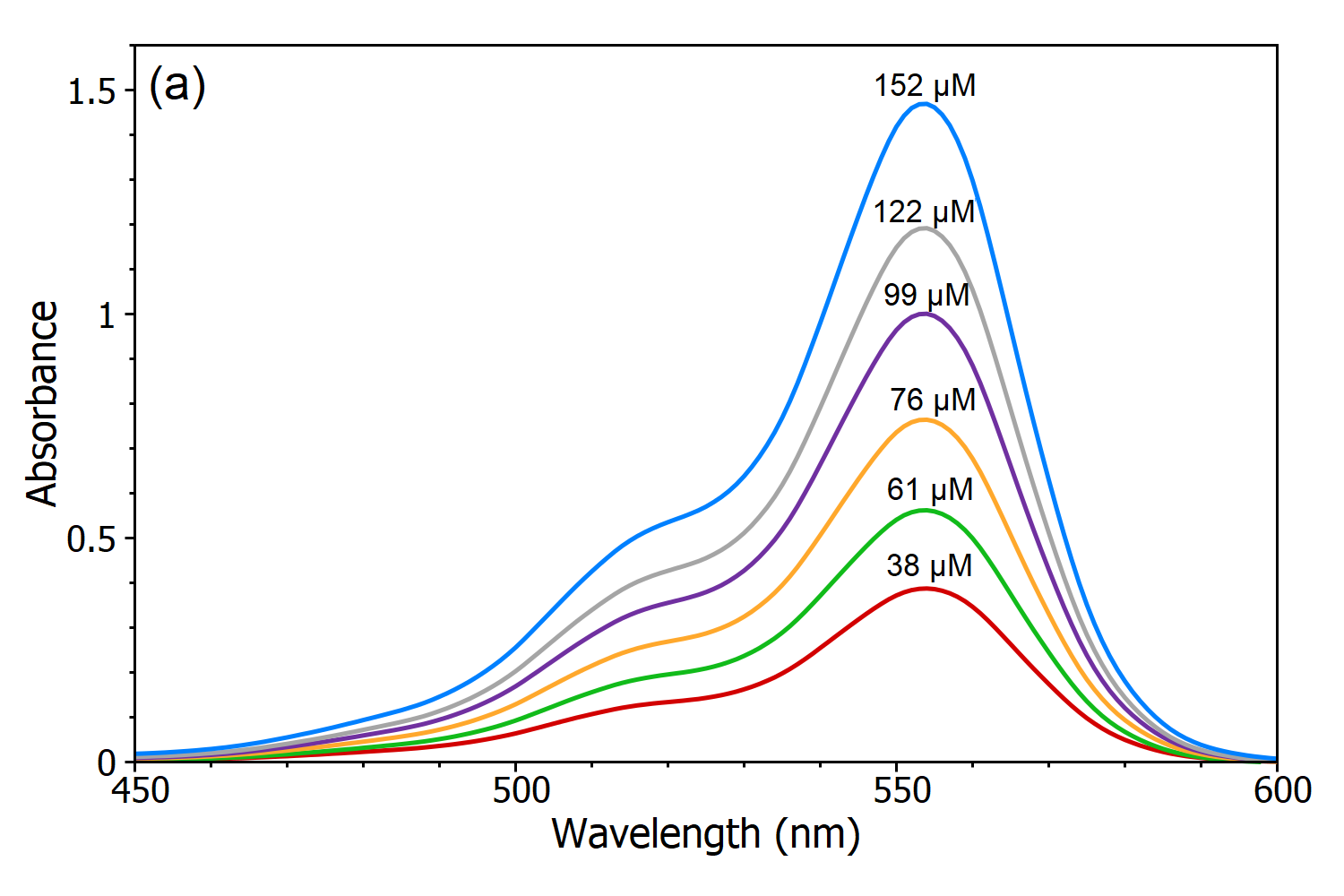

If you’re actually looking to use the Beer Lambert Law for a project or a lab, you need a calibration curve. You don't just jump into the math. You start with "standards"—samples where you already know the concentration.

- Run your standards. Measure the absorbance of five different known concentrations.

- Plot the data. You should see a straight line. If you don't, your solution is too thick and you need to dilute it.

- Find the slope. The slope of that line represents $\varepsilon \cdot l$. Since $l$ (the width of your cuvette) is usually $1\text{ cm}$, the slope basically tells you the absorptivity of your substance.

- Test the unknown. Now, drop in your mystery sample. Look at the absorbance, find that point on your line, and boom—you have your concentration.

It feels like magic, but it’s just accounting. You're just counting photons that didn't make it to the detector.

Common Misconceptions to Avoid

People often mix up transmittance and absorbance. Transmittance is how much light gets through. Absorbance is how much light stays behind.

The tricky part? The relationship isn't linear. If you double the concentration, you don't halve the transmittance. It’s a logarithmic relationship. This is why we prefer to work with absorbance ($A$); it makes the math a lot easier for our human brains to visualize as a straight line.

Another mistake is ignoring the "blank." Every time you use a spectrophotometer, you have to "zero" it using a cuvette filled with just the solvent (like water or alcohol). If you don't, you’re accidentally measuring the absorbance of the glass and the water along with your chemical. It’s like weighing yourself while holding a bowling ball and forgetting to subtract the ball’s weight.

Practical Next Steps for Using the Beer Lambert Law

If you are currently analyzing a sample or studying for an exam, start by verifying your wavelength. Every molecule has a "peak" absorbance ($\lambda_{max}$). If you try to measure at the wrong color of light, your sensitivity will be terrible.

✨ Don't miss: Why an air conditioner system diagram looks more complicated than it actually is

For those in a professional lab setting, always check your linearity range. If your absorbance reading is higher than $1.5$, you are likely in the "danger zone" where the law begins to deviate. Dilute your sample by a factor of $10$, run it again, and multiply your result back. This simple step prevents the most common error in analytical chemistry.

Keep your cuvettes clean. A single fingerprint on the clear side of the glass can absorb as much light as the chemical you're trying to measure. Use lint-free wipes and only touch the frosted sides. Precision in the Beer Lambert Law depends as much on your cleaning habits as it does on your math.